Stepping Up: How Governors Who Have Succeeded to the Top Job Have Performed Over the Years

A Commentary by Geoffrey Skelley

2018 could see a number of successor governors running for full terms in office

On Monday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) moved to end debate on the nomination of Gov. Terry Branstad (R-IA) as the next U.S. ambassador to China. While the exact timeline is uncertain — Democrats could try to stall the appointment — Branstad’s confirmation for the diplomatic post is expected very soon. Upon becoming ambassador, Branstad will resign the Hawkeye State governorship and hand the reins over to Lt. Gov. Kim Reynolds (R), who will become Iowa’s first woman governor. Once she takes office, Reynolds is expected to run for a full term in 2018 as a gubernatorial incumbent, albeit a “successor incumbent” rather than an elected one.

She is unlikely to be the only such incumbent running in 2018. As things stand, there are already two freshly-minted governors who may fit the bill: Govs. Kay Ivey (R-AL) and Henry McMaster (R-SC) are already ensconced in their new posts due to the resignation of Gov. Robert Bentley (R-AL) and the appointment of former Gov. Nikki Haley (R-SC) as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. Ivey has not yet stated her plans regarding the 2018 election, but it would somewhat surprising if she didn’t run. After all, she ran in the 2010 gubernatorial race for a time before dropping down to run for lieutenant governor instead. McMaster is certain to run in 2018.

Additionally, it is possible that Lt. Gov. Jeff Colyer (R-KS), a possible 2018 gubernatorial candidate, could become governor of Kansas if Gov. Sam Brownback (R-KS) exits office early. In March, Brownback was rumored to be in line to become U.S. ambassador to the United Nations for food and agriculture. While there has been nothing further on his prospects for that appointment, Brownback’s name is now circulating as a possible choice to be the State Department’s ambassador for international religious freedom.

So there’s a chance that four (or even more) unelected gubernatorial incumbents could be on the ballot running for full gubernatorial terms next year.

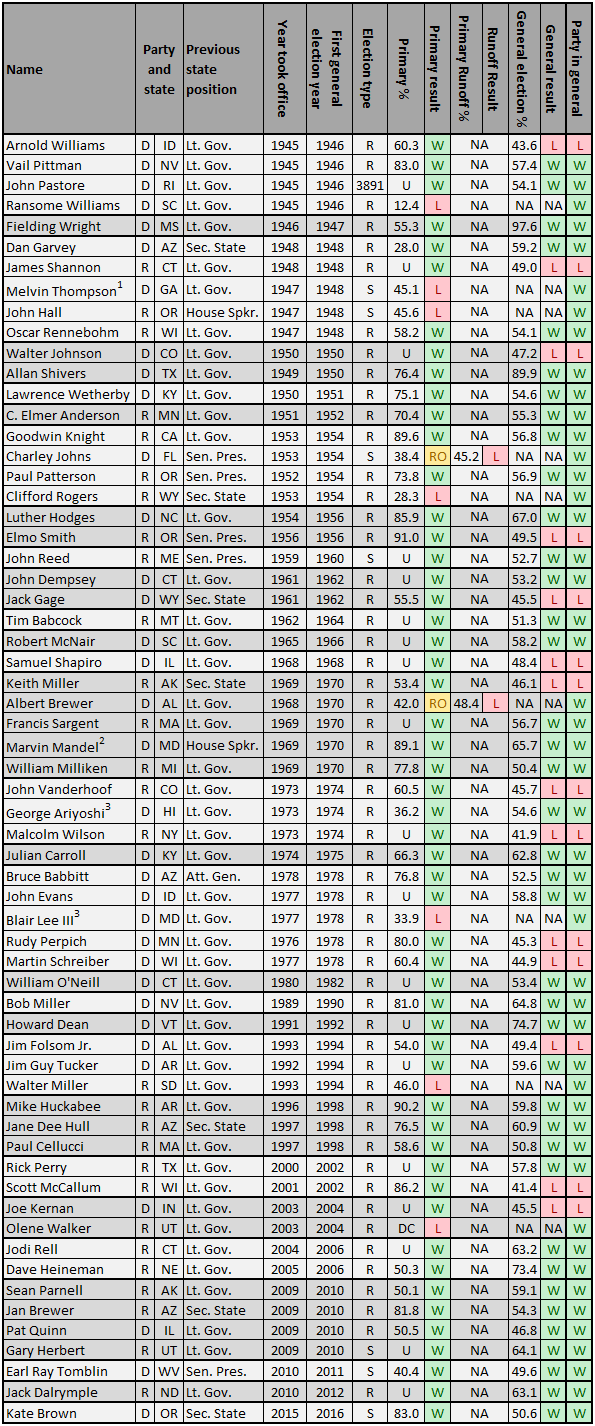

With at least a handful of successor incumbents or potential ones running for governorships in 2018, we decided to examine the electoral performances of previous governors who took office via succession going back to the end of the Second World War (i.e. first election is 1946). We looked at the primary and general election showings of every governor who ascended to that post following the resignation or death of the previous governor and then ran as a successor incumbent in the next regular or special election for that governorship.

