Election 2019 Mega-Preview: Political Conformity Seeks Further Confirmation

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik and J. Miles Coleman

Looking ahead to next week’s elections in Kentucky, Mississippi, New Jersey, and Virginia; House ratings changes.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Nationalized politics points to a Democratic edge in next week’s Virginia state legislative elections, and a Republican advantage in the Kentucky and Mississippi gubernatorial races.

— Yet, there remains uncertainty in all of those key contests as local factors test the durability of larger partisan trends.

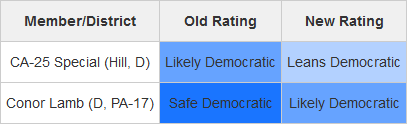

— Unrelated to next week’s action, we have two House rating changes to announce, both benefiting Republicans. The pending CA-25 special election moves from Likely Democratic to Leans Democratic following Rep. Katie Hill’s (D) decision to resign, and Rep. Conor Lamb (D, PA-17) moves from Safe Democratic to Likely Democratic.

— However, what appears to be a pending court-ordered congressional remap in North Carolina should benefit Democrats.

Table 1: Crystal Ball House ratings changes

Will next week’s elections break the mold?

As Americans head to the polls next week, there are three major prizes at stake. Republicans currently control all three of these prizes: the governorships in Kentucky and Mississippi and majority control of the Virginia General Assembly, composed of the state House of Delegates and the state Senate.

In an era of political nationalization that is bleeding down the ballot even to state-level races, the best bet in all three states would be to go with partisanship. And that’s where we’re leaning: Our ratings for the gubernatorial races in Kentucky and Mississippi remain Leans Republican and, while we don’t issue ratings for specific state legislative chambers and races, our sense is that the Democrats are better-positioned than Republicans to win both the Virginia House of Delegates and (especially) the Virginia Senate.

A look at the basic political trajectory of all three states suggests why.

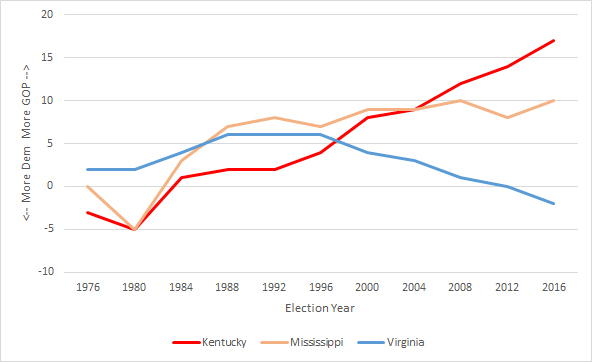

Figure 1 shows how all three states have voted in the two-party presidential vote compared to the nation from 1976 through 2016. Basically, a positive number means a state was more Republican compared to the nation, while a negative number means a state was more Democratic. An upward-slanting line means a state is becoming more Republican compared to the nation over time; a downward-slanting one means it’s getting more Democratic (for more explanation of this calculation, which we call presidential deviation, see this Crystal Ball piece from earlier this year).

Figure 1: Presidential trends in KY, MS, and VA, 1976-2016

As Figure 1 makes clear, Kentucky has become markedly more Republican over the past 40 years, trending that way even before Donald Trump’s takeover of the GOP pushed it — and many of its neighbors in Greater Appalachia — even further toward the Republicans.

Mississippi hasn’t trended much one way or the other in recent years, but it has been persistently more Republican than the nation for the last three decades.

Finally, Virginia started this four-decade period as the only state that was a part of the old 11-state Confederacy to vote for Gerald Ford (R) in his 1976 battle against Southerner Jimmy Carter, who was the last Democrat to win decisively in the South (Kentucky isn’t technically part of that group, but Mississippi is). Four decades later, Virginia stood apart again, this time as the only Southern state to vote for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump.

The political direction of these three parts of the Greater South shows a region moving in different directions.

Virginia, driven by the growth of demographic groups favorable to the Democrats, is moving away from the Republicans. That change is coming specifically in many affluent, highly-educated suburban areas that used to vote Republican but now do not in large part because of a negative reaction to Trump’s candidacy and presidency. This has been enough to offset a Republican trend in the more rural, less diverse, and less populated western part of the state. Virginia’s overall trend toward the Democrats is in some ways decoupling it from its traditional political association with the conservative South and realigning it with the states of the Mid-Atlantic, such as Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey (which has elections of its own next week, as described below). To be clear, Virginia is not as Democratic as those states are, but its direction may be similar.

Mississippi, which has the highest share of African-American voters of any state in the nation, nonetheless has more white voters, and the former group’s Democratic voting is not enough to offset the latter group’s Republicanism.

