Georgia Senate Runoffs: Breaking Down November, Looking to January

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman and Niles Francis

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— In a highly unusual situation, both of Georgia’s Senate seats will be on the ballot next month — one seat was already scheduled to be elected, while the other is a special election.

— As January’s result will decide control of the Senate, both sides are invested in Georgia’s outcome.

— In the regular election, Democrat Jon Ossoff made some gains in the suburbs since he was last on the ballot, but to beat Sen. David Perdue (R-GA), he’ll likely have to do even better.

— The battle for the state’s other seat is a bitter contest between appointed incumbent Kelly Loeffler (R-GA) and Rev. Raphael Warnock, a Democrat and a preacher.

— Though it would add an extra layer of chaos to the outcome, history — and data from November — seems to point away from a split outcome.

All eyes on Georgia

As the calendar year winds down, political observers still have two major elections to look forward to — on Jan. 5, Georgians will start off the year by voting in two Senate contests. While the fact that the Peach State is hosting these runoffs isn’t too much of a surprise, the stakes are.

Last month, Democrats underperformed expectations in key Senate races. They were burned in Maine and North Carolina, where their nominees had clear leads in both polling and fundraising, while they saw highly-touted challengers in redder states, like Montana and South Carolina, endure double-digit losses. Though Democrats ended up netting a seat, they’re projected to hold 48 seats to the GOP’s 50, while the two GOP-held Georgia seats will be decided next month.

Because of their disappointing results last month, Democrats’ only path to Senate control in the 117th Congress (barring a party switch or vacancy) would be to run the table on the two Georgia races. In that scenario, the Senate would be tied 50-50 and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris would cast a tiebreaking vote. If Republicans hold only one of Georgia’s seats, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) would retain a 51-seat majority. So no pressure, Georgia voters!

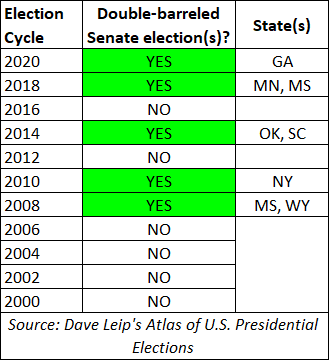

This type of double-barreled Senate election occurs with some regularity. Since 2000, five biennial election cycles have seen scenarios where both of a state’s Senate seats were up, while six cycles haven’t (Table 1).

Table 1: Double-barreled Senate races since 2000

But control of the chamber has never hinged on a double-barreled runoff.

Sen. David Perdue (R-GA) was first elected in 2014, and would have been scheduled to face voters this year regardless, with his standard six-year term expiring. His colleague, Sen. Kelly Loeffler (R-GA), was appointed last year to finish the term of former Sen. Johnny Isakson (R-GA), who retired early. Loeffler’s seat will come up again in 2022, so she — or her Democratic opponent, Rev. Raphael Warnock, if he wins — must be prepared to run again in two years for a full term (though either could, theoretically, serve two years and retire, leaving an open seat).

While both races are critical to the overall senatorial picture, the developments and trajectory of the regular election have been more straightforward, so let’s start by looking at that race.

Regular Election: Ossoff wins GA-6, but he’ll need to do even better

Last month, Sen. Perdue finished with 49.7%, while his Democratic challenger, Jon Ossoff, took a tick under 48% — the rest went to Libertarian Shane Hazel. As Georgia law states that no candidate can hold state office without winning a majority of the vote, the race advanced to a runoff. Indeed, Georgia is the only state that uses a standard partisan primary system but also requires general election runoffs. Historically, or at least since 2008, the runoffs have helped to insulate Republicans in statewide races, as Democratic enthusiasm tends to taper off after November — however, given the national implications, neither side is taking anything for granted this time

Broadly, the dynamic at the top of the ticket was similar to North Carolina, a demographically comparable southeastern state that saw closely-contested presidential and senatorial races. Though President-elect Joe Biden lost North Carolina by just over one percentage point, he did slightly better than the Democratic nominee, former state Sen. Cal Cunningham, who lost by 1.8%. In Georgia, Biden became the first Democrat since Bill Clinton in 1992 to carry the state, but not all the elements of his coalition transferred down the ballot.

To wit, Biden received almost exactly 100,000 more votes than Ossoff. That gap was most acute in precincts in the northern part of the Atlanta metro area. On one level, this wasn’t that shocking. Biden tended to earn the most votes, compared to Ossoff, in areas like northern Fulton County and southern Forsyth County — these areas have only started to shift Democratic fairly recently, and presidential voting trends often take longer to solidify down the ballot. Still, Ossoff is well known in the area, so his underperformance is something Democrats should take note of.

