How Virginia Illustrates the 2024 Election

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Kamala Harris carried Virginia by close to 6 points this month. This was worse than Joe Biden’s 10-point showing in the state, although it was slightly better than Hillary Clinton’s performance, even as the latter had a Virginian (Sen. Tim Kaine) on her ticket.

— Much of the state’s movement to Donald Trump can be attributed to a pronounced rightward shift in heavily Democratic Northern Virginia.

— Though she lost ground overall, Harris held on to some of Joe Biden’s 2020 gains in many of the state’s more marginal localities.

— Though it was not a Toss-up state, in some ways, such as its internal swing and voting rhythms, Virginia was in sync with the nation as a whole.

Virginia in 2024

On Election Night, most of the Crystal Ball team—namely, myself and Managing Editor Kyle Kondik—was in Manhattan covering the returns with CBS News. Though we were tasked primarily with following House returns, we, of course, tried to keep tabs on the presidential situation—considering the nationalization that has characterized recent elections, down-ballot races have become increasingly correlated with presidential returns anyway.

Not long into the evening, Florida, a state with an early poll closing time that tends to tabulate its returns quickly, had posted a critical mass of votes. Trump seemed to be doing well in the Orlando area’s heavily Puerto Rican Osceola County, although Rep. Darren Soto (D, FL-9) appeared on track for reelection. While Trump’s strength in this type of area seemed to go against some narratives that had taken hold in the last week or so of the election, we figured, “eh, this might just be Florida being Florida.” Given the topline movement in the area, Soto may emerge as a more attractive GOP target in future cycles, but at the presidential level, Florida is a red-trending state that got little attention this year—so, surely, it wouldn’t be very representative of other places, right?

Then Virginia began reporting.

The result in Loudoun County, one of those suburban counties that was marginal in Barack Obama’s races but had moved sharply left in more recent elections, made the tea leaves out of Florida harder to dismiss. With most of its returns in, Kamala Harris was running several points behind Joe Biden’s 2020 margin. To us, this was confirmation that things were starting to go awry for Harris.

With our home state playing an important role in setting the tone for the rest of the election, we are going to take a deeper look at how Virginia voted earlier this month.

Before we move on, though, we’d note that while the state’s returns are almost complete, they are not official. As usual, we’ve tried to be duly diligent when calculating some granular results that will come up later, but they could still change slightly.

At the topline level, Harris carried the state by a little less than a 52%-46% margin over Trump, making her showing in the state closer to Hillary Clinton’s 5.3-point margin in the state than Joe Biden’s margin of barely over 10 points.

Despite the overall decline, Harris held on to most of Biden’s gains, at least when it came to carrying localities. Two significant localities that Biden flipped in 2020 were Chesterfield County (south of Richmond) and James City County (next to Williamsburg, it is home to the famous colonial Jamestown settlement). Harris expanded on Biden’s margins in both; in fact, unlike in 2020, both localities were more Democratic than the state as a whole this year. Going north and east, respectively, Stafford County, an area that is filling up with workers who commute into Northern Virginia, plus Virginia Beach and Chesapeake, in the southeast, were Trump-to-Biden localities that Harris held, if by reduced margins.

The only locality that voted for Trump in 2016, against him in 2020, and then returned to his side was Lynchburg (home of the evangelical Liberty University). Meanwhile, Surry County, a small southeastern county, and Prince Edward County (a Southside locality that includes Longwood University, which got some national attention in 2016 as the scene of a vice presidential debate) flipped to Trump after voting against him twice.

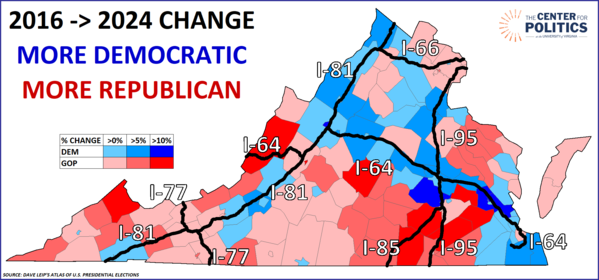

Map 1 compares Harris’s margin in the state, nearly 6 points, to Hillary Clinton’s from 2016 (again, a slightly lesser 5.3-point win). Map 1 also overlays the state’s major interstate highways on top of the partisan swing by county.

Map 1: Virginia 2016 vs. 2024

Perhaps the 2016 to 2024 swing in Virginia could be summed up by saying that the longer highways (64, 81, and 95) got bluer, while the shorter ones (66, 77, and 85) got redder.

