Rating the New Missouri House Map

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Over the weekend, Gov. Mike Kehoe (R-MO) signed off on a mid-decade gerrymander designed to give Republicans all but one of the 8 House seats in his state.

— Aside from turning a blue district in the Kansas City area red, the map fortified the St. Louis-area MO-2, the most marginal GOP-held seat on the map.

— Though we are assuming the new map will be operative, there are some efforts to stop, or delay, the map’s implementation, including court challenges and a potential ballot measure.

— In Arizona, Rep. David Schweikert (R, AZ-1) got into his state’s gubernatorial race, which leaves open a competitive seat in the Phoenix area.

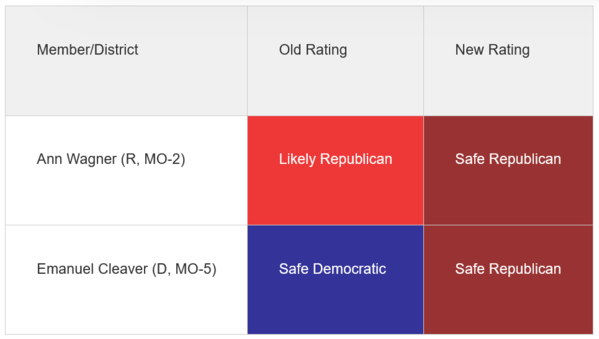

Table 1: Crystal Ball House rating changes

Missouri passes 7-1 map

On Sunday, Gov. Mike Kehoe (R-MO) signed off on a mid-decade redistricting map—his signature came just under a month after he called his legislature into a special session to pass a map that he, and President Donald Trump, favored. With that, Missouri became the third state this year where a mid-decade redistricting map made its way through the legislative process.

While the new Missouri map, unlike its counterparts in California (which has to be approved by voters) and Texas, will not result in a windfall of seats for either party, it did make some significant, and pro-Republican, changes to the map it replaced.

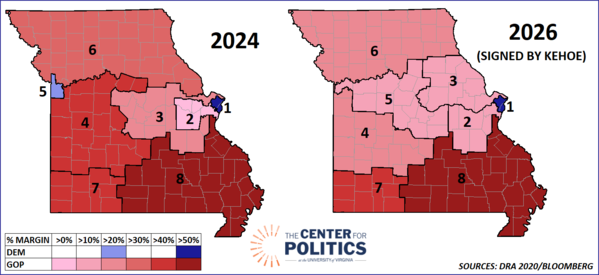

Map 1 compares the outgoing map, which was in place for the 2022 and 2024 elections, to the one that Republicans recently passed. The images in Map 1 are colored based on their 2024 presidential vote. We will get more into the details below.

Map 1: 2024 vs 2026 Missouri congressional maps

In the postwar era, Jackson County, which includes most of Kansas City, has always sent at least one Democrat to the House. Republicans’ primary goal with this new map was ending that nearly 80-year Democratic streak by targeting Rep. Emanuel Cleaver (D, MO-5). In the St. Louis area, Rep. Wesley Bell, the only other Democrat in the state’s federal delegation, represents the plurality-Black 1st District—it gave Kamala Harris almost 80% last year, so the district is too blue for Republicans to cleanly crack, and doing so would be legally dubious. But Cleaver’s 5th District stood out as a much more obvious GOP redistricting target. It is majority white, and while it gave Harris just over 60%, it is bordered by two districts, MO-4 and MO-6, that gave Trump about 70% apiece. During the regular, post-2020 redistricting session, state Republicans considered cracking MO-5 but ultimately decided not to—a few years later, pressure from the White House clearly made the difference.

As Cleaver’s district reached east to include more than a dozen (mostly very red) counties, Kansas City was chopped up as mappers aimed to dilute its Democratic strength. On the version that was used in the 2022 and 2024 elections, more than 80% of Kansas City proper was located within the 5th District. The balance, which included the parts of the city that are located in Clay and Platte counties, was in MO-6, a red seat held by Rep. Sam Graves, the dean of the Missouri delegation. Under the proposal that the legislature passed, Kansas City is much more fractured: while MO-5 retains a 40% plurality of the city, MO-6 now takes close to 35% of the city, and MO-4, a red district to the south, takes 25%. On the new 5th’s eastern edge, GOP mappers apparently did not feel as much need to split up Columbia, home to the University of Missouri. While MO-5 takes in part of Columbia’s Boone County, the city itself is now entirely within the 3rd District; on the old map, Columbia itself was split about evenly between Districts 3 and 4.