Kentucky retained much of its Democratic lean at the statewide level until recently; Democrats only lost control of the state’s House of Representatives in 2016, and Matt Bevin (R) in 2015 became only the fourth Republican elected governor since the Great Depression. Next week, he will try to become the first Republican to ever be reelected to the governorship, although Kentucky governors only became eligible to run for a second consecutive term after a 1992 state constitutional amendment.

The signs of political nationalization are all around us. In 2016, every state with a Senate race voted for the same party for president and for Senate. Less than 10% of all 435 U.S. House seats voted for a different party for House in 2018 and president in 2016, continuing a trend of ticket-conformity more similar to a century ago than to a decade or two ago.

The 2018 midterm featured a highly nationalized environment where Democrats largely made their gains in districts that had voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 or had voted only marginally for Donald Trump; Republicans, meanwhile, unseated three of the five Senate Democrats who held strong Trump states. Democrats picked up seven state legislative chambers, all of which were in states that voted for Clinton; six of the seven Democratic gubernatorial pickups came in states that either voted for Clinton or came very close to doing so.

In other words, the overall trends suggest a lesson for handicappers: lean toward the direction to which nationalized partisanship points unless there’s a compelling reason not to.

In the cases of Kentucky, Mississippi, and Virginia, we don’t think the evidence to pick against partisanship is strong enough, which is why we’re leaning the way we are in all three states (toward Republicans in the Kentucky and Mississippi gubernatorial contests, and toward Democrats in the Virginia state legislative races).

But that doesn’t mean there isn’t some chance that nationalization will stall in one or more of these states. Of the three states, we think an upset would be least surprising in Kentucky, where Bevin is hugging the president tightly as a way to make up for his weak approval rating.

What follows is an assessment of the Virginia state legislative races, followed by analysis of Kentucky and Mississippi. We are also featuring some commentary from a couple of young, talented analysts this week: Chaz Nuttycombe has been rating the Virginia races, and we include some of his thoughts in our Virginia section. We also asked Ben Kestenbaum, who contributes to the New Jersey Globe, to provide an assessment of the New Jersey General Assembly race, where Democrats already hold a strong majority.

The final major race of 2019 will be in Louisiana on Saturday, Nov. 16, when Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) will try to overcome the partisan lean of his state to win a second term. We’ll have more to say about that race closer to the election.

High stakes in the Old Dominion

If Democrats net the necessary two seats in each chamber of the Virginia General Assembly to take full control of state government in Richmond, it is not hyperbolic to say that Virginia will have its most liberal state government ever. However, that statement isn’t as profound as it sounds, because Virginia’s governing history is deeply conservative, whether when it was dominated by postbellum conservative Democrats or, more recently, strongly influenced by conservative Republicans who have either ruled the roost outright in Richmond or held enough power to stymie liberal preferences.

While Democrats have won four of the state’s last five gubernatorial races, none of those Democratic governors enjoyed a free hand in the legislature, as Republicans have controlled the state’s House of Delegates since the 1999 election, a victory achieved during the governorship of Jim Gilmore (R) and thus prior to that of Mark Warner, the Democrat elected in 2001 to begin the Democrats’ current stretch of gubernatorial success. Tim Kaine (D) followed Warner in 2005 and later joined him in the U.S. Senate, with Terry McAuliffe (D) elected in 2013 and Ralph Northam (D) in 2017. The only GOP governor in this recent stretch has been Bob McDonnell, who was elected in 2009. Democrats have held the state Senate for part of the past two decades, but a Democratic governor confronted by an at least partially Republican legislature has been the most common alignment in recent history.

Republican power in the state House has been sustained in part by a favorable set of district lines, drawn by the party in advance of the 2011 elections (the Democrats who then controlled the state Senate drew that chamber’s map, but Republicans forged a 20-20 tie despite it that year). Still, the Democratic trend in the state’s big metro areas — Northern Virginia, Greater Richmond, and Hampton Roads — allowed Democrats to come quite literally within a coin flip of a 50-50 House of Delegates split in 2017, but a Republican won a tied race on the basis of a random drawing following the election. In advance of this year’s election, Democrats benefited from a court order that redrew some of the state’s House of Delegates districts.

The Senate, meanwhile, was last contested in 2015; Republican Glen Sturtevant held the then-open 10th District in the Richmond area by less than three points, which allowed the GOP to maintain the majority, 21-19; had Democrats won that seat, they would have forged a 20-20 split in which then-Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam (D) would have broken ties (although the tiebreaking power of the lieutenant governor in the Virginia Senate is not all-powerful; it doesn’t apply to the budget, for instance). Current Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax (D) retains that potential tiebreaking power: Despite being accused by two different women of sexual assault, Fairfax remains in office. So too does Northam, the Democratic governor who was rocked by the early February revelation of his medical school yearbook page, which featured pictures of two men, one in blackface and another in a Ku Klux Klan hood.

