Lessons from History: House Incumbents from the Non-Presidential Party Rarely Lose Reelection in Midterms

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— The non-presidential party often picks up House seats in midterms, and as a part of it, that party’s incumbents rarely lose in midterms.

— Over 13 general election midterms held during the last half-century, just an average of 3 non-presidential party House members have lost per midterm.

— Redistricting as well as special election winners losing their subsequent general election inflate that total. Otherwise, a variety of other factors—including scandal, strong challengers, political circumstances, and more—contributed to these relatively rare losses.

Opposition party House members in midterms

It is possible that in a little more than a week’s time, there will be a federal government shutdown. A March 14 deadline for Congress to keep the government open through a continuing resolution looms, and while Republicans have a narrow majority in the House—218-214 at the moment, with two Republican vacancies in Florida that will be filled on April 1, and a new Democratic vacancy following the sudden death of Rep. Sylvester Turner (D, TX-18) on Wednesday morning—they very well may not be able to produce the level of party unity required to pass the CR on their own.

Democrats, meanwhile, may have to decide whether they want to provide majority Republicans with votes to keep the government open. As Politico’s Rachael Bade reported earlier this week, Democrats are wondering whether they should, particularly as House Republicans have rebuffed their efforts to use the CR to assert congressional authority in the face of Donald Trump and Elon Musk’s “DOGE” cuts.

If there is a shutdown, there will be a blame game, too. At a basic level, Republicans would appear to be responsible, given that they control both chambers of Congress and the White House, even though Republicans struggle to maintain party unity in the House. That said, if there is a CR that gets nearly-unanimous support from House Republicans and no support from House Democrats, or if the CR is blocked from passage in the Senate by a Democratic filibuster, perhaps the Republicans could pin the shutdown on the Democrats.

It’s worth remembering that we are in March of an odd-numbered year—the next federal election is more than a year and a half away. We doubt a shutdown now would have any bearing on the midterm, regardless of which party the public would blame more for it.

Beyond that, even if House Democrats were to take a public relations hit from a shutdown—again, this is all hypothetical—there is a longer-term trend that very well could insulate them in their next election: Opposition party incumbents rarely lose in midterms.

“Opposition party” is defined here as the party that does not hold the White House (it does not necessarily mean the party in the minority in the House). We frequently note that the president’s party often struggles in midterm elections, particularly in the House: Since the Civil War, the president’s party has lost ground in the House in 38 of 41 midterms, with the only exceptions coming in 1934, 1998, and 2002. It stands to reason that if the opposition party often gains seats in midterms, then the opposition party’s incumbents rarely lose in those elections.

This is definitely the case. Going back over the last half century of midterms—13 elections, starting in 1974—only a total of 36 opposition party incumbents lost in the general election to a member of the president’s party. That’s an average of only about 3 per election cycle. This comes despite not every one of these elections being a clear wave against the president’s party in the House.

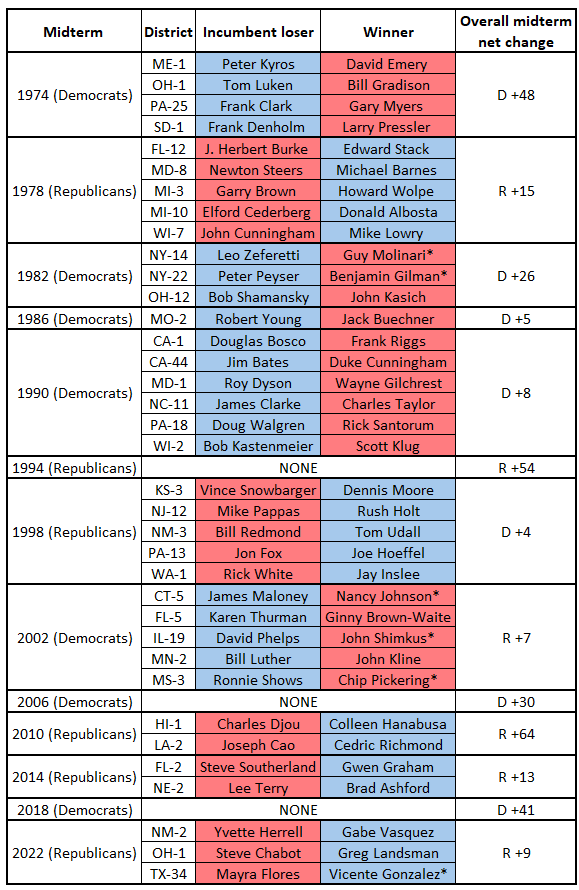

Table 1 shows those who did lose. Note that the largest number of opposition party incumbents to lose in any recent midterm general election was 6 Democrats in 1990, a year that the Almanac of American Politics volume covering that cycle characterized as an “anti-incumbent” year. Still, that’s not a very high number. In 3 of the 13 elections, no opposition party incumbents lost at all: No Republican incumbents lost during the 1994 Republican wave, and no Democratic incumbents lost in the 2006 and 2018 Democratic waves (the Democrats did not lose any previously-held seats at all in 2006—in the two other years, the opposition party did lose some open seats). We also included the net change in the midterm overall in the final column of Table 1.

