The Governors, Part Two: Familiar Battlegrounds Dot 2026 Map, but Watch for Upsets in Open Seats

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Many of 2024’s top presidential battlegrounds will feature high-profile gubernatorial elections in 2026.

— Arizona and Michigan start as the only two Toss-ups in our initial ratings.

— Be on the lookout for upsets thanks to the high number of open seats, perhaps coming from the long list of races that start rated as Likely for one side or the other.

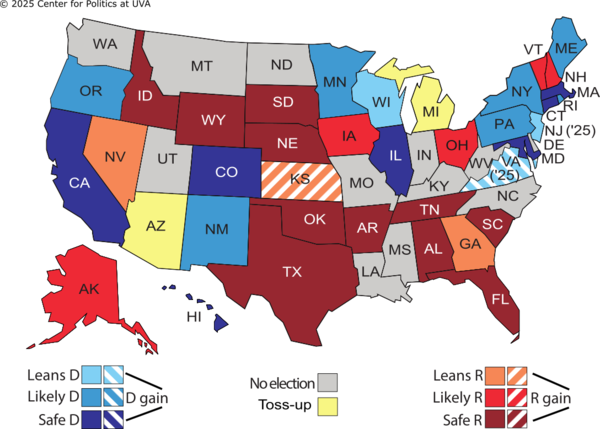

Map 1: 2025/2026 Crystal Ball gubernatorial ratings

Our first gubernatorial ratings

We often note the tendency for the president’s party to lose ground in the House and the Senate in midterms: The president’s party has lost House seats in 18 of the last 20 midterms (covering the post-World War II era), while the president’s party has lost Senate seats in a more modest 13 of the last 20.

This tendency toward presidential-party seat loss also extends to governorships, with the president’s party losing governorships in 16 of the 20 midterms in that timeframe.

In wave years, the president’s party predictably takes a beating in gubernatorial races. The four midterms between 2006-2018 all saw the president’s party lose at least three net governorships, while years that were more mixed saw smaller levels of change—for instance, Democrats actually netted two governorships in 2022. But part of the reason for the differences between cycles is whether many incumbents are running or not; 2022 was also an incumbent-heavy year that included Democrats flipping deep-blue open seats Maryland and Massachusetts as popular GOP incumbents in both states left office. While incumbency seems to generally be declining in value in federal races, it may still be a bit more important in gubernatorial races, which don’t seem to be quite as tied to nationalized political trends. In fact, the Center on the American Governor at Rutgers University’s Eagleton Institute of Politics has found that the reelection rate for incumbent governors has actually been higher in recent years than it’s been in the overall postwar era.

An average of a little under 23 governors have sought reelection in midterm election years since 1950, again according to the Rutgers data. In 2026, 20 of the 36 races next year, at most, will feature an incumbent running for reelection, so this will be a higher-than-average year for open seats.

The high number of open seats makes us think that we could see an upset or two in a state we might not expect. Republicans, for instance, flipped the aforementioned blue states Maryland and Massachusetts as open seats in the good Republican environment of 2014. In 2018, Democrats won what became an open governorship in red state Kansas amidst their wave.

The number of open seats could grow, too. Several incumbents who will have served at least 8 years in office at the end of their current terms but are eligible to run for reelection have not yet made formal announcements about their future, such as Govs. JB Pritzker (D-IL) and Tim Walz (D-MN). Additionally, now-Gov. Larry Rhoden (R-SD) ascended to his state’s governorship after term-limited Gov. Kristi Noem (R) left office to become Secretary of Homeland Security; while Rhoden is an unelected incumbent, he would technically be an incumbent seeking reelection if he seeks a full term in office in his own right.

We are focused on incumbency because changes in party control of state governorships have much more often come in open seats in recent years. Let’s go through some of the recent history:

2022: Of four party changes, only one came through a defeated incumbent. Now-Gov. Joe Lombardo (R) unseated Gov. Steve Sisolak (D) in Nevada. Meanwhile, Democrats flipped open seats in Arizona, Massachusetts, and Maryland.

2018: Democrats flipped seven governorships, but only two of them came from defeating Republican incumbents in the general election: Bruce Rauner in Illinois and Scott Walker in Wisconsin. Meanwhile, Republicans flipped Alaska as independent incumbent Gov. Bill Walker dropped out shortly before the election.