The recent political shifts in that decisive 2015 district, SD-10, help show the overall trend in the places that matter most in 2019.

In 2013 and 2014, SD-10 was an almost perfect bellwether for the state. McAuliffe (D) won it by four points while winning statewide by 2.5 points, and a year later, Sen. Mark Warner (D) carried it by two points while winning by a point statewide. But by 2016, Clinton was winning it by a dozen points while she won statewide by five, and all three members of the Democratic statewide ticket carried the district by double digits in 2017, running ahead of their statewide margins (these figures are from the Virginia Public Access Project).

Overall, the most important races in Virginia are being contested on turf that is, on paper, favorable to Democrats. Following the House remap, Clinton carried 56 of the state’s 100 districts, and Republicans currently hold seven of those districts. Democrats don’t hold any Trump-won seats. In the Senate, where districts have not been redrawn, Republicans hold four Clinton-won seats, while Democrats don’t hold any Trump-won seats. In fact, none of the 19 Democratic-held Senate seats (out of 40 total) appear flippable for Republicans.

As noted above, we asked Virginia analyst Chaz Nuttycombe to provide some thoughts about the House and Senate picture. His commentary follows in the block quote below:

The state Senate is nearly certain to flip Democratic because Democrats technically only need to win one seat in order to have Lt. Gov. Fairfax break ties, and Democrats are currently positioned to net two to four seats in the chamber.

The House of Delegates is slightly less likely, but Democrats are favored regardless. This is mostly because of the redistricting that altered about a quarter of the state’s House districts, from Richmond to Hampton Roads, to unpack African-American voters in gerrymandered districts. Had Republicans been able to keep the map they drew in 2011, which Democrats at the time voted for overwhelmingly, Democrats would be looking at a 50/50 shot at control in the House of Delegates at best.

In the state Senate, there are just seven competitive races, all held by Republicans: one in Northern Virginia, three in Greater Richmond, two in Virginia Beach, and one in Central Virginia. The open SD-13 in Northern Virginia looks likely to flip to Democrats, as does SD-10 in Richmond, and Democrats might appear better-positioned to scratch out wins in SD-7 in Virginia Beach as well as SD-12 in Richmond. Republicans remain favored to hold the remaining competitive districts (SD-8, SD-11, and SD-17).

In the House of Delegates, nearly a third of the seats in the chamber are competitive to at least some degree, and there are more competitive GOP-held seats than Democratic-held ones. Democrats look likely to hold all of the 49 seats they control in the chamber at the moment: the seats they’re in most danger of losing are HD-10 (Northern Virginia), HD-73 (Greater Richmond), and HD-85 (Virginia Beach), the latter two of which are open races, as their incumbent Democrats decided to run for state Senate instead. Due to redistricting, Democrats look at least slightly favored to flip HD-76, HD-91, and HD-94, all of which are in the Hampton Roads area. Additionally, there are close races in Republican-controlled districts HD-27, HD-28, HD-40, HD-66, HD-83, and HD-100. If Democrats win two of these races, they’re almost certainly winning a majority.

My current ratings are available here. Additionally, you can follow me on Twitter to keep up with results as they come in on election night, and if you are watching the results as they come in from the Virginia Public Access Project, I recommend checking out this spreadsheet which shows key precincts in key races in both chambers.

Christopher Newport University’s Wason Center for Public Policy recently released a combined poll of the four crucial Senate elections that Chaz cited above: SD-7, SD-10, SD-12, and SD-13. That poll found Democrats leading a combined generic ballot by 14 points.

Our own sources concur with the overall assessment that the Senate is likelier to flip than the House, but there is some disagreement as to whether Democrats will win the House or not, as the Democrats may lose an incumbent or two who won in 2017 and/or the two competitive open seats they are defending (HD-73 and HD-85). However, one Democratic source involved in the House campaign, who is usually a pessimist for his own side, told us he is “straining to find bad news” and that, if anything, the late break in the campaign could be toward the Democrats.

If that is what happens, it would mirror what happened in Virginia two years ago. Remember that Northam’s race against former Republican National Committee Chairman Ed Gillespie seemed very competitive at the end, and even in internal Democratic tracking the weekend before the election, Northam was only up by about 3-4 points. But then he won by nine points. It may be that the same anti-Trump animus that drove that result could drive this one, too. That brings us back to that word we keep repeating: nationalization.

The hope for Republicans is that they will still benefit from a lower-turnout environment — there are no statewide races this year, and turnout is always lowest in Virginia in these off-off-year state legislative races — and a more reliable voter base. But a problem for Republicans is that the affluent, highly-educated white voters who turn out at high rates and are crucial to the outcome in many key districts are much more open to voting Democratic than they were before Trump.