Cutting horizontally across the state, I-64 runs through, or at least approaches, the localities that have swung most Democratic. Starting in the east near Virginia Beach, it runs west to connect the Williamsburg area to the Richmond metro (which, respectively, includes the aforementioned James City and Chesterfield counties), then follows a streak of blue localities including Charlottesville and Staunton. Virginia’s fastest-growing county, New Kent, is also in this corridor, bridging the Richmond and Williamsburg areas.

In southwest Virginia, I-81 begins in Bristol, runs up to the Roanoke area, and then goes into the Shenandoah Valley; each of those areas got at least a little bluer since 2016. Although the southern part of I-95 runs through some red-trending Southside localities that have not seen much economic growth in recent decades, the aforementioned Stafford County is typical of several of its northern localities.

Going south, I-77 and I-85 briefly cut through either side of the state. I-77 includes parts of Appalachia while I-85 runs through a couple of Southside localities. Both stretches are almost entirely rural and have reddened since 2016.

In Northern Virginia, I-66 is another relatively short interstate that passes through some red-moving localities.

Whoa, wait! So this suggests that Northern Virginia, the Democratic bastion of the state, got more… Republican?

Yes, and in fact, that movement is even more striking when we use 2020 as a baseline year.

The localities that make up Northern Virginia—we are using a somewhat conservative definition by calling Loudoun County its western border and Prince William County its southern border—collectively swung 8 percentage points rightward. That swing is basically commensurate with what we first saw in Loudoun County on Election Night. Overall, Harris’s 64%-32% margin in the region was down from Biden’s 69%-29% (as Map 1 also implied, Harris’s margin there was also slightly down from Clinton’s 64%-30%). Meanwhile, the rest of the state, which cast about 70% of Virginia’s total vote, saw a less drastic shift. In 2020, Trump carried the rest of the state by 2 points, and upped that advantage to just under 5 points, accounting for a 2.7-point improvement.

So Virginia was representative of the nation in that Northern Virginia, usually considered its Democratic stronghold, swung Republican more than the nation as a whole did (such was the case in deep blue states like Illinois and New York), while the balance of the state, which is more marginal, saw a smaller shift that was comparable to competitive states like Georgia and North Carolina.

Put a little differently, the pro-Trump swing was not very efficiently distributed throughout the state for Republicans. The biggest Trump gains came in either deep blue Northern Virginia or in several depopulating Southside localities that have been reddening for some time. Meanwhile, Harris held up much better in the competitive areas of the state. For instance, according to Chaz Nuttycombe, a Virginia-based analyst and President of State Navigate, Harris actually carried 25 seats in the state Senate, up from Biden’s 24 (the flip was in the Chesterfield County-centric SD-12).

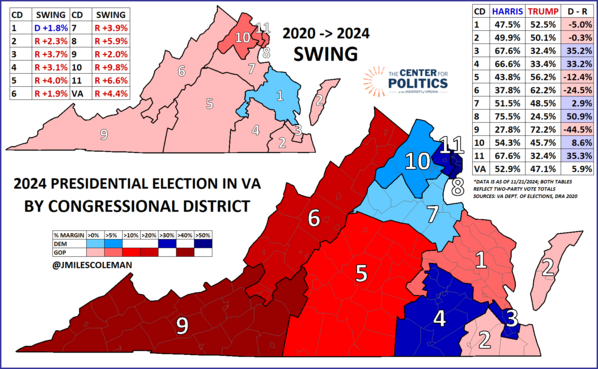

Map 2 shows how this plays out in the context of the House map.

Map 2: 2024 in Virginia by congressional district

In Northern Virginia, three districts swung more than 5 percentage points to Trump. While this was hardly enough to imperil Reps. Don Beyer (D, VA-8) and Gerry Connolly (D, VA-11), the area’s redshift did mean a closer-than-expected result for Rep.-elect Suhas Subramanyam (D, VA-10). Our thinking was that Subramanyam, who held an open seat, would improve on outgoing Rep. Jennifer Wexton’s (D) 53%-47% margin from 2022. Instead, as the Democratic margin dropped nearly 10 points from 2020 at the presidential level, the House result there this year was even closer than what 2022 saw.

In retrospect, Wexton’s 6-point win in a double-digit Biden seat actually looks like less of a blip and seems to fit into a multi-cycle pattern. In 2023, Democratic candidates took just over 52% of the popular vote for both the state Senate and House of Delegates in the precincts that make up VA-10. That is also exactly where Subramanyam ended up this year. While the area could get bluer again now that Republicans will be the presidential party (Virginia often reacts against the party in the White House), this will be a place to watch going forward. For more on how 2022 and 2023 informed 2024 results in places like Virginia, we would recommend this two-part report by friend of the Crystal Ball Sean Trende.

