Governors 2016: Are We in for a Repeat of 2014’s Odd Results?

A Commentary By Larry J. Sabato, Kyle Kondik and Geoffrey Skelley

Democrats and Republicans are showing strength in some unexpected places

They aren’t getting much national attention because of the races for the presidency and Congress, but this year’s gubernatorial contests seem to be just as confounding as the ones from 2014 — and they could produce some equally head-scratching results.

Heading into Election Day 2014, polls in 11 of the 36 contested races showed a margin between the candidates of less than five percentage points, according to the HuffPost Pollster averages. These close races produced some results that cut against the partisan grain in many states: In a Republican-leaning year, states that typically vote very Democratic at the federal level like Illinois, Maryland, and Massachusetts elected Republican governors, and deep-red Alaska voted out a Republican incumbent in favor of an independent, Bill Walker, who had a Democratic running mate and was the de facto Democratic candidate.

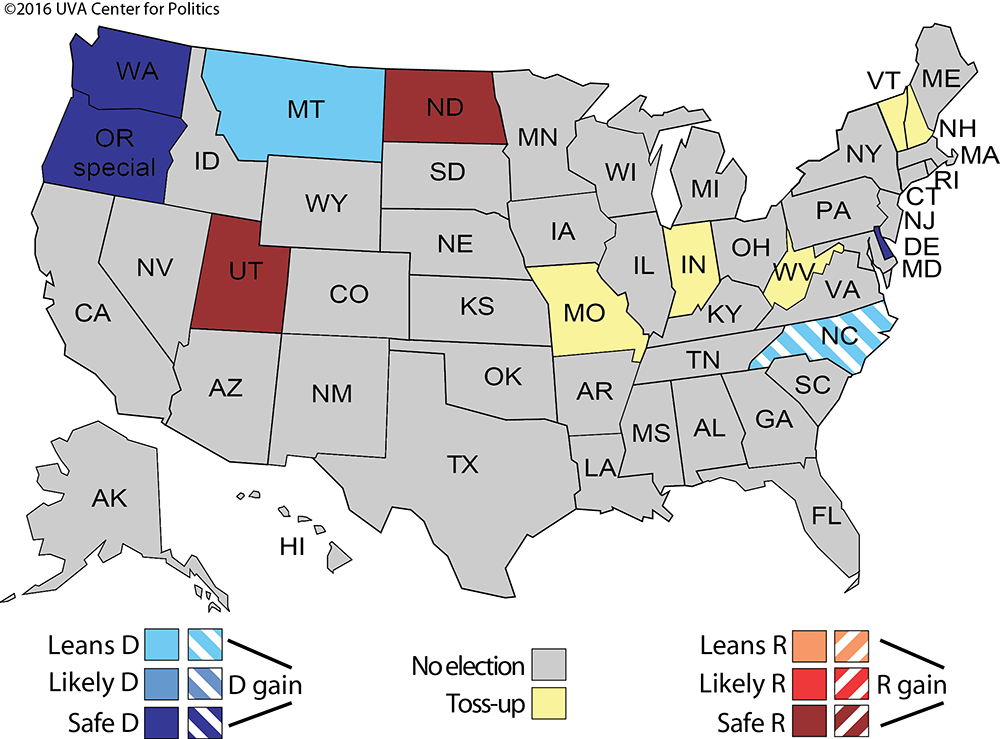

Most of the gubernatorial elections are held in the midterm year (and some others in odd-numbered years, like next year’s New Jersey and Virginia contests), but we have a dozen races this year, including a special election in Oregon. Of those 12 races, at least six appear to be very close: Indiana, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Vermont, and West Virginia. And another, Montana, is a potential dark horse. Map 1 shows our updated ratings and Table 1 presents each ratings change we’re making this week.