Before he was a senatorial candidate, Ossoff was the Democratic nominee in a 2017 special election in Georgia’s 6th District. Interestingly, GA-6 covers much of the area where he most underperformed Biden.

That June 2017 election was watched nationally, as an early test of Democratic resilience in the Trump era, and the winner would replace then-Secretary of Health and Human Services Tom Price, who had held office in the area since the 1990s. At the time, it was the most expensive congressional election in history; considering that over $400 million has been spent already on the Georgia runoffs, his current situation must seem like a familiar predicament to Ossoff. Though Republicans ended up holding the seat with former Georgia Secretary of State Karen Handel, their success was ephemeral — Handel rented the seat for about 18 months before losing to now-Rep. Lucy McBath (D, GA-6).

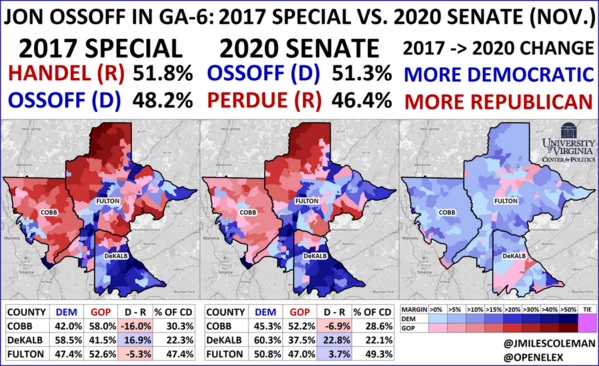

In 2017, Ossoff lost what, at the time, must have been a stinging 52%-48% race to Handel. But this year, he considerably improved his standing in GA-6, carrying it by five percentage points (Map 1).

Map 1: GA-6, 2017 vs. 2020

As the third image in Map 1 shows, Ossoff improved throughout much of the district. About half of the district is based in northern Fulton County — it includes municipalities such as Alpharetta, Johns Creek, and Roswell. Handel carried this area by over 5% in 2017, but that portion of the district backed Ossoff 51%-47% this year. To the west, Cobb County acts as the GOP bastion in GA-6, but Perdue’s 7% margin there was a significant drop from Handel’s 16%. On the other extreme of the district, both geographically and ideologically, the DeKalb County portion gave Ossoff double-digit margins both times, though there was some notable internal movement.

On the third image in Map 1, there’s a salient pink strip that bisects DeKalb County — these precincts all got more Republican from 2017, and one of them, in Brookhaven, even flipped against Ossoff this year. Perhaps not surprisingly, most of these precincts have relatively high Hispanic populations, a group that, across the board, swung to Trump in 2020. According to Dave’s Redistricting App, those precincts in DeKalb County that swung against Ossoff were 46% Hispanic by total population as of the 2010 census, and that number has likely gone up. Though the Georgia runoffs have very much the feel of a special election — which can lead to, well, special, results — perhaps January’s results will show how much of Trump’s Hispanic strength will transfer to other Republicans in his absence from the ballot.

While Ossoff’s performance in GA-6 represented a solid reversal of his 2017 showing, it wasn’t the best Democrats could do there. In the presidential race, Biden carried the district by nearly a dozen percentage points. Biden’s victory in Georgia gives Democrats the blueprints of what a statewide victory looks like, so increasing his margin in GA-6 will be paramount for Ossoff in the runoff.

Special election: Out of the jungle, into the runoff

In contrast to the regular race — which has been in a general election mode since the summer — the special election matchup was only solidified last month. Perhaps because this race has been so fluid, it’s made for a more dynamic campaign to follow.

The genesis of this unusual election was in August 2019. Capitol Hill’s — and Georgia’s — political atmosphere was rattled by the news of Sen. Johnny Isakson’s (R-GA) resignation. Isakson, a Republican who was elected to the Senate in 2004, cited his ongoing battle with Parkinson’s Disease. His departure left Gov. Brian Kemp, also a Republican, with the responsibility of naming his successor in the Senate.

President Donald Trump personally lobbied Kemp to appoint Rep. Doug Collins (R, GA-9) to the seat. Collins, with his political base in the Appalachian north, was one of the president’s most vocal defenders during the impeachment proceedings. Instead, Kemp chose to appoint wealthy Atlanta businesswoman Kelly Loeffler. A financial executive, Loeffler owns part of Atlanta’s Women’s National Basketball Association team and is married to Jeffrey Sprecher, the president of the New York Stock Exchange. The thinking seemed to be that Loeffler would be better-positioned to appeal to women in the state’s fast-growing suburbs — and after all, Sen. Perdue, as a first-time candidate in 2014, successfully swapped his career as an international business executive for an assignment in the U.S. Senate.