When the Democratic statewide executive apparatus blew up over scandal earlier this year — recall that in addition to Northam and Fairfax’s problems, state Attorney General Mark Herring (D) also admitted to a collegiate brush with blackface, too — Republicans hoped that the Democratic leaders’ problems would help them hold the state legislature. But in today’s scandal-soaked political culture, the travails of the state officials seem to have taken a back seat to other issues in the campaign, including — most notably — perceptions of the president. If Democrats do in fact win both legislative chambers, Trump’s occupancy of the White House, and the negative reaction to him among many voters in the key districts, will be the single biggest reason why.

However, it may be premature to just assume the Democrats survived the Northam scandal — we ought to wait for the results first. If Republicans manage to hold one or both chambers, it may have something to do with unfavorable Democratic turnout, and lower-than-expected black turnout could be a component of that. If that does happen, it’s possible that residual bad feelings over Northam, specifically among black voters, may yet contribute to a Democratic disappointment. We are not betting on that being a decisive factor, but it’s something worth filing away in the event of an upset.

Kentucky: Bevin banks on Bluegrass Republicanism

Gov. Matt Bevin (R-KY) may be, as some polls suggest, the least popular governor in the country. Despite his lagging approval numbers, Bevin finds himself locked in a competitive reelection campaign with state Attorney General Andy Beshear (D), the son of the two-term Democratic governor that preceded Bevin, Steve Beshear.

During his tenure, Bevin, an anti-establishment conservative known for his gruff demeanor, teamed up with a Republican legislature to pass a litany of GOP priorities, from abortion restrictions to enacting a right-to-work law. Still, Bevin has run into opposition in his red state, most notably from teachers’ unions, which has given Democrats an opening. In response, Bevin and Republicans are trying to nationalize the race, using the Democrats’ pursuit of impeachment as a way to remind wavering Trump voters to stick with a GOP governor they may not like, as the New York Times’ Jonathan Martin explained earlier this week.

Bevin entered the general election campaign after an underwhelming primary performance. Though the GOP field included four candidates, state Rep. Robert Goforth (R) was Bevin’s main challenger. Goforth, who cited the governor’s combative style as his motivation for running, largely self-funded his campaign, and took 39%, holding Bevin to just 52%. Though Goforth’s strength was generally localized to his home region, in the southeastern 5th Congressional District, it exposed underlying intraparty discontent with the governor. That happens to be a part of the state where the Democratic brand is most on life support, so it’ll be interesting to see if this protest vote against Bevin manifests itself in the general election.

On Tuesday night, two of the most telling counties in the state will be Elliott and Campbell. Geographically, both are in the northern region of the state but are trending in sharply different directions.

Though a small rural county, Elliott’s trajectory has been emblematic of broader trends in Appalachia. Established in 1869, it began voting in presidential elections in 1872. For the next 140 years, it voted exclusively for Democrats, often by overwhelming margins. In 2008, it was President Obama’s best county in the commonwealth, giving him 61%; by 2012, though, Obama held Elliott with just a 49% plurality. In 2016, Elliott County’s long Democratic streak abruptly ended, as it gave Donald Trump 70%.

State Rep. Rocky Adkins (D), who was edged out in the primary, hails from Elliott County and has barnstrormed the area with Beshear. In 2015, Bevin lost the county by 17% — if Beshear can significantly expand on this margin, it would be an indication that Adkins was an effective surrogate in eastern Kentucky.

While Elliott County is known for its historic loyalty to Democrats, given trends in the region, Beshear could still compete without it — and he may have to. This scenario played out next door, in West Virginia, last year: in his close reelection, Sen. Joe Manchin (D) leaned on the more populous counties in his state, while losing a few rural counties where he routinely overperformed earlier in his career.

Aside from in its two largest cities, Louisville and Lexington, and their surrounding areas, Kentucky’s largest contingent of “Hillary Clinton Republicans” may be in its three northernmost counties: Campbell, Kenton, and Boone. The trio is located just south of Hamilton County, OH and are becoming increasingly influenced by the blue movement of Cincinnati. Of the three, the easternmost county, Campbell, seems likeliest to vote Democratic next week.

