The Democratic Nomination: It Doesn’t Have to be a Long Slog

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— The size of the Democratic field, combined with the party’s proportional allocation of delegates and other factors, raises the possibility of a very long nomination process that may not be decided until the convention.

— However, the voting calendar is so frontloaded that a nominee may emerge relatively early in the process.

— Based on the tentative early primary and caucus calendar, nearly two-thirds of the pledged delegates will be awarded from early February to mid-March.

Frontloaded primary schedule suggests the possibility of an early Democratic knockout

“It gets late early out here.” — Yogi Berra

With a growing field of about 20 candidates, the lion’s share of which should be able to get on to one of the first two debate stages in Miami in late June, Democrats are gearing up for what could be a very crowded, and very lengthy, presidential nomination battle.

For a number of different reasons, it is possible that the nomination season, held from February to early June 2020, will not determine a winner. Obviously, the field is large. There probably won’t be 20 credible candidates on the ballot in Iowa next February, but there still likely will be a lot. Democratic primaries and caucuses award delegates proportionally, with a 15% threshold for winning delegates. Unlike on the GOP side, there are no winner-take-all states. Those kinds of contests can help winnow a field more than proportional ones do, although the 15% delegate hurdle will have the effect of shutting out weaker candidates. Still, one can imagine perhaps three or four leading candidates emerging and trading victories across the country during the first half of next year, with the primary season ending without a clear victor.

If the nomination season ended without someone winning a majority of pledged delegates, the Democratic National Convention could hypothetically go to a second ballot.

The idea of a contested convention is one that political analysts fantasize about every four years. But most us have never seen one in our lifetimes. The last president who was not nominated on the first ballot at his convention was Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt in advance of his initial victory in 1932. In 1936, the Democrats eliminated a provision that the nominee get at least two-thirds of the convention vote, a rule that contributed to many long nomination fights. The last major party presidential nominee who did not win nomination on the first ballot was Democrat Adlai Stevenson in 1952, the first of his two consecutive (and unsuccessful) presidential bids as the Democratic standard-bearer. So by the time the Democrats meet in Milwaukee in July 2020, it will have been 68 years since a major party presidential nominating convention has gone to a second ballot. (The Pew Research Center in 2016 published a great piece about the history of contested conventions.)

In other words, these things have a way of working themselves out. And it may be that the Democratic race could sort itself out quickly, with the party rallying around a probable nominee relatively early in the process. This would be akin to John Kerry’s victory in 2004, when he became the presumptive nominee in early March after knocking out his last remaining major rival, John Edwards (and Kerry was in a commanding position even before then in a race that started in mid-January, as opposed to the February start expected next year). That stands in contrast to 2008 and 2016, long slogs where the eventual winner became clear fairly early (Barack Obama in 2008 and Hillary Clinton in 2016) but where the eventual runner-up stayed in the race for the entirety of the primary season.

One aspect of this year’s calendar that could speed a knockout blow is that the calendar is frontloaded. As the nominating calendar is currently constructed, almost two-thirds of the total number of pledged delegates will be awarded in the first seven weeks of the nominating season, from Feb. 3, 2020 through March 17, 2020.

Before we discuss the current calendar in detail, let’s pause for an important caveat: Not only are the dates of these primaries and caucuses subject to change, but the number of delegates awarded by each state may also change. The calendar is not yet set: For instance, New York is currently scheduled to vote on Feb. 4, 2020, just a day after Iowa. Needless to say, this would totally blow up the calendar, because only four states are allowed by the Democratic Party to vote in February: Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina. But primary expert Josh Putnam, whose Frontloading HQ site is a must-read for those who follow the primary calendar machinations, believes that New York ultimately will vote later than February.

Based on the most recent tallies from the Democratic National Committee, there are 3,768 pledged delegates that will be awarded to the candidates through primaries and caucuses held in all 50 states and the nation’s territories. That means that, as of this moment, the magic number to win the nomination on the first ballot is 1,885 pledged delegates (50% +1 of the total). Again, this specific number is subject to change. Additionally, there currently are 764 “superdelegates,” whose role is different in 2020 than it was in previous Democratic contests. Effectively, the superdelegates only matter if the nomination is not decided on the first ballot. (If you’re curious for more on the superdelegates, see the P.S. at the bottom of this article.)