After being snubbed for the appointment, Collins expressed interest in running for the seat and formally entered the race in January 2020. He had the support of some Tea Party-aligned groups, who expressed concerns about Loeffler’s conservative credentials. Collins would also eventually garner several legislative endorsements, including from state House Speaker David Ralston (R). His early supporters charged that Loeffler has made campaign donations to Democratic politicians in the past and that the WNBA has ties to abortion rights group Planned Parenthood.

Given Georgia’s federal trends, Democrats vowed to make a serious play for this seat, and they rallied around Rev. Raphael Warnock, the pastor of Atlanta’s historic Ebenezer Baptist Church (the late Martin Luther King Jr. was ordained and preached there). He received early endorsements from 2018 gubernatorial nominee Stacey Abrams, the late Rep. John Lewis (D, GA-5), and the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC). Other Democrats attempted to compete in the race as well, but they were either poorly-funded or had support that was too regionalized.

In Georgia, special elections are held under Louisiana-style jungle primary rules. This means that every candidate, regardless of their party affiliation, appears on the same ballot, with the top-two finishers advancing to a runoff if no one gets over 50% (this same format led to the Ossoff vs. Handel special election runoff in 2017). As the race featured 20 candidates (though not all of which were serious), a runoff was essentially guaranteed. In a late October ad, Warnock found a creative way to emphasize his place in the crowded field: He reminded voters to “look all the way down there” for his name on an alphabetically-listed ballot.

For the earlier months of the campaign, most of the attention was centered around the battle between Collins and Loeffler — some polls even suggested an eventual intraparty GOP runoff.

In the early weeks of the coronavirus pandemic, Loeffler came under fire for some stock transactions that she and her husband made after she attended a briefing on the threat of the virus. Documents revealed that she and her husband sold stock in companies that were likely going to be hit the hardest by the pandemic. She denied any wrongdoing and was cleared by the Department of Justice. But accusations of insider trading still figured prominently into attacks on her, by both Collins and Democrats. (Perdue has dealt with similar attacks in the other Senate race.)

To recover, the Loeffler campaign adopted a seemingly counterintuitive strategy, given the rationale behind her appointment, but one that paid off against Collins: She ran to his right. In one ad, the senator who was purportedly appointed to appeal to soft suburban Republicans claimed to be “more conservative than Attila the Hun.” On the campaign trail, she welcomed an endorsement from Rep.-elect Marjorie Taylor Greene (R, GA-14), a far-right Republican who has associated herself with the debunked QAnon conspiracy theory.

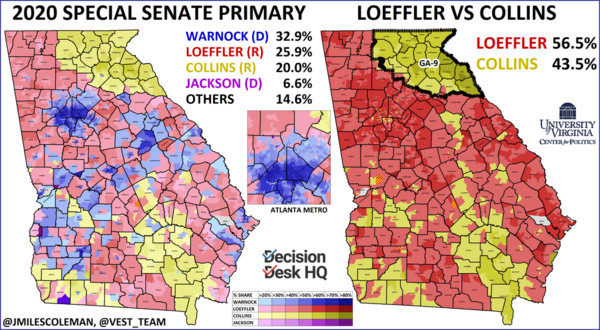

Loeffler’s maneuvering proved to be successful, at least in making the runoff: She took second to Warnock, and finished six percentage points ahead of Collins (Map 2).

Map 2: 2020 Georgia special Senate primary

GA-9 is outlined in the right image on Map 2 — Collins carried nearly every precinct in his northeastern home district, and according to calculations from Daily Kos Elections, took a healthy 45% plurality there. Still, there are some visual signs that Loeffler’s support from Greene may have paid off. Collins’ strength, at least in the northern part of the state, was essentially coterminous with the 9th District’s borders. Greene’s district, GA-14, makes up the northwestern corner of the state — Loeffler dominated there, creating a clean geographic rift in northern Georgia.

As Republican partisans had a choice between two well-financed conservatives, national Democrats didn’t invest a lot of resources in the jungle primary. Warnock’s campaign got off to a slow start, and he had to deal with some unpleasant headlines himself. For instance, a few weeks after he entered the race, he and his wife of three years were in court attempting to resolve a divorce dispute. He also had trouble picking up name recognition early on — during the summer, some polling showed him struggling to garner 10% support. But his campaign began to take off in early fall after he received an endorsement from former President Barack Obama and started airing television ads. For Warnock, it seemed to be a case of peaking at the right time; as he consolidated the Black vote, he climbed to first place in Monmouth University’s final poll and earned a spot in the runoff.

