Notes on the State of Politics: Iowa Special Elections, Utah Redistricting

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— In Iowa, Democrats continued to rack up special election overperformances by flipping a Trump-won state Senate seat that is based in Sioux City.

— Democrats have broken the GOP’s supermajority in the state Senate, although Republicans still hold comfortable majorities in both chambers of the legislature.

— A judge threw out Utah’s current House map, a GOP gerrymander, ruling that it does not fit with the guidelines set by a 2018 voter-approved state ballot issue.

— A fairer map of Utah would probably have one blue seat and three red ones, instead of four red ones, though Utah Republicans may try to delay a new map’s implementation.

Sioux City breaks Iowa GOP’s supermajority

Tuesday night, Democrats extended their long-running streak of solid special election showings in Iowa. In a race that saw involvement from the national party, state Sen.-elect Catelin Drey (D) defeated Republican Christopher Prosch (R) by a roughly 55%-45% margin in state Senate District 1. Drey’s victory represents the fourth instance where Democrats have significantly overperformed Kamala Harris’s 2024 showing in the state.

In January, Democrats flipped a state Senate district in the eastern part of the state that was held by now-Lt. Gov. Chris Cournoyer (R) before she assumed her current job. In the spring, the line of Democratic overperformances continued with a pair of state House special elections, though neither instance resulted in a flip. Republicans held onto HD-100, another eastern seat that hugs the Mississippi River, by about 3 points after it backed Donald Trump by nearly 30% in 2024. Then in April, Democrats retained HD-78, a seat that backed Harris by a two-to-one margin, by a nearly 80%-20% vote.

Iowa’s 1st state Senate District, the scene of this week’s election, is in the northwestern part of the state and centers on Sioux City. One of the chamber’s few relatively marginal districts west of the Des Moines metro area, SD-1 has not deviated much from Iowa’s overall picture in recent statewide elections. After giving Barack Obama comfortable margins, it now has a mild GOP lean and backed Trump three times.

In June, first-term GOP state Sen. Rocky De Witt passed away, triggering a special election in SD-1. Bleeding Heartland’s Laura Belin, a liberal commentator, has a nice explainer of the contours of the race that ensued. Aside from Democrats’ seemingly built-in special election advantage, two factors that seemed to shape the outcome were Drey’s financial advantage and Republicans selecting a riskier than necessary nominee.

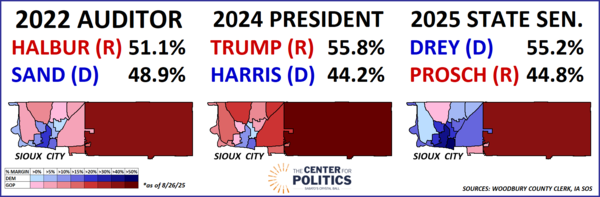

Map 1 compares Tuesday’s special election to some other key statewide results in the district. As mentioned earlier, while the district is now red at the presidential level, even state Auditor Rob Sand, who was the only winning statewide Democrat in 2022 and is now the leading candidate for his party’s gubernatorial nod, narrowly missed carrying it.

Map 1: Recent elections in Iowa state Senate District 1

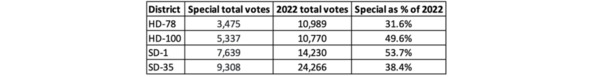

Of course, as is usually the case in special elections, turnout was not at midterm or presidential levels. Drey and Prosch combined for about 7,600 votes—the major party presidential candidates got over 21,000 votes in the district last year, and the auditor’s race saw about 14,000 votes cast. Compared to recent special elections, though, turnout this week was relatively strong. Table 1 looks at turnout in the 4 Iowa special elections that have taken place so far this year. The SD-1 race was the only instance where turnout exceeded 50% of what the 2022 general election saw. Still, we should expect turnout to be markedly higher in the 2026 midterm (all of these seats that had special elections this year will be back on the ballot next year).

Table 1: Turnout in 2025 Iowa special elections

Something that may have been driving that was the stakes: with this flip, Democrats have broken the Republicans’ supermajority in the chamber. Democrats will have to defend the seat in next year’s regular election, but for practical purposes, they now have some increased clout in the legislature: Gov. Kim Reynolds (R), who is not seeking reelection next year, will now need at least some Democratic support for her appointments.

The turnout edge that Iowa Democrats likely enjoyed in these special elections probably won’t be as pronounced in the 2026 general election, which will feature a larger electorate. However, the Democratic overperformances may be directionally suggestive as an indicator of the broader political environment in Iowa and elsewhere—Democrats have generally been doing well in special elections relative to the 2024 presidential results.

Utah joins the (bee)hive of redistricting activity

Most of the redistricting back-and-forth that has flared up in recent months can be directly attributed to President Donald Trump’s involvement in what is typically a once-in-a-decade process. However, even before the Trump White House began imploring red states to redraw their lines, Utah was seen as a realistic prospect for mid-decade redistricting. On Monday, the Beehive State took a solid step towards implementing a new map, and any changes there seem more likely to benefit Democrats.

In 2018, Utah voters narrowly passed Proposition 4, a measure that created an independent redistricting commission with the power to recommend maps to the GOP-dominated state legislature. But two years later, legislative Republicans passed SB200, legislation that had the effect of watering down Proposition 4. Though the commission could still suggest maps, the legislature, which retained its own redistricting committee, was not obligated to accept its products.