2014: Republicans flipped four Democratic-held governorships, but they defeated only one incumbent (Pat Quinn in Illinois) while doing so. Meanwhile, Democrats defeated the very unpopular Tom Corbett (R) in Pennsylvania, and the aforementioned Walker defeated Gov. Sean Parnell (R) in Alaska.

2010: Of 17 total seats that changed partisan hands—resulting in Republicans netting six governorships—only two involved incumbents losing in the general election: Govs. Chet Culver (D-IA) and Ted Strickland (D-OH).

2006: Democrats netted six governorships, but they only unseated one incumbent: Gov. Bob Ehrlich (R-MD)

2002: In a year with a tremendous amount of turnover—a majority of the governorships (20 of 36) changed partisan hands, including a couple of independent-held governorships reverting to major-party control—only four incumbents lost in the general election. Republicans unseated first-term Democratic incumbents in realigning Southern states that have not elected Democratic governors since—Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina—while Democrats beat an unelected Republican incumbent in Wisconsin: Scott McCallum had taken over for Tommy Thompson after the latter became George W. Bush’s first Secretary of Health and Human Services. Despite all of the turnover, Republicans only lost one net governorship, part of their overall impressive performance in George W. Bush’s first midterm.

So recent history suggests that we are likelier to see party changes in open seats than in states defended by incumbents, although it would also be way too simplistic to just automatically assume that every incumbent will win.

The states that got the most attention in the presidential race last year feature prominently in this year’s most competitive gubernatorial races. Of those seven states—Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—all but North Carolina have gubernatorial elections in 2026, and five of the seven are rated in the competitive Toss-up or Leans categories to begin the cycle. But there are a number of other competitive or potentially competitive other races next year in states outside of last year’s core presidential battleground.

Let’s go through some of the highlights of the ratings:

— In our initial 2025-2026 ratings, there are only two states where the current incumbent party is an underdog in our ratings: the 2025 race in Virginia, which we discussed yesterday, and the 2026 race in Kansas, an open seat where a term limit prevents Gov. Laura Kelly (D) from running for reelection. One would expect Kansas to revert to Republican control even though the state is perhaps not quite as red as it used to be (but Donald Trump still won the state by 15-20 points in all three of his elections). The candidate fields are uncertain on both sides, with Secretary of State Scott Schwab (R) the most significant announced candidate so far. It does seem reasonable to expect that the GOP will have a stronger candidate than current state Attorney General Kris Kobach (R), who rebounded to win his current job in 2022 but was a fairly weak opponent for Kelly in 2018 (Kelly also benefited from the unpopularity of Sam Brownback, the GOP governor elected in 2010 and 2014—Brownback left for an ambassadorship in early 2018 and was replaced by Jeff Colyer, who then narrowly lost the GOP primary to Kobach).

— The only incumbent starting in the Toss-up category is Gov. Katie Hobbs (D-AZ). Hobbs also benefited from a weak opponent in 2022—Republican Kari Lake (who went on to lose a Senate race in 2024)—and may face a stronger challenger in 2026, although she is not guaranteed to. Donald Trump has endorsed both wealthy businesswoman Karrin Taylor Robson—who quite possibly would have beaten Hobbs had she not lost the 2022 primary to Lake—as well as right-wing Rep. Andy Biggs (R, AZ-5), a more recent entrant who would be the more enticing opponent for Hobbs. Arizona lurched back to the right in 2024 after drifting toward Democrats in 2020—it was Trump’s best state among the seven key states last year—and while Hobbs has an OK approval rating, we think she could be in for a difficult reelection. Hobbs did avoid a primary of her own when Secretary of State Adrian Fontes (D) elected to run for reelection, but there nonetheless is some tension in the state Democratic Party in a state where internal Republican upheaval has been more common (the state’s Democratic Party chairman is currently feuding with the state’s two Democratic senators).

