For Biden, a Stunning Super Tuesday

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik and J. Miles Coleman

Former VP sweeps South and moves North; Sanders has to rally in Midwest to avoid being swamped

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

-- That Joe Biden swept the South was not that big of a surprise; that he won states outside of it was.

-- The overall delegate math is unclear and may very well have ended up close on Super Tuesday, but Bernie Sanders needed to come out of it with a significant lead. He didn’t do that.

-- With Biden likely to win more big victories in the South, Sanders has to win some of the big upcoming Midwestern states -- Michigan, Illinois, and Ohio -- to keep pace.

The stunning Biden turnaround

Joe Biden’s challenge on Super Tuesday was to build on his victory in South Carolina and defend the other Southern states from incursions by Bernie Sanders. Not only did he accomplish that, but Biden was William Tecumseh Sherman in reverse -- using the South as a springboard to move North in force.

We were not particularly surprised that Biden won every southern state, but Biden winning Maine, Massachusetts, and Minnesota was stunning.

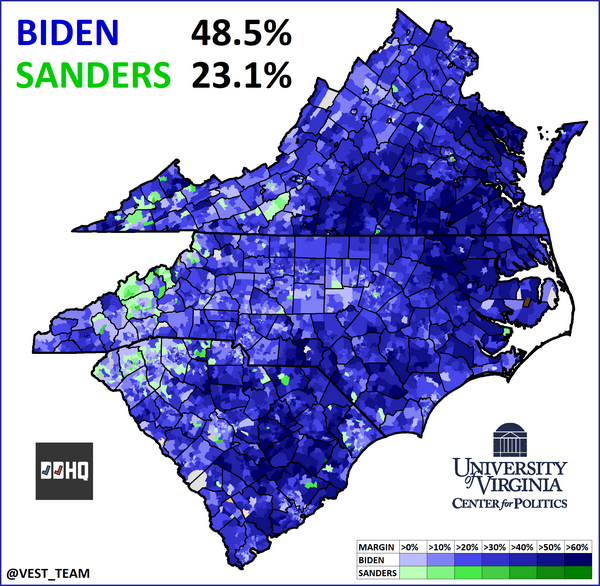

Two of the first states reporting last night were North Carolina and Virginia. As soon as a critical mass of votes from those states were tallied, it was clear that they were very much an extension of South Carolina (Map 1).

Map 1: 2020 Democratic primary in Virginia and the Carolinas

In most counties, Biden was claiming outright majorities. Conventional wisdom suggested that Biden would perform well with African Americans -- which he did -- but there was little positive news for Sanders in the suburbs or Appalachian parts of the states, regions where he had shown a modicum of strength in 2016. Virginia set the tone for the night, in that Biden’s performance in the suburbs carried over to places in other regions -- like the Twin Cities in Minnesota, a state which was, to a large extent, in question going into the night. Likewise, Sanders' weakness in rural parts of Virginia were indicative of other regions, like eastern Oklahoma, where he performed much worse than his 2016 showing.

It is also very surprising that Biden may very well come out of Super Tuesday with more delegates than Sanders, but that is a story yet to be written. As of this writing (Wednesday afternoon), our delegate count with Decision Desk HQ shows Biden up 501-438 over Sanders (that takes into account the February contests as well as Super Tuesday). There are still many delegates yet to allocate, and the lion’s share comes from California -- which Sanders won (along with Colorado, Utah, and his home state of Vermont). So Sanders might catch up -- but, remember, our expectation (shared by other analysts) was that Sanders would come out of Super Tuesday with some sort of substantial delegate lead.

In that sense, Biden really overperformed.

The dramatic and sharp shifts in the race were driven in no small part by the signals that Democratic leaders have been sending to Democratic base voters since Nevada about what they believe are the perils of nominating Sanders. Biden’s smashing win in South Carolina restored faith in his presumed electability, and the twin dropouts and endorsements by Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar allowed Biden to keep riding the wave (surely Klobuchar’s backing was especially helpful in her home state of Minnesota).

Sanders’ supporters will cry foul, saying the “establishment” is taking the nomination from them. But party leaders can only make arguments at this point of the primary season: It’s up to voters as to whether they want to heed those arguments. Clearly, many did, particularly Election Day voters. This showed up in Virginia, a state that does not have much meaningful early/absentee voting and where Biden rolled up a 30-point victory. Biden likely would have won states like North Carolina and Texas by more had a significant chunk of the vote not already been cast before his surge.

Sanders, meanwhile, arguably wasted the 10 days following his victory in Nevada. It is quite possible that there is nothing Sanders could have done to reassure Democratic leaders (and voters) who were concerned about his ability to win a general election, but Sanders did not do anything, at least publicly, to extend an olive branch to his detractors.

Instead, he reminded skeptical Democrats of what worries them about Sanders: He once again defended certain aspects of Fidel Castro’s regime in Cuba; he said that his vice presidential nominee would have to support Medicare for All, a proposal that strikes even some Democrats as politically and practically unpalatable; he declined to attend the Selma civil rights march commemoration in Alabama on Sunday, making him the only major Democratic presidential candidate who did not show up; he continued to rail against the “Democratic establishment.”

None of these things are that important on their own. Put together, they didn’t help Sanders change any minds among Democratic leaders and voters already predisposed to oppose him. Nor has Sanders’ steadfastness helped him generate higher turnout that benefits him, specifically among younger voters. Instead, it appears that the spikes in turnout are centered in affluent, highly-educated suburban places where Sanders doesn’t have that much appeal (see friend of the Crystal Ball Niles Francis’ map of Virginia turnout as an illustration -- compared to 2008, turnout was significantly higher in blue-trending and suburban Northern Virginia than in less densely-populated areas).