In terms of partisanship, the 5th District moves from a solidly blue seat to one that is very representative of the state overall: the new MO-5 would have given Trump a 58%-40% margin last year, which was identical to his statewide showing. Cleaver himself has suggested he’d still run for a 12th term, and the redrawn district has not voted exclusively Republican in some recent statewide elections: It backed Democratic nominees for governor and Senate in 2016, and former state Auditor Nicole Galloway, the last Democrat to win a statewide election there, carried it by double-digits as part of her 50%-45% win in 2018. But each of those cases involved especially strong Democrats—or, especially weak Republicans—and, perhaps more importantly, there are no House Democrats that currently hold double-digit Trump-won seats. So, assuming the map stands (more on that below), we are moving our rating for MO-5 all the way from Safe Democratic to Safe Republican. While both MO-4 and MO-6 become several points less red, neither are realistic Democratic targets.

In the St. Louis area, Republicans took the opportunity, as they did in their last remap, to make Rep. Ann Wagner’s (R, MO-2) district redder. In 2020, Wagner had the most closely-divided district in the nation: calculations from Daily Kos Elections, which is now The Downballot, showed Trump winning the seat by only 115 votes out of the 450,000 it cast. For 2022, though it remained a seat basically centered on St. Louis’s closer-in suburbs, Republicans made its character more rural—the addition of two red counties bumped Trump’s 2020 margin up to 53%-45%. Despite Trump’s improvement, both nationally and in Missouri, he held MO-2 by the exact same 8-point margin in 2024. In part because of that static trend, we rated MO-2 as Likely Republican for 2026.

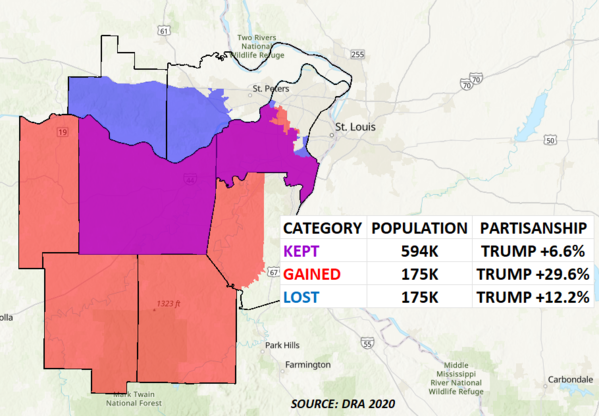

Under this mid-decade remap, MO-2 moves out of suburban St. Charles County and reaches south to take in all, or parts, of four even redder counties that were previously in MO-3. Map 2 shows the changes.

Map 2: MO-2 geographic and partisan changes

With those changes, Trump would have carried the new MO-2 by just over 11 points in 2024. For our purposes, that shift justifies moving MO-2 off the board—we are changing our rating there to Safe Republican.

Because the map was passed by the state legislature and signed by the governor, we are assuming it will be operative for the 2026 elections. However, the map faces some obstacles—and we will adjust accordingly if it is struck down, or if its implementation is delayed until after the midterms.

The special session has prompted a flurry of legal and organizational action, and developments have moved rapidly. To start, the map has prompted several individual lawsuits. One such challenge alleges that voters in one precinct were placed in multiple districts. The ACLU is arguing that one voting tabulation district was assigned to both Districts 4 and 5. Republicans dispute this (see the linked Missouri Independent article for more on the case). If the challengers are correct, aside from making the map unconstitutional, it would hint at some sloppy map-drawing—while the Kansas City area does have some small precincts that can be hard to catch, there is open source redistricting software that can check for such errors. Another lawsuit focuses more on process, arguing that the state constitution bars mid-decade redistricting.