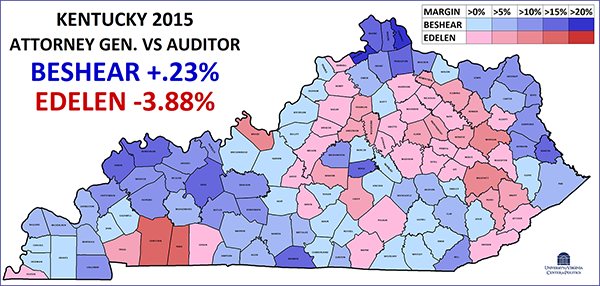

Map 1 compares the margins of Beshear, who was elected state attorney general in 2015 by just two-tenths of a point, to former state Auditor Adam Edelen (D); at the time, Edelen was the incumbent, but was defeated by 3.9%. Beshear ran the furthest ahead of Edelen in Campbell County — he nearly carried it, with 49.5%, compared to Edelen, who lost it by 21%. Between Beshear’s close margin there and its suburban demographics, Campbell would seem to be a “must-win” county for him next week. (Edelen also sought the Democratic gubernatorial nomination this year but lost to Beshear.)

Map 1: Beshear vs. Edelen performance, 2015

At a more general level, Republicans are hoping another historical trend holds next week: Democrats’ penchant for underperforming their polls as election day approaches.

Bevin’s 53%-44% victory in 2015 was considered an upset because he trailed his opponent, then-state Attorney General Jack Conway (D), in most public polls. Conway often polled at 45% or less, and his leads obscured the high volume of undecideds. On Election Day, Conway took roughly 45% while undecideds broke, almost uniformly, Republican.

On one level, this dynamic previewed the 2016 presidential election the next year. Hillary Clinton generally posted small, but consistent, leads in key Rust Belt swing states — namely Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan — but the 50% mark often proved elusive for her. This paved the way for Donald Trump to carry those states with narrow pluralities.

The latest Mason-Dixon poll shows Bevin and Beshear tied at 46%, though both parties claim their internals show their candidate ahead, albeit narrowly. A welcome sign for Bevin in this poll is the uptick in his approval rating; though he’s slightly underwater, at 45/48, it’s a dramatic improvement from his -15% spread from Mason-Dixon’s previous poll.

Bevin will also be aided by a campaign appearance from President Trump on the eve of the election in Lexington, which is in the heart of the state’s 6th Congressional District, another crucial battleground area to watch.

This race is very close to being a Toss-up, and Beshear winning would not be a shock. But because of Kentucky’s Republicanism, we just think Bevin has the clearer path to a plurality.

Mississippi: Election format benefits Republicans

It is inarguable that Democrats got their best-possible candidate for the open Mississippi gubernatorial race this year. Attorney General Jim Hood (D) has won statewide four times, and his cultural conservatism — he is anti-abortion and pro-gun rights — has allowed him to distinguish himself from the national Democratic Party, something Southern Democrats have been trying to accomplish, with decreasing rates of success, for decades.

Meanwhile, it would be unfair to Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves (R) to call him the worst-possible Republican candidate; while he is hardly a beloved figure in state politics, he is a conservative Republican in good standing without major problems.

That said, it is possible that Republicans would be better-positioned in the Magnolia State if their nominee was former state Supreme Court Chief Justice Bill Waller, Jr. The reason is that Waller may have been better able to counter Hood’s appeals to the middle of the electorate by breaking with GOP orthodoxy in key ways. A major fissure between him and Reeves was that Waller backed a gas tax hike to pay for infrastructure improvements as well as a limited expansion of Medicaid, which was made possible by the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare). Reeves, who beat Waller by about eight points in a primary runoff, is a more conservative Republican than Waller. If Hood beats Reeves, his positioning closer to the middle compared to Reeves’ down-the-line conservatism will have helped him.

Fortunately for Reeves, being a conservative Republican is hardly a hindrance in Mississippi, where Republicans almost always come out on top because whites outnumber blacks in the state. To win, Hood likely will need about 25% of the white vote — that does not seem like a big number, but it actually is.

There are a couple of electoral backstops for Reeves, at least one of which is legally solid. Mississippi law requires that a winning gubernatorial candidate win a majority of both the statewide vote and carry a majority of the state’s 122 state House districts. If neither candidate satisfies both of those conditions, the state House will pick the next governor — almost certainly Reeves, given that the GOP has a healthy majority in the chamber.

There are two other candidates, one a Constitution Party candidate and another an independent running on marijuana legalization. One wouldn’t expect either to get many votes, but in a very close race, third-party votes could rob both candidates of a majority. If the House voted to make a candidate a governor as a result of neither winning a majority of the statewide vote, that would be similar to a system used in Vermont, where in both 2010 and 2014, the Democratic-controlled state legislature elected Peter Shumlin (D) governor (Shumlin narrowly won more votes than his opponent but finished short of 50% both times). In other words, this majority-vote requirement is not unique to Mississippi. But the legality of the requirement that the winning gubernatorial candidate win a majority of state House districts is very much an open question, and there is a pending lawsuit challenging the system.

These odd election requirements benefit Reeves, but so does the state’s overall partisanship. Hood is a strong challenger, but we’d rather be Reeves, even though our best intel suggests that the race remains quite close.