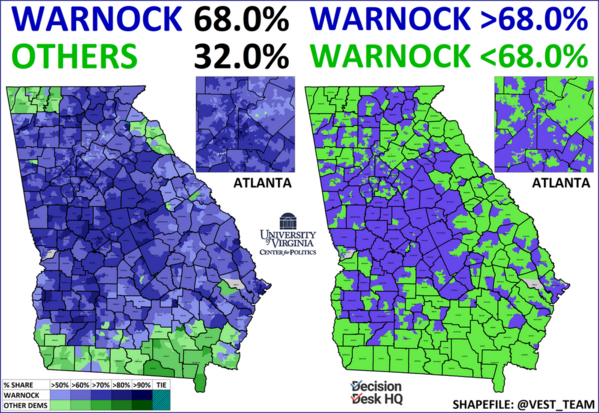

Warnock had the Democratic “lane” of the jungle primary largely, but not entirely, to himself. While no other candidates that shared his party label claimed double-digit support, he still was on the ballot with seven other Democrats. Map 3 considers only the votes that Democrats received in the jungle primary. Warnock’s 1.62 million votes represented 68% of the 2.38 million votes that the Democratic field received.

Map 3: Warnock’s share of the Democratic vote

To a large extent, these maps line up with the state’s media markets. Warnock ran especially well in the Atlanta and Macon areas, and he took a share greater than his statewide 68% in those areas. On the left map, the five green counties in the northwest are all in the Chattanooga, TN media market. Similarly, to advertise in the state’s southern tier of counties, candidates must book ads in Florida metro areas.

Warnock ran well in Chatham County — he’s originally from its largest city, Savannah, and was above 68% in many of its precincts, so perhaps he saw something of a hometown boost. Though by the same token, in another non-Atlanta metro, Augusta, he fell below his state average. One of his Democratic opponents, former state Sen. Ed Tarver, is from the area. Statewide, Tarver took just 1% of the Democratic vote, but 12% in Augusta’s Richmond County.

In the Atlanta area, Warnock was relatively weak in Gwinnett County, an area that has fueled recent Democratic gains in the state. In the central part of the county, which runs along a stretch of Interstate 85, he was only polling in the 50s (sticking to the left image on Map 3). In the 2018 Secretary of State runoff, Gwinnett was one of the counties most responsible for sinking the Democratic nominee, former Rep. John Barrow (D, GA-12) — in a December runoff, he fared much worse than Stacey Abrams did in her gubernatorial race the month before. This isn’t to say that the county will see a similar drop-off next month, but it’s a place where Democrats have lost votes in the past.

Overall, the runoff election is shaping up to be very contentious. Warnock has attacked Loeffler for trading stock as the pandemic was crippling the economy. Loeffler has tried to frame some of Warnock’s lines from past sermons as extreme, and has accused him of wanting to defund the police. The sole debate of the runoff was defined by these attacks. Loeffler repeatedly called Warnock a “radical liberal” while he countered that she was “appointed, and Georgia has been disappointed.” Though that debate was predictable, and almost seemed scripted, at least voters got a fresh taste of their options together — in the runoff for the regular election, Perdue skipped a debate with Ossoff.

For partisans, runoff elections are often about turning out the base — the venues where each candidate has campaigned illustrate this well. For their part, Republicans are working to turn out rural areas: Loeffler kicked off the start of the early voting period this week with an event in Rome, in the northwestern corner of the state, while Perdue rallied in Macon, an area where his political family has its roots. On the Democratic side, Biden headlined a drive-in rally in Atlanta this week, though Democrats are also hitting other metro areas. Ossoff recently appeared in Augusta, an region where Biden made some notable gains over past Democratic presidential nominees.

The bottom line: This election is about as close as you can get. In November, polling-based aggregates were relatively accurate in Georgia — FiveThirtyEight’s model, for instance, pointed to a narrow Biden win — and the polling we’ve had since then of the Senate races usually finds the contests within the margin of error. It’s hard to tell who has the edge, but undoubtedly, the party that does a better job turning out the base will be the party that carries the day.