Aside from the court challenges, the group People Not Politicians is also leading a petition effort to put the map up to a statewide vote. After it was rebuffed last week by the Missouri secretary of state, People Not Politicians appears to have successfully initiated a petition to put the map up to a statewide vote. People Not Politicians will have until December to gather more than 100,000 signatures—if they can, the new map would not become operative until there is an up-or-down statewide vote on it. Voters could still approve the map—Missouri is a red state, after all, and the national nature of the potential referendum could help their side. Although, as St. Louis Public Radio notes in the article linked to above, if the vote is scheduled for November 2026, the map, even if passed, obviously wouldn’t be able to take effect until 2028.

On a related note, another piece of legislation that passed in last month’s special session had to do with the ballot initiative process itself. In what will be known as Amendment 4, a GOP-backed initiative will appear on the 2026 statewide ballot that would significantly raise the threshold for future ballot measures. If passed, Amendment 4 would require that citizen-initiated ballot measures pass in all eight of the state’s congressional districts. Amendment 4 will be one of the key races, aside from the usual partisan contests, that we’ll be following next year. In 2023, Ohio Republicans backed a similar measure aimed at raising the standard for ballot measures in advance of a statewide vote on abortion rights. Clearly, Ohio voters didn’t want to give themselves less say in government, as they defeated the measure by 14 points.

In other Republican-led states, the Trump administration is continuing to pressure leaders to redistrict—such is the case in Indiana and Nebraska. Another is New Hampshire, which is the only Harris-won state that currently has a GOP state governing trifecta. Gov. Kelly Ayotte (R-NH), though has insisted mid-decade redistricting is off the table. The White House is reportedly threatening Ayotte with a primary challenge—nominating a Trumpier Republican in a state that the president himself lost three times does not strike us as a politically adept move, though. In fact, her independence on redistricting could be part of why Ayotte’s approval has gone up over the last couple of months, according to tracking polls by the University of New Hampshire.

P.S. Schweikert launches gubernatorial run

Earlier this week, Rep. David Schweikert (R, AZ-1), who had been rumored to be kicking the tires on a potential gubernatorial run for the last month or so, went ahead and entered the contest. Despite some ethics woes, Schweikert has continually held on in a marginal seat over the last several cycles. The GOP primary for governor, though, had already begun to take shape, as former state Board of Regents member and 2022 candidate Karrin Taylor Robson was running again, and Rep. Andy Biggs (R, AZ-5), a favorite of the more conservative wing of his party, got into the race earlier this year. Temperamentally, Schweikert has not been as high-profile as Biggs, but he might not be viewed by grassroots conservatives with the same suspicion that Taylor Robson is.

Typically, Trump-endorsed candidates win GOP primaries, but in a bit of an unusual case, the president has endorsed both Taylor Robson and Biggs—perhaps that ambiguity could render those endorsements less meaningful, which may give Schweikert an opening. Either way, we are expecting a competitive Republican primary. Gov. Katie Hobbs (D) has gotten some minor opposition but remains overwhelmingly favored for renomination. Our Toss-up rating for the race stands.

Speaking of Toss-ups, that was also the rating that we had in place for Schweikert’s AZ-1, which is now open. Scottsdale is the anchor of this eastern Maricopa County district. In 2020, Joe Biden carried AZ-1 by a point and a half but Trump then carried it by 3 points last year. However, that 4.5-point swing to Trump in AZ-1 was less than the nearly 6-point shift that Arizona saw overall. Part of that probably had to do with demographics: According to Redistricter, AZ-1 is both the whitest district in the state and has the highest college attainment rate, with about 50% of residents over 25 holding a bachelor’s degree. In other words, it is probably a seat that would be part of the next Democratic House majority—especially in light of the redistricting wars. For now, though, we are holding our Toss-up rating there as we see how the primary fields evolve.

One added wrinkle here is that Arizona holds its primary somewhat late in the calendar—early August—and sometimes those who face competitive primaries are perceived to have trouble pivoting to the fast-approaching November general election. Democrats had a competitive primary last cycle and appear to be headed toward one this time; meanwhile, Republicans may now have one of their own if a number of Republicans jump into this primary. That alone could make the seat a little more difficult for Republicans to defend.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.