Table 1: Midterm non-presidential party incumbent House general election losers, 1974-2022

Notes: Net party change calculated by author, and it compares the net change from what happened in the previous election; tallies might be slightly different than other sources because independents were apportioned to the major parties based on whom they caucused with. *Winning candidate was an incumbent from the presidential party. Only includes incumbents who lost to a member of the president’s party in midterm general elections.

Source: I used research I conducted for my history of recent House elections, The Long Red Thread (2021), to create this table, along with past editions of the Almanac of American Politics as well as Wikipedia and Open Secrets

The scant total of opposition party incumbent losses would likely be even smaller were it not for redistricting, which played a role in at least a quarter of the losses. Additionally, there are a handful of other losses that involved a new incumbent who won in a special election during the cycle losing in the next regular election. Let’s look at those first (a part of a group we are dubbing the “flukes”), and then the redistricting losses, followed by all the others.

Reversing a fluke (7)

(Luken 1974, Cunningham 1978, Shamansky 1982, Redmond 1998, Djou 2010, Cao 2010, Flores 2022)

Close to 20% of all of the out party incumbent losses across these midterms are what we are describing as “reversing a fluke.” This means that something odd happened in the immediately previous election that did not end up lasting in the next midterm election.

Five of these midterm out-party losing candidates—Luken, Cunningham, Redmond, Djou, and Flores—won special elections for vacant seats in advance of the midterm, but then they could not hold those seats in the regular election. And there were sometimes strange circumstances that allowed for these members to be elected in the first place, such as a Green Party candidate getting 17% of the vote in a 1997 special in NM-3 to replace the departed Bill Richardson (D), who was becoming ambassador to the United Nations and would later serve as governor of New Mexico. That allowed Bill Redmond (R) to win with just 43% of the vote, but he would go on to lose by 10 points in November 1998 to future senator Tom Udall (D). In a special election in HI-1, two Democrats split the vote in an all-party special election, allowing Charles Djou (R) to win the seat. He would lose it in November 2010, a rare bright spot for Democrats amidst a Republican mega-wave nationally. The other Republican House incumbent to lose that November was Joseph Cao in a deeply Democratic New Orleans district, LA-2. He defeated scandal-plagued William “cold cash” Jefferson (D) in 2008 (the election was actually held in December 2008, not concurrent with the November presidential election, which likely aided Cao). Two years later, Cao was soundly defeated.

Flores losing in 2022 also has a redistricting component, because she won a 2022 special election and then lost to Rep. Vicente Gonzalez (D, TX-34) in a bluer version of TX-34 in November. That district would subsequently vote for Donald Trump in 2024, swinging about 20 points from 2020, as Gonzalez again beat Flores in a close race. So a Republican winning TX-34 in 2026 or sometime in the future certainly would be no fluke. But unlike those in the next category, and in the context of 2022, Flores was not really a victim of redistricting, as she won the vacant old seat as a non-incumbent, and Democrats did not strongly contest the seat in the June 2022 special election.

In 1980, Bob Shamansky (D) upset a long-serving, weak Republican incumbent in a Columbus-area district, OH-12, a rare Democratic bright spot amidst the Reagan sweep. Two years later, he would lose to future governor and presidential candidate John Kasich (R). Redistricting arguably played a role in that Shamansky alienated state Democratic leaders, meaning that they did not go to bat for him in post-1980 redistricting, but the topline, Republican-leaning partisanship of the district did not change much under the new 1982 lines.

The cases of Shamansky and Flores also show that some results defy simple categorization, but we thought they belonged in this group as opposed to the next one, dealing specifically with incumbents who lost more clearly as a result of redistricting.

Possible 2026 parallel: If Democrats were to win a huge upset in a House special sometime this cycle—maybe the Trump +20ish NY-21 that Elise Stefanik (R) would eventually leave behind when/if she is confirmed as ambassador to the United Nations—they might then have a really hard time holding it in November 2026.

Redistricting factor (9)

(Zeferetti 1982, Peyser 1982, Maloney 2002, Thurman 2002, Phelps 2002, Luther 2002, Shows 2002, Herrell 2022, Chabot 2022)

New district lines played a role in another quarter of these incumbent defeats, including arguably all five of the Democratic incumbent losses in 2002—one of the rare instances in American history where the presidential party actually gained House seats in the midterm.