That the president remains popular in Mississippi is significant asset for Reeves, and he is deploying the president for a Friday pre-election rally in Tupelo, in the northeastern part of the state. The choice of location is telling.

Hood is from Houston, which is relatively close to Tupelo in the northeast. This area was, at one time, a rich source of Democratic votes: Jimmy Carter carried the entire northeastern corner of the state in both 1976 and 1980. But Democrats generally have struggled mightily in the area recently: Trump carried MS-1, which covers Tupelo, Houston, and northeast Mississippi more generally, by a punishing 65%-32% tally in 2016, up from Mitt Romney’s 62%-37% margin in 2012.

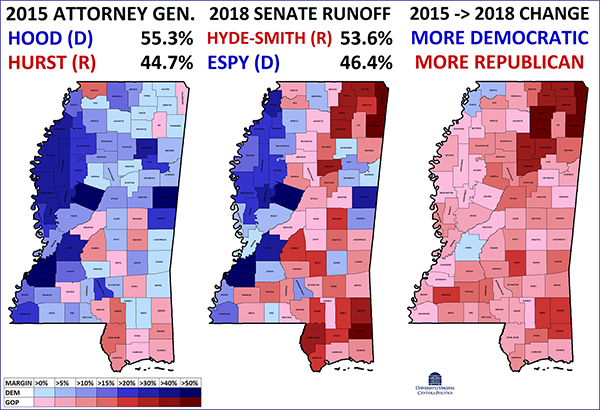

However, when Hood won reelection to a fourth term in 2015, he did well in northeast Mississippi. Map 2 compares his 10-point statewide victory to the 2018 Senate special election runoff, which Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith (R) won over former Rep. Mike Espy (D) by seven points. Note that Hood ran ahead of Espy’s showing almost everywhere, but especially in Hood’s home region. This is a region to watch, as Hood’s home-area appeal is tested by the region’s fondness for Trump.

Map 2: 2015 Mississippi AG race vs. 2018 Senate runoff

Overall, of the three underdogs in Tuesday’s three elections (Republicans in Virginia, Beshear in Kentucky, and Hood in Mississippi), a Hood win would surprise us the most. A lot of that has to do with the inflexibility of the Mississippi electorate in a big statewide race, but one also has to account for the two separate majority requirements that benefit Reeves.

New Jersey: Democrats hope for a darker shade of blue

The following section on New Jersey is written by Ben Kestenbaum of the New Jersey Globe.

Of the four states holding legislative elections in 2019, New Jersey is the only one with a Democratic trifecta. The Garden State was the epicenter of the 2018 blue wave. Democrats flipped four of its congressional districts, leaving Republicans with only one of the state’s 12 seats. Despite low approval ratings and personal scandal, Sen. Bob Menendez (D) was reelected by 11 points. At the legislative level, Democrats are aiming to seize on this momentum by expanding their majority in Trenton.

Members of the state’s lower house, the General Assembly, are up for election next week while the state Senate elections aren’t until 2021. New Jersey is divided into 40 legislative districts, each of which elects one senator and two assembly members. Assembly members are elected concurrently. No district currently sends a split delegation to the General Assembly, which fits in with larger, national partisan trends. Still, there is some crossover between the chambers — in a few districts, one party holds the state Senate seat while the other controls the assembly delegation.

Democrats currently hold a supermajority in the General Assembly, holding 54 of the 80 seats. Going into the 2017 elections, LD-2 and LD-16 sent split delegations to the assembly — Democrats picked up a seat in each, giving them unified control of both. Republicans are aiming to mitigate any further losses.

The Democrats are currently hoping to flip four Republican-held seats: LD-8, LD-21, LD-25, and LD-39. Their most promising pickup opportunity is LD-21, which has voted Democratic in every major statewide race since 2016. Additionally, its incumbent, House Minority Leader Jon Bramnick (R), received some negative press for language on his law firm’s website.

A second strong pickup opportunity for the Democrats is LD-8, located in South Jersey. Though Sen. Menendez lost it in 2018, it supported Hillary Clinton and Gov. Phil Murphy (D) in previous cycles. This was the closest district in 2017, with the Democrats coming within 650 votes of carrying both its seats. A telling omen may be that its senator, Dawn Marie Addiego, recently switched parties, leaving the GOP to become a Democrat.

Two other pickup opportunities for Democrats are LD-25 and LD-39 — both were within three points in 2017. Clinton carried LD-25 by a razor-thin margin, while losing LD-39.

The Republicans are largely on defense, but are still eyeing LD-1, LD-2, LD-11, and LD-16. The GOP’s best target seems to be LD-16. Both its assembly seats have slipped to Democrats in recent cycles, but it still sends a Republican to the Senate.