Outside of Northern Virginia, most districts got more Republican, but only slightly so. In the Virginia Beach area, Rep. Jen Kiggans (R, VA-2) won a second term by a 51%-47% margin, continuing her district’s 16-year streak of sending a member of the majority party to the House. Going into the election, Kiggans was the delegation’s sole “crossover” member (she was a Republican in a Biden-won seat) and she very nearly remained one. District 2, a Biden +2 seat, apparently flipped to Trump, but just barely: according to our calculations, Trump would have carried it by about 1,000 votes out of the nearly 410,000 it cast. District 7, the only other Virginia seat that saw general election spending by big outside groups, remained a marginal Democratic seat. As Harris carried the seat by 3 points, down from Biden’s high single-digit showing, Eugene Vindman (D) won this open seat by 2 points. (These figures are slightly different than ones cited in the Crystal Ball last week because the election returns are now more complete.)

The 1st District, held by the long-serving Rep. Rob Wittman (R), was the only district that bucked the prevailing trend, giving Harris a better showing than Biden, although Trump still carried it by 5 points. While VA-1 is, visually, a district that takes in wide swaths of the Tidewater region, it includes many of those I-64 localities that we mentioned earlier. Wittman, who has frequently been mentioned as a statewide candidate but has never taken the plunge, typically outperforms the top of the ticket—he ran more than 7 points better than Trump in his district this month—but he has also never really faced what we’d consider a top-tier Democratic challenger.

We would also note that VA-1 cast the most votes of Virginia’s districts. Harris and Trump combined to claim nearly 478,000 votes in VA-1; our district, VA-5, took second place, with 437,000 between the major-party candidates. The current VA-1 and VA-5 would have kept their respective positions in 2020, although the gap has grown: VA-1 cast 25,000 more votes for the major-party candidates then, and just over 40,000 more this year.

While we are on the subject of turnout, it may be worth pointing out that (again, sticking to two-party totals) 7 of the 11 current districts cast more votes in 2024 than they would have in 2020. The only exceptions were the deep blue quartet of Districts 3, 4, 8, and 11 (3 and 4 are southeastern districts with sizeable Black populations while 8 and 11 are in Northern Virginia). So while Democrats may have held up relatively well in swingier areas of the state, the turnout drop in these districts may speak to some weakness with their base voters.

Finally, on more of a national level, one of the surprising results this year was the degree to which Republicans embraced early voting. In previous cycles, perhaps taking cues from Trump, Republicans were generally more skeptical of early and absentee voting. But Virginia’s 2023 legislative elections proved to be a canary in the coal mine.

In 2020, Biden carried the combined absentee vote (early in-person and mail-in) by 31 points while Trump won the Election Day vote by 26 points. Biden had the advantage because only 37% of votes that year were cast on Election Day.

But during Virginia’s 2023 legislative elections, Gov. Glenn Youngkin (R) implored Republicans to vote before Election Day. The result of Youngkin’s efforts, likely coupled with the fact that the receding pandemic made absentee voting less of a necessity to voters generally, was a bluer Election Day vote. Across most key legislative races, Election Day voters skewed more Republican than other voters, but hardly to the extent that they did in 2020.

This month, Virginia looked more like 2023 than 2020, in that there was less of a partisan chasm between voting methods. According to breakdowns provided by the Virginia Department of Elections, about 46% of the vote was cast on Election Day—while Trump won those voters, he only did so by 6 points. Meanwhile, Harris carried the rest of the electorate (mostly early in-person and mail-in voters) by about 15 points.

So Virginia’s voting rhythms have very much been in flux over the past few years—this is due in part to the pandemic, as well as some recent legal changes. In 2020, Democrats, who then had a trifecta, made absentee voting more accessible, and these changes also happened to coincide with the pandemic, when many voters were looking for options aside from going in-person on Election Day. As part of the Democrats’ reforms, same-day registration became operative for 2022. In elections since, ballots cast by same-day registrants have been counted as provisional ballots. Because of this, and as an illustration of how fluid the picture has been in recent years, in 2020, about 21,000 provisional ballots were cast in the presidential election—that was up to 115,000 this year.

With the presidential election over, Virginia will move closer to the center of the political universe next year, as our gubernatorial race has taken shape. While we’ll probably dig deeper into some of the state’s 2024 returns as next year’s election approaches, for now, we’ve tried to highlight several Virginia-specific trends to keep an eye on.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.