As it turns out, having a sizable number of elections involving successor incumbents in 2018 wouldn’t be that unusual. Since the first post-World War II cycle in 1946, there have been nine election cycles (presidential or midterm) with at least three successor incumbent governors seeking election. In fact, there were five such contests in 1948, 1970, and 1978, and four in 1946, 1954, and 2010. Overall, 62 successor incumbents have sought to continue on as governor in the next regular or special election for the governorship, and they are listed in Table 1 below. This table includes two less-clear-cut cases who were serving as acting governors while the sitting governors were still technically in office, but they are included because they were serving in the gubernatorial role while actively running for the office (see the Table 1 footnotes). Most recently, then-Oregon Secretary of State Kate Brown (D) ascended to the governorship after the resignation of Gov. John Kitzhaber (D-OR) in 2015 and won the rest of that term in a 2016 special election; she will be up for a full term in 2018.

Table 1: Post-World War II successor gubernatorial incumbents who sought the governorship in next regular or special election

Notes: Instances where an individual succeeded to the governorship after losing a party primary for the ensuing election are not included. In the “Election type” column, “R” refers to a regular general election and “S” refers to a special general election. In the “Primary %” column, “U” signifies that the individual was unopposed in the party primary or was nominated at a party convention with or without opposition; “DC” signifies that the individual was defeated at a party convention. In the result columns, “W” indicates the individual won the primary, primary runoff, or general election; “RO” indicates that the primary election resulted in a primary runoff election; and “L” indicates that the individual lost in the primary, primary runoff, or general election. The “Party in general” column refers to the general election outcome for the successor incumbent’s political party. The data are available in spreadsheet form here.

Footnotes: 1.) Following the Three Governors Controversy, Lt. Gov. Melvin Thompson (D-GA) became governor of Georgia in March 1947. 2.) Following the election of Gov. Spiro Agnew (R-MD) to the vice presidency of the United States, state House Speaker Marvin Mandel (D-MD) was elected by the Maryland legislature to the governorship in 1969 because Maryland did not have a lieutenant governor position at that time. 3.) Lt. Gov. George Ariyoshi (D-HI) became acting governor in late 1973 because of the illness of Gov. John Burns (D-HI). Ariyoshi served in that role for the remainder of Burns’ term while running for governor in 1974. Lt. Gov. Blair Lee III (D-MD) became acting governor in the middle of 1977, when Mandel handed over executive power after being convicted for political corruption. Lee served as acting governor for 19 months and sought his party’s nomination in 1978 while in that position.

Sources: CQ Guide to Elections, OurCampaigns, Center for the American Governor, Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections, state election authorities, archived state blue books, and state legislative manuals

In total, 39 of the 62 successor incumbents who sought election from 1946 to the present went on to win the general election, 14 lost in the general election, and nine failed to win their party’s nomination. That 63% success rate is worse than the reelection rate of elected incumbent governors in the same timespan (74%) but does compare favorably to the 49% success rate of appointed U.S. senators who sought election since World War II. The better performance of successor incumbent governors versus appointed U.S. senators makes sense: Often times, the gubernatorial successor was elected in his or her own right for another statewide office such as lieutenant governor or secretary of state, whereas some appointed senators have not won a previous statewide contest — or any kind of election at all, in some cases.

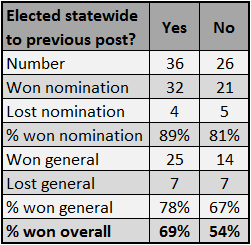

Unsurprisingly, gubernatorial successors who had previously won on their own statewide ballot line have performed slightly better than those who rose from top positions in state legislatures or unelected statewide offices. The latter category includes lieutenant governors who ran on the same ballot line as the governor; many states do not have separate elections for governor and lieutenant governor. Those who had won statewide before were more successful across the board, from nomination battles to general elections. Table 2 lays out the election data for successor incumbents for governor based on whether or not the individual had held a statewide-elected office prior to acceding to the governorship. Overall, 69% of successor incumbents who had been elected statewide to their prior position went on to win a gubernatorial general election versus just 54% of those whose previous post wasn’t a statewide-elected office. This pattern suggests that someone like Reynolds — a running mate — might be more vulnerable than someone like Ivey or McMaster, who were both elected in their own right as lieutenant governors (Ivey has actually won four statewide elections). Still, both Alabama and South Carolina use primary runoff systems, so neither will have a simple road to their party nominations.

