Redistricting in America, Part One: Gerrymandering Potency Raises the Stakes for the 2020s

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— While partisan gerrymandering is nothing new in American politics, it has become easier to find examples of states where gerrymanders are consistently effective and harder to find examples of “dummymanders” — gerrymanders that fail.

— Republicans control the drawing of more districts in this round of decennial redistricting than Democrats do.

— Democrats arguably would be better off if no states had bipartisan/independent redistricting commissions.

Redistricting in the 2020s: An overview

In 1981, Indiana Republicans enacted a partisan gerrymander of the Hoosier State designed to help Republicans net several seats. “Even the Democrats here concede that the newly drawn congressional district lines are a political masterpiece and that they face a much tougher task now in retaining their one-vote majority in Indiana’s congressional delegation,” reported the Washington Post.

But that following year, Republicans failed to make significant inroads in Indiana — the delegation went from 6-5 Democratic to a 5-5 split after the state lost a district because of reapportionment. By the end of the decade, Democrats held an 8-2 edge in Indiana, despite the Republican gerrymander.

Three decades after the creation of that failed GOP gerrymander in Indiana, a new Republican-controlled state government sought to create a 7-2 Republican map. Republicans held a 6-3 edge at the time after netting two seats in the 2010 Republican wave. The new map worked. While then-Rep. Joe Donnelly (D, IN-2) ended up running for U.S. Senate — and he surprisingly won — now-Rep. Jackie Walorski (R, IN-2) narrowly won a more Republican version of Donnelly’s old seat. Indiana elected seven Republicans and two Democrats to the House for the entire decade.

To the extent that partisan gerrymandering is a problem in American democracy — and not everyone believes that it is a problem — it’s not necessarily because the intent of would-be gerrymanderers has become more nefarious, but rather because their handiwork is arguably more effective now than it’s been in the past.

It’s not hard to find examples from the last half century, like Indiana Republicans in the 1980s, who tried and failed to gerrymander. One study of 1970s congressional redistricting found that of seven attempts at partisan gerrymanders, only one was a clear success. But it’s harder to find such examples recently, as some of the factors that once insulated House members from gerrymandering threats — such as ticket-splitting and the power of incumbency — have waned in, respectively, prevalence and strength.

Some partisan gerrymanders from the 2010s — such as the one mentioned in Indiana and other Republican-drawn maps in Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, as well as a Democratic gerrymander of Maryland — behaved exactly as designed the entire last decade, though there were some close calls for the gerrymandering party in some of these states.

North Carolina Republicans drew two immensely efficient gerrymanders before Democratic-controlled state courts forced a third remap that cut the GOP edge from 10-3 to 8-5 in the 2020 election.

An Illinois Democratic gerrymander was designed to produce, ideally, a 13-5 Democratic delegation. It did, eventually, in 2018, but Democrats ended up winning two suburban/exurban seats in the Chicagoland orbit that were designed to be won by Republicans, while two downstate districts Democrats hoped to win remained in Republican hands.

A brutal Republican gerrymander of Pennsylvania worked as expected for three cycles, producing a lopsided 13-5 Republican edge in an otherwise competitive state, but the gerrymander began to show signs of strain when now-Rep. Conor Lamb (D, PA-17) won a special election in early 2018, and then the Democratic-controlled state Supreme Court imposed a new map that produced a 9-9 delegation in both 2018 and 2020.

Democrats eked out a 7-7 split on a Michigan map designed to be 9-5 Republican, largely because of GOP suburban problems that helped now-Reps. Elissa Slotkin (D, MI-8) and Haley Stevens (D, MI-11) win in the last two elections.

The bottom line on redistricting last decade is this: The maps did not always perform the way they were designed to for the entire decade, and courts also intervened to take the edge off of some Republican gerrymanders. But no state backfired on the line-drawing party as much as, for instance, Indiana did in the 1980s, which underscores the likelihood that modern gerrymanders are more foolproof than ones from several decades ago (computing advances might have helped the effectiveness of modern gerrymanders, too).

A few decades ago, Democrats often exerted more power over redistricting in more places than Republicans, frustrating the GOP. Back then, Republicans sometimes pressed for the kinds of reforms that Democrats, now on the wrong side of redistricting wars, want today. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush proposed federal legislation to outlaw partisan gerrymandering, but nothing ever came of it in the then-Democratic-controlled Congress.