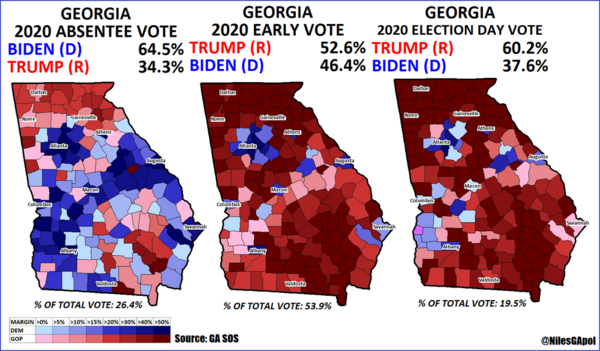

Early voting seems to be off to a strong start — though given the odd timing of this election, it is possible that early voting may be a bit frontloaded, as voters may want to get their civic duty out of the way before the holidays. Going into the November election, Democrats relied most on absentee voting by mail. The early in-person vote — which accounted for 54% of the overall total — favored Trump, but not as heavily as what was cast on Election Day (Map 4).

Map 4: November 2020 Georgia vote by method

P.S. History is against a split verdict

Almost exactly three years ago, with the 2018 midterms approaching, former Crystal Ball associate editor Geoffrey Skelley took an extensive look at the history of double-barreled Senate elections. One of the article’s key findings was that the last time a double-barreled situation resulted in a split senatorial delegation was back in 1966. So, in other words, in these types of scenarios, both seats almost always go to one party. A precinct-level analysis of November’s Georgia elections seems to suggest this pattern will continue.

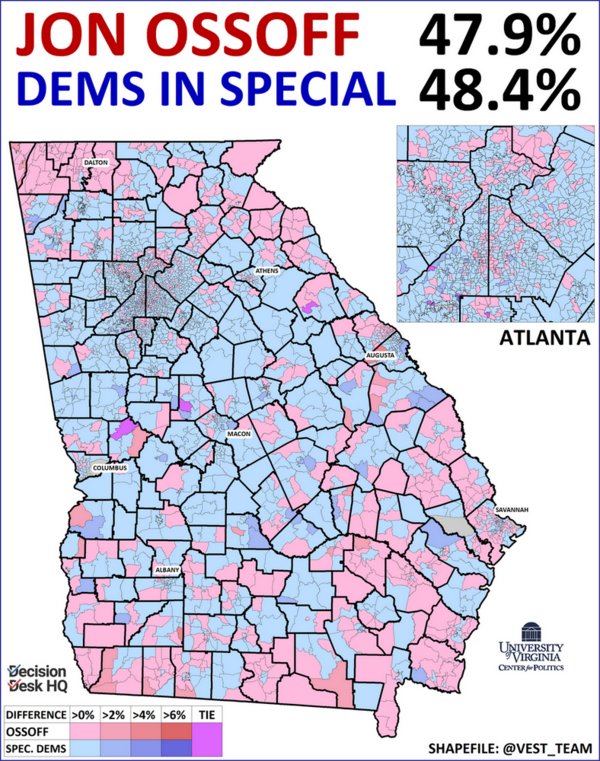

Map 5 compares the 47.9% share that Ossoff received against Perdue to the 48.4% that the Democratic candidates in the special election combined for. Ossoff ran ahead of the Democratic share in the special election in the red precincts, and behind in blue.

Map 5: Ossoff vs. Democrats in the special election

What should stand out most about Map 5 is its simplicity: almost every precinct is the lightest shade of red or blue. So even down to the local level, Ossoff’s share tracked very closely with that of the Democratic aggregate in the special. In over 90% of the state’s nearly 2,700 precincts, the two shares were within 2% either way. By contrast, the variance between the presidential and senatorial races tended to be greater — in some parts of the Atlanta metro area, it wasn’t uncommon for Biden to poll 5% or higher than Ossoff.

While there will inevitably be some voters who split their tickets — perhaps in the interest of fostering a split government, or they may genuinely like candidates from different parties — given the highly partisan and nationalized tenor of the campaign, one party seems likely to monopolize the results.

Democratic sources have stressed to us for months that Ossoff and Warnock have very much tried to run as a ticket — even before the November election, they held several joint events. On the GOP side, Collins was a team player: He immediately endorsed Loeffler after the primary. So, going into an election where the stakes couldn’t be higher, both parties are working to project images of unity.

However, Map 5 also suggests a key fact to remember: Even as Biden was narrowly winning Georgia in November, Perdue and the combined Republican vote outpaced Ossoff and the combined Democratic vote in both Senate races. If the Republicans hold both Senate seats, this dynamic from the first round of voting may have been prophetic.

The Crystal Ball continues to rate both races as Toss-ups.

J. Miles Coleman is associate editor of Sabato’s Crystal Ball.

Niles Francis is an election analyst from Atlanta who covers races for the elections reporting organization Decision Desk HQ. His Twitter handle is @NilesGApol.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.