— Michigan, another place where Democrats are playing defense, also starts in Toss-up. Outgoing Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, elected to his current job as a Democrat, is currently running for governor as an independent, which complicates the overall picture as term-limited Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D) attempts to hand off the governorship to another Democrat. A Democrat has not succeeded another Democrat as Michigan governor since 1960, although these sorts of historical streaks are made to be broken—we once noted how Pennsylvania had a longstanding trend of alternating between eight years of one party followed by eight years of another. That was true until it wasn’t: Democrats have now won three straight elections there and Gov. Josh Shapiro (D) is favored to win a fourth. The major parties seem likelier than not to have credentialed candidates in this race: for Democrats, Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson and Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist are in the field, while Rep. John James (R, MI-10), who ran respectable races for Senate in 2018 and 2020, is the early frontrunner among Republicans.

— Another open seat in a battleground state, Georgia, could also conceivably be a Toss-up, but we’re giving Republicans the benefit of the doubt there to start. Popular term-limited Gov. Brian Kemp (R) could be replaced as the GOP standard-bearer by another statewide elected official, maybe Attorney General Chris Carr (who is already running) or perhaps someone else. Meanwhile, the Democrats’ most obvious candidate, Rep. Lucy McBath (D, GA-6), was set to run but recently suspended her campaign, citing her husband’s health. The Democrats’ 2014 nominee, former state Sen. Jason Carter (whose grandfather is the late Jimmy Carter), also said he would not run, citing his wife’s health. Democrats may yet produce a strong nominee, but the current contenders are less proven: state Sen. Jason Esteves (D) just announced, and former Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms (D) appears headed toward a run. Stacey Abrams, the 2018 and 2022 nominee, also apparently has not ruled out running, but after her statewide losses, Republicans certainly do not fear her. Democrats have broken through at the federal level in Georgia, but they have yet to do so at the state level. Next year might be the year, but we want to see how the race develops before calling it a true Toss-up.

— A nod to incumbency mainly explains why we rate Govs. Joe Lombardo (R-NV) and Tony Evers (D-WI) in the Leans column as opposed to Toss-up in their respective battleground states. Lombardo is seeking a second term while Evers has not yet announced whether he will seek a third; recent nonpartisan polling has shown each around 50% approval. Lombardo has already drawn a credible challenger, state Attorney General Aaron Ford (D), and former Gov. Steve Sisolak (D) is apparently considering a rematch with Lombardo. The GOP field in Wisconsin is still forming.

— If Democrats want to expand the map beyond the targets we’ve already discussed, there are at least five states rated as Likely Republican that they will monitor. If popular Gov. Phil Scott (R-VT) does not seek reelection to a sixth, two-year term, Democrats would immediately become big favorites to flip the governorship of what is one of the bluest states at the federal level. That said, Scott did help his new, separately-elected lieutenant governor, Democrat-turned-Republican John Rodgers, win an upset in 2024, and Rodgers would at least give Republicans a credible candidate to succeed Scott in a state that, like others in New England, is receptive to moderate GOP governors. Next door in New Hampshire, new Gov. Kelly Ayotte (R) will presumably be running for a second, two-year term; one wouldn’t expect her to lose so shortly after entering office, but New Hampshire is a competitive state and Democrats could compete there under the right circumstances. Alaska, Iowa, and Ohio are all open seats where Republicans are playing defense. Democrats do have promising potential candidates in all three: former Rep. Mary Peltola, state Auditor Rob Sand, and former Sen. Sherrod Brown are all apparently considering running in Alaska, Iowa, and Ohio, respectively. The GOP fields in Alaska and Iowa—where Gov. Kim Reynolds (R) only recently announced that she would not seek a third, full term in office—are still forming, while 2024 Republican presidential gadfly Vivek Ramaswamy has established himself with Trump’s endorsement as the nomination favorite in Ohio. Amy Acton (D), who built something of a name for herself as the Ohio Department of Health director during the early days of the pandemic in 2020, is also running there. If Peltola runs, Alaska could go to Toss-up; we’re less sure about how we’d handle Iowa and Ohio. Perhaps Democrats could compete for the open seat in Florida or against Gov. Greg Abbott (R-TX) as he seeks a fourth term, but discouraging recent results for Democrats in both states and other factors prompt us to start both as Safe Republican as opposed to Likely.