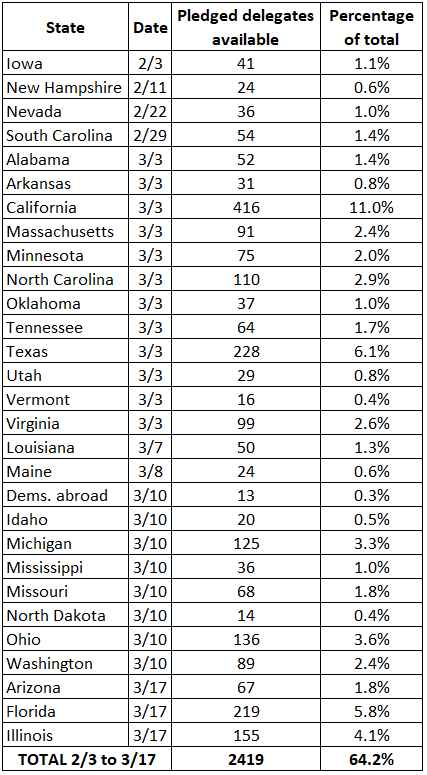

With those caveats out of the way, take a look at Table 1, which shows the tentative Democratic nominating calendar through March 17, 2020.

Table 1: Tentative schedule of Democratic nominating contests, early February through mid-March 2020

Note: This tally excludes superdelegates from the total delegate count; see more on superdelegates at the end of this article. This count may be conservative, as several other states may eventually join this list.

Sources: Schedule information comes courtesy of Frontloading HQ. Delegate counts are from Appendix B of the Call For the 2020 Democratic National Convention, issued by the Democratic Party of the United States and adopted on Aug. 25, 2018.

This is why we led this article with Yogi Berra quote — it gets late early this primary season, with 64% of the pledged delegates slated to be awarded by mid-March. That percentage is subject to change, but it could get even higher if, for instance, states like Colorado and Georgia, neither of which has officially set a date but very well could vote on Super Tuesday, opt to also schedule themselves early in the calendar. New York, as mentioned, is another important state that is not scheduled yet (it voted in April in 2016).

Note that while “Super Tuesday” is March 3, with many states voting including mega-states California and Texas, March 10 and March 17 are mini-Super Tuesdays, with big states Michigan and Ohio currently slated for the former date and Florida and Illinois, along with budding swing state Arizona, scheduled for the latter. About 60% of all the Democratic delegates will be awarded during this two-week stretch. While the February contests are important for setting up the battle to come and winnowing the field, the March contests are the ones with the big delegate prizes.