In 4 of those 5 losses (Karen Thurman in FL-5, David Phelps in IL-19, Bill Luther in MN-2, and Ronnie Shows in MS-3), the Democrat in question pretty clearly got a worse district than the one they had previously held, which contributed to their losses, and 2 of them (Phelps and Shows) lost to Republican incumbents in incumbent vs. incumbent matchups. However, James Maloney (D) in CT-5 actually was able to run in a slightly bluer district than the one he held prior to redistricting, as it had voted for Al Gore by 9 points in the 2000 presidential race after his previous district had voted for Gore by 7 points. But the bigger problem for him is that he had to face fellow incumbent Nancy Johnson (R), a well-regarded candidate, in a member vs. member race in November, and Maloney had preexisting weaknesses on account of campaign finance problems. (Johnson would later lose to now-Sen. Chris Murphy in the 2006 Democratic wave.)

Democrats Leo Zeferetti and Peter Peyser lost to Republican incumbents in strongly Republican districts in 1982 as part of several incumbent-on-incumbent clashes necessitated by New York losing 5 seats in the 1980 census reapportionment.

Much more recently, Steve Chabot (R, OH-1) and Yvette Herrell (R, NM-2) saw redistricting transform their districts from ones that voted for Donald Trump in 2020 to ones that had voted for Joe Biden, which definitely contributed to their losses.

Possible 2026 parallel: Ohio is going to have a new congressional map for 2026, and it could make life harder for up to 3 Democrats: Reps. Marcy Kaptur (OH-9), Emilia Sykes (OH-13) and Greg Landsman (OH-1), who defeated Chabot in 2022. If one or more were to lose in redder versions of their current districts, they would fit in this category.

All others (20)

(All other incumbent losses not otherwise noted in the previous two categories)

The other opposition party incumbents who lost in midterms had a variety of different causes for their defeats, and there often were more reasons than just one. The two Republicans who lost in 2014, Lee Terry (NE-2) and Steve Southerland (FL-2), both made mistakes that undermined their reelection bids and also had reasonably strong challengers. A number of other opposition party losers were longer-serving members who faced talented challengers making a compelling case for change and/or who focused on a particular local issue that hurt the incumbent—that basic description applies to some of the 1974, 1978, and 1990 losers, and some of these successful challengers went on to higher offices, such as future Sens. Rick Santorum (R-PA), and Larry Pressler (R-SD).

An overreach on Bill Clinton’s impeachment likely contributed to some Republican losses in the 1998 midterm, another rare instance of the president’s party gaining House seats in a midterm. We wrote about the 1998 midterm in depth in a previous issue. If a number of incumbent Democrats were to lose in 2026, perhaps there would be a similar kind of dynamic—not an impeachment of Trump in all likelihood, but some other issue in which Republicans were able to put Democrats on the spot despite Republicans controlling the government (that is a very tall order, made harder by the fact that Republicans controlled Congress in 1998 while Democrats don’t control anything right now, and Bill Clinton’s approval rating was very high).

Being on the wrong side of district-level political changes also likely contributed to some of these—that appeared to be a culprit for the lone 1986 Democratic incumbent loser, Robert Young (MO-2). District-level changes may have also contributed to the loss by J. Herbert Burke, a South Florida Republican, in 1978. But his landslide loss was surely driven more by scandal—he was arrested outside a nude club and eventually pled guilty to misdemeanors stemming from the incident. Burke’s embarrassing spectacle later served as an inspiration for the Carl Hiaasen novel Strip Tease as well as a widely-panned 1996 movie of the same name starring Demi Moore as well as Burt Reynolds as a fictional congressman based on Burke. Scandal touched on a few of the other opposition party members who lost, although not as notoriously as Burke.

Possible 2026 parallel: Rep. Henry Cuellar (D, TX-28) has seen his district swing wildly toward Republicans as he faces a trial later this year on corruption charges (although one wonders if he might get an Eric Adams-style reprieve from the Trump administration). Additionally, Cuellar could face a potentially strong Republican challenger after facing a weak one in 2024: Tano Tijerina, a top Webb County official who recently switched parties, is considering challenging Cuellar. If Cuellar were to make it to November 2026 as the Democratic candidate and lose that election, there would be a number of reasons for why he might have lost that would have historical parallels amongst this aforementioned group.

Conclusion

In all likelihood, at least one incumbent Democratic House member will lose next November, although there have been recent elections where the opposition party hasn’t seen any of its incumbents lose a general election. If one or more does, there very well could be special circumstances that contribute to that person losing that would be similar to the circumstances described above. Overall, it would be historically unusual if more than a few incumbent House Democrats lost in the 2026 general election.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.