Table 2: Successor incumbent gubernatorial election performance based on prior statewide elected status

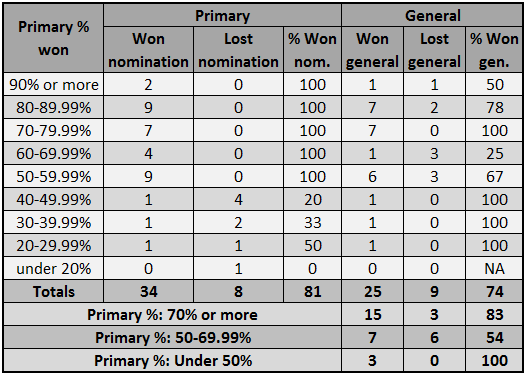

Turning more specifically to performance in nomination contests, 42 successor incumbents had primary opposition in the subsequent gubernatorial primary. They won an average of 62% of the vote and a median of 60%. But the primary vote percentage ranged from 12% to 91%. Table 3 lays out the primary and general election results for the 42 successor incumbents who faced primary opposition.

Table 3: Primary and general election outcomes based on primary performance

Note: Includes only the 42 successor incumbents who had opposition in their party primary. For candidates in runoff states, they are included based on their result in the initial primary.

With an eye on the general election, there does seem to be some connection between worse outcomes and greater competition in the primary. For successors who won 70% or more in their primaries, 83% won in November. But for those that won at least 50% but less than 70%, only 54% won in November. Of course, this is a small sample, and the three successors who managed to win their party nomination with less than 50% of the primary vote all went on to win in November. So don’t take it to the bank that winning less than 70% in a primary means a coin-flip in November for any of the 2018 successor incumbents. After all, Ivey and McMaster are both in deeply Republican states where winning the party primary/runoff may be tantamount to winning in November.

As for the nine successor incumbents who failed to get to the general election, their stories are possibly more interesting than those who won their party’s nomination. Of the nine, eight lost in primary or primary runoff elections and one at a party convention. Most of the primaries and primary runoffs were competitive, with only one successor governor losing by double digits (South Carolina’s Ransome Williams, who lost in the 1946 Democratic primary to a fellow named Strom Thurmond). Interestingly, in each of these nine cases, the loser’s party went on to win the general election. This was partly because some of the states were relatively safe for one party or the other (i.e. a Democratic Solid South state or a rock-ribbed Republican Plains or Mountain state).

A big-name intraparty opponent caused problems for some of these successors. Perhaps the best example was Gov. Albert Brewer (D-AL), who succeeded to Alabama’s governorship in 1968 following the death of Gov. Lurleen Wallace (D), wife of presidential aspirant and ex-Gov. George Wallace (D). Brewer then faced George Wallace in the 1970 Democratic primary for governor, winning a plurality of the vote, but not a majority. Wallace then narrowly edged Brewer in the primary runoff by three points and won the general election for the second of what would be his four terms as Alabama governor. South Dakota also had a former governor return to defeat a successor incumbent in 1994. Following the death of Gov. George S. Mickelson (R) in a plane crash, Gov. Walter Miller (R-SD) became chief executive of the Mount Rushmore State in 1993. But former Gov. Bill Janklow (R), who had served from 1979 to 1987, decided to run for the office again. The ex-governor defeated Miller by eight points in the party’s June 1994 primary and went on to win the general.

In a bizarre situation in Georgia, a former governor who had previously served for three months — Herman Talmadge (D) — defeated the “real” successor incumbent, Gov. Melvin Thompson (D), in the 1948 Democratic primary. Talmadge’s father, Eugene, won the Peach State’s 1946 gubernatorial election with nearly 99% of the vote, but the victor had been unwell for some time. Talmadge backers had worried about the possibility of the incoming governor dying prior to inauguration, leading them to get the younger Talmadge enough write-in votes to be a possible candidate for the state legislature to elect if the elder Talmadge passed away. Eugene Talmadge did die and his son, having finished second to his father by way of write-ins, was elected by the state legislature. However, the 1945 state constitution had created the post of lieutenant governor, which created confusion over succession. The lieutenant governor-elect, Thompson, eventually won in court to become the next governor, but not until Herman Talmadge had served as governor for three months. In the 1948 special election that followed, the younger Talmadge challenged Thompson in the Democratic primary for governor and defeated him 52%-45%, going on to easily win the general.

The lone successor incumbent to lose out at a party convention was Gov. Olene Walker (R-UT), who became the Beehive State’s first female governor in 2003 following the resignation of Gov. Mike Leavitt (R) to become EPA administrator. The long-time lieutenant governor was fairly moderate by Utah standards, and she decided to run for a full term only a couple of months before the party convention. She finished fourth at the conservative-dominated party convention in 2004, missing out on a top-two spot that would have placed her in the party primary (which Jon Huntsman went on to win).

So with all of this in mind, keep an eye on what the 2018 crop of successor incumbents decide to do and monitor just how strong their primary opposition may or may not be. They may start as favorites, but victory is no certainty.

Geoffrey Skelley is the Associate Editor at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

See Other Political Commentary by Geoffrey Skelley

See Other Political Commentary

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.