The Democrats’ signature “For the People Act” would mandate the creation of independent redistricting commissions in all states. That bill passed the House but has stalled in the Senate, and it appears very unlikely to pass so long as the filibuster exists.

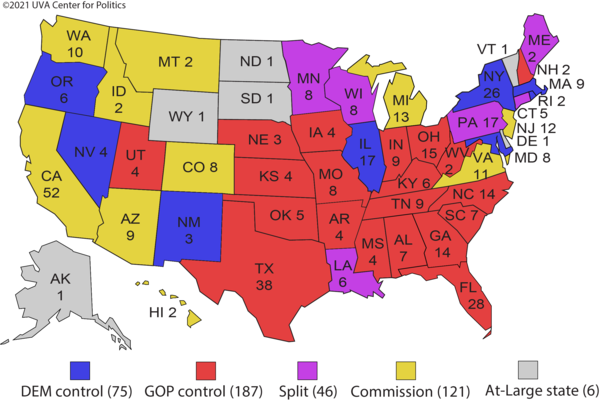

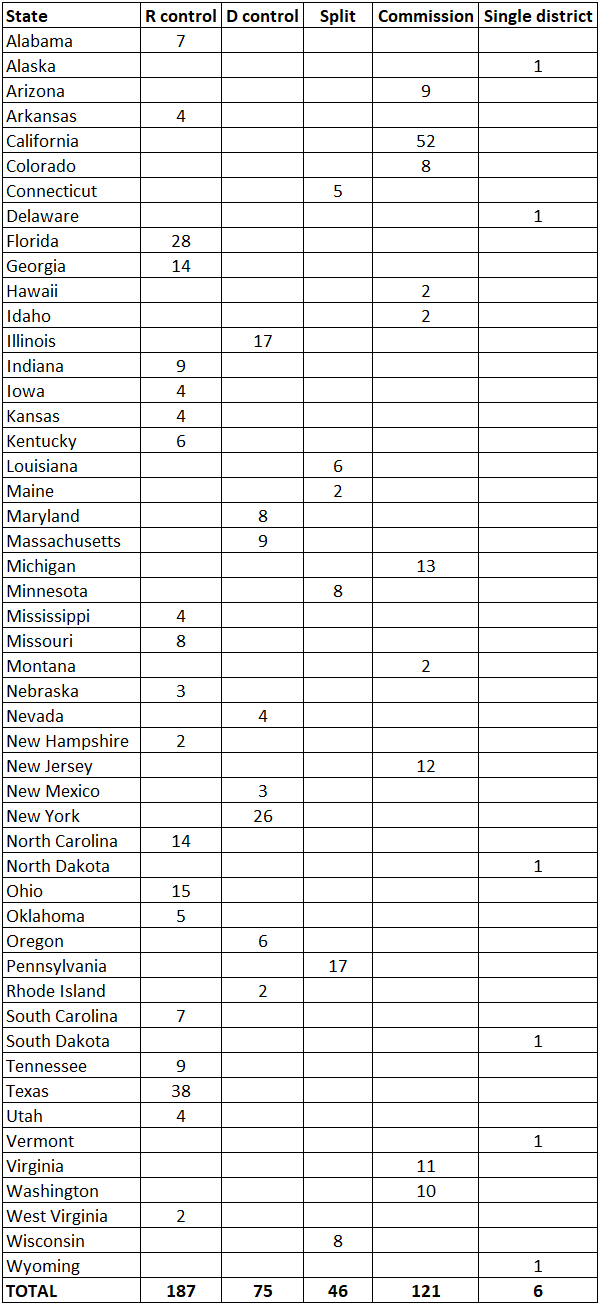

Table 1 and Map 1 illustrate the Republican redistricting edge at the start of this decade’s process. Republicans control the drawing of 187 of the 435 seats, or 43% of all the districts, while Democrats have control over just 75 districts, 17% of the districts. Meanwhile, 46 districts (11%) are in states with divided government while 121 (28%) are in states with nonpartisan/independent commissions. The remaining six districts (1%) are in states with just a single, at-large congressional district.

Map 1 and Table 1: Post-2020 redistricting control/method by state

Note: Connecticut and Maine are listed as split-party control because while Democrats control state government in both states, they lack the two-thirds legislative majorities required to completely control the process. We made some judgment calls on other states that we would be happy to explain if you’re curious — just send us an email at goodpolitics@virginia.edu.