A special senatorial election in LD-1, based in South Jersey, may offer the GOP an unexpected opening. In 2018, its incumbent, then-Sen. Jeff Van Drew (D), was elected to represent the open NJ-2 in the U.S. House. His successor, appointed Sen. Bob Andrzejczak (D), will run to finish the remainder of Van Drew’s term in this Trump +9 seat.

The other two seats that the Republicans hope to flip are LD-2 and LD-11. In 2017, Democratic assembly candidates held both by 5%.

While an increased Democratic majority likely wouldn’t mean a radical change in state policy, aside from giving Murphy more votes to whip for items such as marijuana legalization, it would provide further evidence that the suburbs are shifting away from the Republicans. Democratic flips in LD-21 and LD-25 would be welcome news for the newer members of the state’s congressional delegation.

Conversely, a strong GOP showing in South Jersey may give Van Drew reason to worry. He said he is unlikely to back a House resolution that formalizes the impeachment inquiry against President Trump, so he is being cautious as he seeks a second term in a district Trump very well could carry again.

2019 Conclusions

We wouldn’t use any of the results from next week as a way of projecting ahead to the 2020 election. That battle is still a year away and the conditions under which it will be contested are as-yet unknown. But what will be interesting to track is whether the nationalization trend holds true. Again, that points toward Republicans in Kentucky and Mississippi and Democrats in Virginia and New Jersey. Reality isn’t always so neat and tidy, though.

P.S. CA-25, PA-17, NC’s districts, and Hagan’s 2008 strength

We had a few other points to make this week, mostly involving the House:

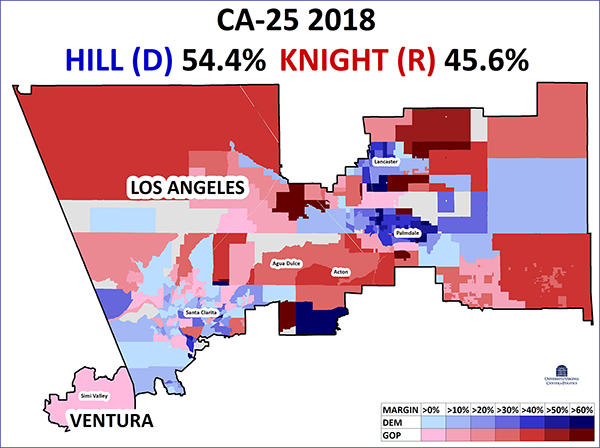

— In California’s 25th District, Rep. Katie Hill (D), announced her resignation on Sunday, in the wake of a bizarre scandal in which she faced allegations of improper relationships with staffers but may arguably also have been the victim of a crime, as intimate photos of her emerged online over the past couple of weeks. Hill, a first-time candidate in 2018, defeated Rep. Steve Knight (R, CA-25) by nearly 9% last year (Map 3) as part of major Democratic gains in California.

Map 3: 2018 election in CA-25

California’s 25th district is based largely in northern Los Angeles County; after narrowly supporting Mitt Romney in 2012, Hillary Clinton carried the district by a more comfortable 7%. Given the terrain and trend of the district, we initially rated it as Likely Democratic for 2020, but given the uncertainty that special elections can bring, Leans Democratic feels more appropriate for now.

This could well be a case where the party in office is, electorally, better off without the incumbent, although that remains to be seen.

In the few days since Hill’s resignation announcement, the candidate field has already started to develop. State Assemblywoman Christy Smith (D), who won a close contest last year in a district that overlaps with CA-25, announced her campaign. On the Republican side, Knight seems ready to launch a comeback, though former Trump campaign adviser George Papadopoulos’ imminent campaign seems to be grabbing more headlines. Papadopoulos pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about his communications with people tied to Russia during the 2016 campaign. There are other GOP contenders as well.

California’s jungle primary will also loom large in this special election, but there is a wrinkle: Typically, there is a general election runoff in California, but in this election, if someone wins a majority in the first round of voting, that person will be elected to the remainder of Hill’s unexpired term without a second round of voting. This will incentivize both sides to rally around a single candidate, but that may not happen.

All things considered, Democrats are favored to hold this blue-trending seat, but Republicans shouldn’t be counted out, and this should be a closely-watched House special election whenever it is ultimately held next year.

— Pittsburgh-area Rep. Conor Lamb (D, PA-17) won two impressive victories during the 2018 calendar year. First, he won a special election in the old PA-18 in March, flipping a district that Donald Trump carried by about 20 points in 2016. In November, none of the 43 Republican-held seats that Democrats flipped voted as strongly for Trump as the old PA-18 did. Then, after the state Supreme Court re-drew the Keystone State’s congressional districts, Lamb ran against another member of the House, Keith Rothfus (R), in a new district that was much less Republican (Trump won it by only about 2.5 points). Lamb beat Rothfus by a dozen points, and PA-17 is the kind of district — suburban and with above-average levels of four-year college attainment — that could flip from Trump 2016 to the Democratic presidential nominee in 2020. Because of Lamb’s electoral track record and the possible trajectory of his district, we consider Lamb to be one of the most secure of the 31 Democrats who hold districts that Trump carried.