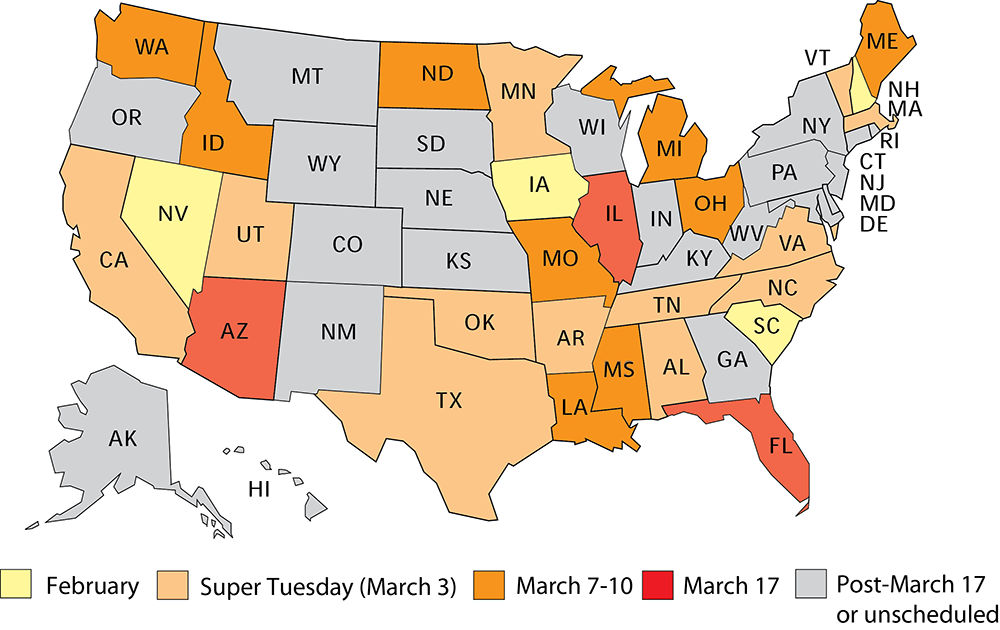

In addition to being frontloaded, the calendar also features demographic and regional diversity. Map 1 visualizes the states in Table 1, colored by their current voting date.

Map 1: Tentative schedule of Democratic nominating contests, early February through mid-March 2020

Every region and size of state is represented in this group of states, although the Great Plains and Mid-Atlantic are largely left out (but Northern Virginia will provide some clues about the feelings of voters in the Acela Corridor). We’ll get an early sense as to which candidates have strength where and with which groups. For instance, Vice President Joe Biden — a current non-candidate who appears to be gearing up to run — has shown some strength with African Americans so far. South Carolina, which has a majority-black electorate, will test that strength; so too will other Southern states on Super Tuesday. Can Biden keep that support if he runs? Will it split many different ways among other candidates, or consolidate in favor of an African-American candidate, perhaps Sens. Kamala Harris (D-CA) or Cory Booker (D-NJ)?

Is there a candidate who becomes a favorite of Hispanic voters? If so, early states like Nevada and Texas might help tell the tale. In 2016, Clinton tended to do better with Democratic self-identifiers, while Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) did better with those who identified as independents. We’ll look for patterns in New Hampshire, where undeclared party voters can easily vote in either party’s primary. It’s almost impossible to see how Sanders is nominated if he doesn’t once again carry New Hampshire, which is basically home turf for him. The stakes are high for Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) there, too, in a state that borders her own.

It doesn’t take an immensely vivid imagination to come up with plausible scenarios where the field gets winnowed fast. Here are a couple of possibilities involving multiple candidates:

— One of the two current polling leaders, Biden or Sanders, sweeps both Iowa and New Hampshire and squeezes the other candidates out of the field. By the same token, if neither of them wins Iowa or New Hampshire, it’s hard to see how either remains viable because they will naturally have been eclipsed by some other candidate. Certainly one would think that, at the very least, all of the white candidates will need to win or show well in either Iowa or New Hampshire (or both) to remain viable, given how historically important and overwhelmingly white both states are. So if someone other than Biden or Sanders performs well in the two leadoff states, they might effectively knock out Biden, Sanders, and many others very early.

— Speaking of, what if Harris wins one of Iowa or New Hampshire, thus proving to African-American voters that she is viable (much like Barack Obama did in 2008 when he won Iowa)? That allows her to win South Carolina and some other Southern states going away, and her home state of California, voting on Super Tuesday, gives her a big win that effectively makes her the presumptive nominee. The same scenario could apply to Booker if he surpasses Harris (and others) for the African-American vote, but he doesn’t have a big home-state prize waiting on March 3 (New Jersey doesn’t vote until June 2).

Remember this, too: Some candidates who seem prominent now won’t even make it to the start of voting. That’s what happened to candidates such as former Govs. Tim Pawlenty (R-MN) and Scott Walker (R-WI) in 2012 and 2016, respectively. The primary process is an unforgiving, and expensive, crucible. That’s why focusing on fundraising is worthwhile: Candidates who build themselves expensive operations need the money to sustain them, and invariably some candidates’ coffers will run dry months before the first votes are cast.