Source: All About Redistricting, Crystal Ball research

The number of states that use independent/bipartisan commissions has increased in recent years: a little more than a quarter of the total seats in the House are in states that use some sort of commission. Colorado, Michigan, and Virginia are all decent-sized states that have implemented some form of commission system in recent years.

Specifically, there are 10 states that use a commission to draw the lines: Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Michigan, Montana, New Jersey, Virginia, and Washington. If those commissions did not exist, and redistricting power was instead given to the state legislature with the possibility of a gubernatorial veto, Democrats would have the power to draw the maps in six of these 10 states (California, Colorado, Hawaii, New Jersey, Virginia, and Washington), Republicans would have the power in three (Arizona, Idaho, and Montana), and there would be divided government control in Michigan (Democrats hold the governorship, Republicans hold the state legislature).

Instead of Republicans holding a 187-75 edge, their advantage would be a more modest 200-170 under this scenario, with the remaining 65 districts either in one-district states or in ones with divided government.

So in some states, Democrats may be, or are, kicking themselves for backing redistricting commissions. Both parties supported a 2018 Colorado ballot issue that created an independent redistricting commission for congressional maps. Had it not passed, Democrats now would have gerrymandering power in the Centennial State and drawn themselves a better map than a draft the commission released a few weeks ago, which likely will result in a 5-3 Democratic delegation but could split 4-4 in a strong Republican year. “We’re (expletive) idiots,” said one anonymous state lawmaker, as quoted by the Colorado Sun.

Still, Democrats have sometimes benefited from commissions. Voters in California, the state that still has by far the largest House delegation despite losing a seat in the 2020 reapportionment, created a commission system prior to the 2010 redistricting round, and the commission produced a map where Democrats thrived over the course of the decade, netting eight seats to move from a 34-19 edge to 42-11 (and that’s after Republicans clawed back four seats in 2020). A ProPublica investigation from 2011 found that Democrats figured out ways to surreptitiously influence the commission. Regardless, we doubt a Democratic gerrymander would have performed as well for Democrats as the actual map in the nation’s largest state did over the course of the 2010s.

Additionally, there can be and perhaps will be constraints on redistricting in some of the states where one party holds sway on paper. For instance, Oregon Democrats gave Republicans a greater role in redistricting in exchange for Republicans cutting down on obstruction tactics regarding other legislative matters.

In four big states where Republicans hold sway — Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, and Texas — court action, or the fear of court action, could take some edge off GOP mapmaking. State courts weakened Republican gerrymanders in Florida and North Carolina last decade, although there are some questions about whether those courts would do so again as currently constituted (and while North Carolina has a Democratic governor, Roy Cooper, he has no say in redistricting matters). Ohio has an untested new process that places some constraints on gerrymandering and incentivizes minority party buy-in, although Republicans could get around that by imposing a map that lasts for just four years, instead of the customary 10 (although the courts are a wild card there, too). And even in Texas, Democrats have been able to trim Republican gerrymandering to some extent through racial redistricting lawsuits, although Republicans still hold an impressive 23-13 edge there (it was 25-11 before 2018), and they will hope to expand on that advantage as the megastate adds two additional seats. One big difference between this cycle and the last one, though, is the U.S Supreme Court’s Shelby County v. Holder decision from 2013, which threw out the federal preclearance formula for congressional redistricting and other voting-related matters in states and other jurisdictions with a history of discriminatory voting laws (a list that included Texas). Still, it’s reasonable to expect lawsuits in Texas and elsewhere. The U.S. Supreme Court, in 2019’s Rucho v. Common Cause, once again declined to place constraints on partisan redistricting.

Some of the most important questions in redistricting involve smaller states. Republicans may specifically target single Democratic-held districts in Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee, and Democrats may do the same in Maryland and New Mexico. How aggressive the majority party in each state is will help determine who wins the House majority in 2022 — and whether the intensity of partisan gerrymandering is increasing.

In the coming weeks, we’ll be writing about redistricting by region, and we’ll touch on every state that has more than one district (44 of the 50 states). As we write about redistricting, we’re going to keep in mind a recent quote from Roy Barnes, the former Democratic governor of Georgia who pushed a not-so-successful gerrymander in the 2002 redistricting cycle: “There are no saints in redistricting. Everyone is a sinner.” That Republicans are better-positioned to commit more unrepentant sins in redistricting than Democrats are is the general takeaway at the starting gate.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.