We still feel that way, but it appears that Lamb has drawn a potentially viable challenger. After the president recently name-dropped him at a speech, veteran and author Sean Parnell (R) filed to run against Lamb. It remains to be seen whether the first-time candidate can run a successful campaign, but his connection to the president and preexisting media apparatus (he has appeared on Fox News) means he should be able to raise money. He may ultimately be too supportive of the president to win a district that may be lukewarm on Trump, but Parnell at least gives the Republicans the potential to have a strong challenger to Lamb, which they were not guaranteed to have. So we’re moving PA-17 from Safe Democratic to Likely Democratic.

— While we just made two House ratings changes in the Republicans’ favor, we may eventually be making several changes in North Carolina favorable to Democrats. That’s because the state appears likely to feature a new congressional map for next year’s elections.

Earlier this week, a state court blocked the use of the current map, a Republican gerrymander, in 2020. That decision mirrors a similar ruling earlier this year that led to the remap of North Carolina’s state legislative districts, which also were gerrymandered by Republicans. The state’s current U.S. House map has produced a 10-3 Republican edge, a bloated GOP advantage that doesn’t really reflect the state, which is Republican-leaning but also very competitive.

It’s hard to say precisely what will happen going forward, but a new map should allow the Democrats to make gains in the state. Even gaining a seat or two would help provide a buffer for Democrats if they lose seats elsewhere, and Republicans will need to net about 20 seats overall to win a majority next year.

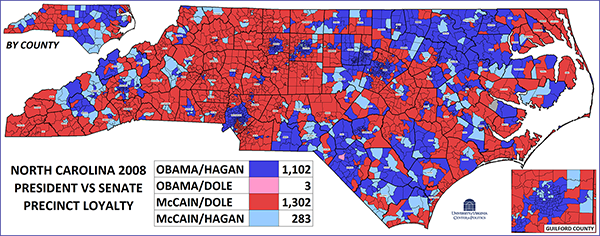

— Speaking of North Carolina, if you’ve enjoyed the maps that have been featured in recent editions of the Crystal Ball, it may be partially due to the late Sen. Kay Hagan (D-NC). Hagan was an early supporter of Associate Editor J. Miles Coleman’s political cartography. After battling encephalitis for nearly three years, Hagan died on Monday. As we send out best wishes to the late senator’s family, we wanted to take a brief look back at her 2008 election.

As the 2008 campaign season got underway, Democrats were excited about their prospects of winning the Tar Heel State’s 15 electoral votes and were optimistic that they’d hold the governorship. A lingering frustration, though, was that several of their bigger names had passed on the Senate race that year.

Initially, then-Sen. Elizabeth Dole (R-NC) seemed to have an aura of invincibility. Despite her somewhat tenuous connections to the state — she was originally from the Piedmont town of Salisbury but spent most of her (distinguished) career in Washington, D.C. — she was recruited by national Republicans in 2002. Called the GOP’s “dream candidate,” she was, at a time, rated one of Gallup’s “most admired women in the world.” Sure enough, Dole won her first election by 9%, holding the open seat of long-serving Sen. Jesse Helms (R-NC), a conservative icon who retired in 2002 and died in 2008.

After the May 2008 primaries, Democrats began to coalesce behind their nominee, an obscure state senator from Greensboro, Kay Hagan. Hagan steadily gained in the polls, eventually pulling about even with, or slightly ahead of, the incumbent. In the closing weeks of the campaign, Hagan was helped by one of Dole’s ads that backfired spectacularly. Hagan’s response is considered one of the great counterpunches in recent American campaign history and cemented her lead.

Ultimately, in a culmination of Dole’s missteps, the blue environment of the year, and her own strengths, Hagan flipped the seat by 8.5%. Hagan became the first woman in Senate history to win her seat by defeating an incumbent woman. She found crossover votes in all corners of the state, carrying 283 precincts that didn’t support President Obama (Map 4), who only narrowly carried the state himself.

Map 4: Kay Hagan’s overperformance over Obama, 2008

Six years later, Hagan lost a close reelection bid to now-Sen. Thom Tillis (R), who himself faces a challenging reelection contest next year.

During each Senate cycle, partisans on both sides will inevitably complain about recruitment in one race or another. One of the larger lessons of the 2008 North Carolina Senate race is that strong candidates can, seemingly, come out of nowhere.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.