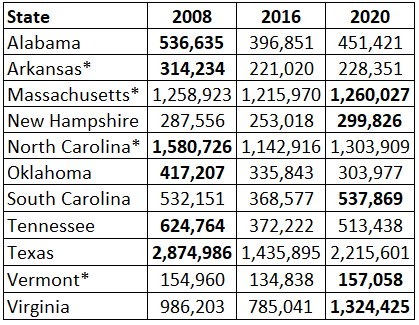

Turnout overall is definitely up when compared to 2016, but not always when compared to 2008, the blockbuster Barack Obama-Hillary Clinton primary. Table 1 compares primary turnout over the last three contested years; remember that population size naturally grows almost everywhere, so even matching 2008 doesn’t necessarily mean turnout was better. We don’t know if these turnout spikes are really predictive of anything for the fall, but obviously any party wants to engage more voters as opposed to less. We excluded California here because so many votes remain to be counted as well as states that held caucuses this year or in past years, and some of these states are not fully reported yet (noted with an *).

Table 1: Recent Democratic primary turnout

Notes: * indicates states with incomplete vote counts. We excluded states that have held caucuses in one or more of these years, and also California, where the vote count is substantially incomplete. Year in bold is highest turnout of the three elections. Data is as of 4 p.m. Wednesday afternoon.

Sources: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections for 2008, 2016, and 2020 New Hampshire and South Carolina; Decision Desk HQ for 2020 Super Tuesday states

Remember, too, that Republicans had a contested primary as well in 2016; the absence of such a race is likely boosting Democratic turnout to some degree. Donald Trump, meanwhile, romped in all of his primary contests yesterday, getting vote shares in the high 80s even in a Trump-skeptical GOP state like Utah.

The path ahead

After Nevada, Democratic leaders had a short window to work to stop Sanders. It appears that they took advantage of that window. Sanders is not quite stopped, but the advantage has passed to Biden now.

The reason why we highlight Biden’s victories in the North is that they represent a positive sign for him after his horrible start to the nominating season in Iowa (the Midwest) and New Hampshire (the Northeast). Many of the major big states that have yet to vote lie in these regions: Michigan votes next week, Illinois and Ohio the week after, and then New York and Pennsylvania on April 28. Given what we saw last night, one has to like Biden’s chances in these states, at least at the moment. Biden also seems very likely to win the big Southern states Florida (March 17) and Georgia (March 24) comfortably.

There is always the possibility the race may change again. Certainly Biden is going to be under renewed scrutiny, and his campaign performances have been shaky at best (last night he seemed to mix up his sister and his wife during the start of his victory speech, for instance).

But Sanders also has not expanded his own base, and it’s clearer than ever now that at least some of his support in 2016 was simply a function of being the alternative to Hillary Clinton. Matched up with Biden more directly now, it’s unclear whether he’ll be able to match his 2016 achievements. Michigan, coming up Tuesday, is a big test: Sanders’ big upset there helped him prolong his campaign four years ago. What happens now? Sanders also needs to win Washington state; he has performed well in the West, but this is another state (like Minnesota) that moved from a caucus to a primary this year, and Clinton actually beat Sanders in Washington four years ago in a “beauty contest” primary (Sanders dominated the caucus, which awarded delegates).

Biden will win Mississippi in a landslide Tuesday and probably Missouri, too, albeit by a smaller margin: The state has some similarities to Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Tennessee, all places where Biden won by double digits on Tuesday night.

Michael Bloomberg flopped, winning only American Samoa. He dropped out Wednesday morning and endorsed Biden; presumably, Biden will benefit from his exit more than Sanders, as seemed to be the case following the exits of Buttigieg and Klobuchar.

Elizabeth Warren finished third in her home state of Massachusetts, and she didn’t even finish second anywhere else. As of this writing, she was reassessing her situation -- possibly a prelude to getting out of the race. If she dropped, that might help Sanders on the margins, but their supporters do not perfectly overlap. She is backed by a fair number of highly-educated suburbanites who might break more toward Biden -- particularly as he continues to bask in the glow of Tuesday's victories.

Biden has plenty of liabilities, liabilities that likely prevented what now appears to be a Democratic consolidation around him prior to now. He isn’t going to excite many; he has a long voting history that Democrats (and Trump) can and will use against him; members of his family have likely benefited financially from sharing a last name with him; he is often mistake-prone on the stump; and he shows his age, more so than other candidates on both sides who are also predominantly old. But with Sanders rising and nowhere else to go, both voters and party elites rallied around the former vice president, who can credibly run as a steady hand contrasted to the president.

A week and a half ago, the hour was growing late for Sanders’ opponents. Amazingly, the hour is now growing late for Sanders. He needs to win in the Midwest over the next couple of weeks to prevent Biden from building a pledged delegate lead that Sanders will be hard-pressed to surpass.

P.S. The Montana Senate race

Wednesday afternoon, Jonathan Martin of the New York Times reported that Gov. Steve Bullock (D-MT) appears likely to enter the Montana Senate race against Sen. Steve Daines (R-MT). If this happens, we will move our rating there from Likely Republican to Leans Republican. Montana is often more competitive down the ballot than it is for president, and Bullock is the only Democrat who could conceivably push Daines for reelection. But the incumbent would still start as a favorite. One has to imagine that Biden's resuscitation as a leading presidential candidate has something to do with this: National Democrats, rightly or wrongly, certainly believe that Biden is more of an asset to down-ballot Democrats than Sanders.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.