— Of the several states rated Likely Democratic, the one that is going to get the most attention, at least initially, is New York. Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) has been consistently unpopular and could face a real primary, and Republicans did run a competitive race against her in 2022. Donald Trump also made great strides in the state in 2024, although he still lost it by double digits. Republicans may have a prominent candidate. Rep. Mike Lawler (R, NY-17), one of just three Republicans nationwide who holds a district that Kamala Harris carried for president, would probably be the strongest possibility. Rep. Elise Stefanik (R, NY-21), who may be casting about for something else to do after she was denied an appointment to become ambassador to the United Nations on account of the GOP’s thin House majority, has also been mentioned recently. A recent poll showed Stefanik dominating Lawler and another possible candidate, Nassau County Executive Bruce Blakeman, in a hypothetical primary. That actually seems plausible to us, given that Stefanik likely has good name ID as a prominent House member for several cycles, and she is also close to Trump, an asset in a GOP primary. But that closeness to Trump likely would not be an asset in a general election in a still-blue state in 2026. New York merits watching, but a lot of things would need to go right for Republicans to really compete in this race, despite Hochul’s troubles. Neighboring Pennsylvania, where the aforementioned Shapiro could use a solid reelection as a springboard to a 2028 presidential bid, is also a possible Republican target given the party’s growth there. But Shapiro remains popular and formidable; we’ll have to see how strong the GOP nominee is. Of the other Likely Democratic states, Maine could come online as an open seat for Republicans, particularly if an independent emerges that splits the vote in an advantageous way for the GOP—that helped former Gov. Paul LePage (R-ME) win victories in 2010 and 2014 without winning a majority of the vote (although he came close in the latter contest). But Democrats seem clearly favored to start. Also in New England, Gov. Dan McKee (D-RI) seems likely to face a primary after narrowly winning nomination as an unelected incumbent in 2022; whether a competitive primary would open any doors for Republicans in a general election is unclear. Oregon, where Gov. Tina Kotek (D) will likely be seeking a second term, was a major GOP target in 2022, but we doubt it’s as attractive of a target this time even as Kotek’s numbers are not particularly strong. Gov. Tim Walz (D-MN), the Democrats’ 2024 vice presidential nominee who could seek a third term, is not immensely formidable, but Republicans have really struggled to break through in recent statewide elections there. In open New Mexico, former Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland (D) is by far the most prominent candidate on either side.

— One other wrinkle of this year’s races that we wanted to mention is that while the normal trajectory for politicians is to first win a governorship and then move to the Senate, a trio of senators appear likely to try to make the opposite move. Sens. Michael Bennet (D-CO), Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), and Tommy Tuberville (R-AL) all could try to move from the Senate to their state’s respective open-seat governorship (we rate all of these states as safe for the incumbent party). Bennet has already announced, and recent reporting indicates Blackburn and Tuberville could soon. Such a move would hardly be unprecedented, though: just last year, now-Gov. Mike Braun (R-IN) moved from the Senate to a governorship.

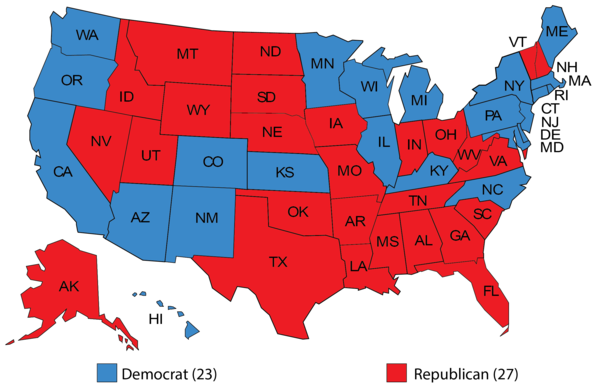

Overall, Republicans have 27 governorships and Democrats have 23. Map 2 shows the current breakdown.

Map 2: Current party control of governorships

Of the races up in 2026, the playing field is exactly split: Democrats and Republicans are both defending 18 governorships apiece. It’s 19 apiece if we include Democratic-held New Jersey and Republican-held Virginia in 2025. Despite an overall political environment that should favor them to at least some degree next year, Democrats start off slightly more exposed, as they are the ones defending the two Toss-ups, Arizona and Michigan, while both sides start as a favorite to flip a single state from the other (Democrats in Virginia in 2025, and Republicans in Kansas in 2026). But because of the high number of open seats, we think it’s possible that some of the Likely-rated states—or maybe even one of the Safe-rated ones—will develop into real contests next year.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.