Sure enough, though the commission created several maps, legislative Republicans passed their own gerrymander that was meant to protect their 4-0 advantage in the state’s delegation. As a result, a coalition led by the League of Women Voters and Mormon Women for Ethical Government sued the legislature, arguing that SB200 unconstitutionally overrode a voter-approved measure.

A little over a year ago, the Utah Supreme Court effectively sided against the legislature, ruling that Proposition 4’s reforms were constitutionally protected. The case was then sent back to a lower court. On Monday, Judge Dianna Gibson ruled the legislatively drawn maps were created in an unconstitutional manner, and thus couldn’t be used.

Before Republicans passed their own gerrymander in advance of the 2022 midterms, the commission established by Proposition 4 produced three proposals for the legislature. Each of those three maps would have created a Safe Democratic seat that includes Salt Lake City along with three other Safe Republican districts. While the SH2 proposal creates the most marginal such district, the Salt Lake City district would have still backed Kamala Harris by 18 points last year—so, under those lines, Republicans couldn’t realistically hope to hold all 4 of their current seats. As an aside, the SH2 proposal was created by Stuart Hepworth, who usually has some insightful takes on the state and did a lengthy thread explaining the map’s details.

With the ball now back in the legislature’s court, there seems to be some uncertainty over next steps. Not surprisingly, the president is not happy about the ruling. While it’s possible—if not likely—that Republicans will appeal Gibson’s decision, the state Supreme Court has already ruled against them on this matter. The U.S. Supreme Court does not seem likely to intervene in favor of Utah Republicans either, as it has allowed state courts to make their own determinations on redistricting based on state law (even as the federal high court has declined to intervene against partisan gerrymandering at the federal level). With that, Republicans’ best strategy might just be to try to delay the implementation of new maps until after the 2026 midterms.

But what if the legislature actually tried to produce a map? Legislators may defer back to the commissions’ three maps, but they could possibly also attempt to draw their own map and defend it, although Gibson gave them less than a month to submit a new plan. Though Republicans’ path of least resistance in this scenario—a path the Trump White House would probably not like—likely involves conceding a deep blue Salt Lake City district, there are other ways the state could be drawn.

Utah was one of the states that we evaluated a few weeks ago as we looked at states that currently have one-party delegations in the House. For that article, we created a sample plan that included two very close Harris-won seats that took in parts of the Wasatch Front. By a similar token, it is also easy to create two marginal Trump-won seats in that area—although with what could be a Democratic-leaning midterm coming up, single-digit Trump seats would not be guaranteed GOP holds. If Utah Republicans follow the lead of their Alabama counterparts—during a court-ordered round of redistricting in 2023, they submitted maps that were cleaner than the existing plan but still preserved their partisan advantage—they could try for a map like this. Essentially, while it keeps two deep red seats, Salt Lake City is placed in a geographically vast Trump +12 district that includes St. George, and a final Salt Lake County-only district could still be Trump +7. A plan like that would only split Salt Lake County two ways (which would be necessary on any map, as it is more populous than the ideal for a congressional district) although it may not hold up under judicial scrutiny.

Anyway, Utah has now joined the growing list of states that may have a new congressional map this year, albeit because of judicial intervention as opposed to the preferences of the state’s majority party.

The big picture in redistricting

In Texas, the Republican legislature passed its new Trump-sanctioned gerrymander over the weekend. Though the map that ultimately made it through both chambers of the legislature included some small changes from the original plan that we outlined in late July, for the purposes of our ratings, we would move 4 seats into the GOP’s column. However, Gov. Greg Abbott (R-TX) has not signed off on the new plan yet—when applicable, it is our custom to wait for gubernatorial approval before assuming that new maps are operative—so we are holding off on formalizing new ratings.

Still, we can provide a sense as to how the Texas remap—and subsequent remaps—might change the big picture in the House.

Right now, our Crystal Ball ratings show 209 seats as Safe/Likely/Leans Democratic, 207 Safe/Likely/Leans Republican, and 19 Toss-ups. When Abbott signs this map, that will change to 211 at least Leans R, 206 at least Leans D, and 18 Toss-ups.

However, if Democrats’ proposed California map is implemented, that would then flip to 211 at least Leans D, 206 at least Leans R, and 18 Toss-ups, even taking Texas into account.

So, if re-redistricting were limited to just Texas and California, Democrats would probably come out ahead, although other red states like Indiana, Missouri, Ohio, and Florida could produce new Republican seats, giving the GOP an overall edge from redistricting even taking California into account. Of course, if the California redistricting ballot measure fails, Republicans could pick up the better part of a dozen seats.

Over the weekend, Gov. Wes Moore (D-MD) opened the door to redrawing his state’s lines, although Democrats, who hold 7 of Maryland’s 8 seats, could only gain one additional seat there. A Democratic 8-0 map of Maryland could also run into some legal problems (court intervention submarined such a plan in advance of the 2022 elections), There’s also Utah, discussed above, which could help Democrats, and potentially other states too.

If the environment is blue enough next year, Democrats could still overcome the net loss from redistricting (even if California fails to redraw), but if 2028 is more of a neutral year, Republicans could have an easier time regaining the chamber.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.