Look, we’ll be honest with you: We don’t have much of a feel at all for who the Democratic nominee is going to be. And we could concoct a dozen different scenarios for a dozen different candidates. We can also envision a world in which no one gets to the requisite number of delegates in the nominating season. It’s just too early to know. All we’re trying to illustrate with this early look at the opening calendar is that it’s possible that this all will be over quickly.

We do think this knockout scenario may depend on which candidate is the one trying to do the knocking out. For instance, many Republicans not named Donald J. Trump probably would have effectively wrapped up the 2016 nomination in early March. But resistance to him remained because he was so anathema to many party leaders, prompting some of his challengers to remain in the race until he landed a knockout blow to Ted Cruz in Indiana in early May. It may be that many of the Democratic candidates would be likelier to bend the knee to a more establishment-friendly early frontrunner, like Biden or Harris, than to Sanders, who still has passionate critics within the Democratic Party. Democrats may generally feel a desire to wrap things up well in advance of the convention so that they can bring the party back together for the general election to run against a president they detest — but if a vocal minority of Democrats don’t like the candidate that the early primaries crown, the fight may go on for months even if the early frontrunner is effectively impossible to catch.

We’ve still got almost 10 months before voting starts. Analyzing it reminds of us of another Yogi-ism: “In baseball, you don’t know nothing.”

We don’t really know exactly what he means by that, but we suspect the observation applies to politics, too.

P.S. How the superdelegates work this time

We didn’t want to digress into a huge discussion of the superdelegates above. But understanding their role, and how their role has changed in 2020, is important when looking at this process.

Overall, there are currently slated to be about 4,530 delegates to the Democratic National Convention. As noted above, the lion’s share of those delegates, about 3,770 of them, are pledged delegates, meaning that their votes will reflect the wishes of the primary or caucus voters in their respective states. The remaining delegates, about 760 of them, are superdelegates, who are delegates because of their roles as elected Democratic officials or other party leaders.

So about five-sixths of the total delegates are awarded through the primaries and caucuses, and about one-sixth are superdelegates officially untethered to the primary and caucus voting process.

In previous cycles, those superdelegates could vote on the first ballot at the convention, meaning that — hypothetically — two candidates could come to the convention without a majority of pledged delegates, and the superdelegates could effectively pick one over the other if they voted as a bloc. The power of the superdelegates enraged Sanders supporters in 2016, even though Clinton would have won the nomination with or without them. The superdelegates actually exist, in part, to protect the party from insurgent candidates like Sanders. The party created them in advance of the 1984 election to give party leaders more of a formal say in the nominating process after two outsider candidates, George McGovern and Jimmy Carter, won Democratic nominations in 1972 and 1976, respectively, and Carter was destabilized by Ted Kennedy’s primary challenge in 1980. They immediately served their intended role: “In 1984, the superdelegates stepped in to provide a majority for Walter Mondale — who had a huge edge in pledged delegates over Gary Hart but not enough to win the nomination — avoiding a potentially bitter and divisive convention that would have fractured the party,” wrote Thomas E. Mann and Norman Ornstein in a 2008 defense of superdelegates.

After the 2016 election, the DNC came to a compromise on superdelegates. Instead of agreeing to fairly extreme options — eliminating them altogether, or keeping them but determining their convention voting loyalties based on the results in whatever state they’re from — the party opted for a more limited change. The superdelegates still exist, but they can only vote on the first ballot if the nomination has been decided by the primaries. Basically, they can vote in the first round as a way of nominating the presumptive nominee by acclaim, but they can’t vote if the first ballot is contested. If a second vote is required, the superdelegates activate and can actually cast consequential votes.

While the change was designed to make the superdelegates a less prominent part of the process, one could see how the reform could actually make the superdelegates very prominent. If the convention goes to a second ballot, the superdelegates might effectively decide the nominee. This could have potentially explosive consequences, particularly if the superdelegates side with — just as an example — an establishment candidate like Biden over an insurgent like Sanders.

Democrats, of course, hope that none of this matters. But just keep the superdelegates in mind when assessing the race: If it’s truly close, they could be decisive. At which point, the party officials who backed these changes may find themselves pondering yet another Yogi classic: “We made too many wrong mistakes.”

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.