Map 1: Crystal Ball gubernatorial ratings

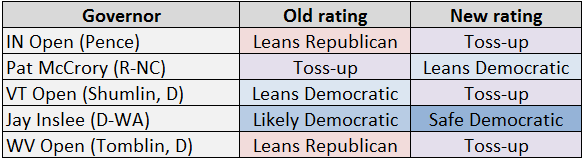

Table 1: Crystal Ball gubernatorial ratings changes

In fact, Vermont and West Virginia help illustrate how — even in a presidential year — a significant number of voters appear poised to split their tickets, at least between their federal vote and their state-level vote. They are also two states that help show the great changes that have taken place in American politics over the last few decades.

Crazy as it may sound to younger readers, Vermont was once one of the most reliably Republican presidential states in the Union. From 1856 — the first election to feature a Republican and a Democratic candidate, thus kicking off our durable two-party system — through 1988, the home of independent socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders voted Democratic for president exactly one time, in Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 blowout. By 2012, Vermont was Barack Obama’s second-best state, finishing only behind Hawaii (as well as the District of Columbia).

In 1988, while Vermont was narrowly supporting Republican George H.W. Bush for president, West Virginia was one of the handful of states that actually backed Democrat Michael Dukakis. From the dawn of the New Deal through Bill Clinton’s presidency, West Virginia was one of the most reliably Democratic states in the country, voting Republican only in big GOP national blowouts like 1956, 1972, and 1984 (the easy reelection years of Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan, respectively). But by 2012, West Virginia was Mitt Romney’s fifth-best state, and the state seems poised to vote very heavily for Donald Trump in the fall.

Despite these changes, both states still seem quite open to supporting their ancestral party, as opposed to the party they overwhelmingly back now, in their local gubernatorial race.

West Virginia hasn’t elected a Republican governor since 1996. In 2012, term-limited incumbent Earl Ray Tomblin ran 15 points ahead of Obama, winning by five points even as Obama was losing the state in a landslide. That same year, Sen. Joe Manchin (D) — a former governor — ran 25 points ahead of Obama.

While Vermont does have a Democratic governor — Peter Shumlin is not running for reelection to a fourth, two-year term — the state only very narrowly reelected the unpopular Shumlin in 2014: Thanks to a quirky law, the Democratic-controlled state legislature actually had to reelect Shumlin because the incumbent finished shy of an actual majority (despite winning a narrow plurality). And former Gov. Jim Douglas (R) won four, two-year terms from 2002-2008. In his final election, Douglas got 53%, easily beating an independent and a Democrat, and he ran 23 points ahead of Republican John McCain.

In West Virginia, Republicans are hoping to complete their recent transformation of state government. They won control of the state House and Senate for the first time since before the Great Depression in 2014, and they are hoping to take complete control by electing state Senate President Bill Cole (R) to the governorship. Standing in their way is Jim Justice, the state’s only billionaire and a nominal Democrat. Justice, a coal magnate, said he won’t support Hillary Clinton for president and he’s running largely as a friendly outsider. When flooding devastated West Virginia earlier this summer, Justice opened up The Greenbrier resort, which he owns, to victims. Positive responses to natural disasters can be important for incumbent governors in their reelection bids: Justice isn’t an incumbent, but the glowing publicity for his action after the flood might be helping him.

Polling has consistently shown Justice leading, and even Republicans seem to concede that he’s ahead, just not by the double-digit margins some polls indicate. Meanwhile, some Republicans have been underwhelmed by Cole’s campaign, although they are hopeful that Trump will carry Cole over the finish line, and they have a lot of ammunition to use against Justice, including his history of late payments (or non-payment) of taxes.

While Republicans still have a very good chance to recover here, we’re forced to push this race from Leans Republican to Toss-up, and Justice probably is better than 50-50 to win. Nevertheless, recent history in that part of the country makes us cautious about overrating Justice’s edge. Looking back at the 2015 Kentucky gubernatorial race, state Attorney General Jack Conway (D) consistently led polls but only topped out at 45% in the last two months. In the end, he wound up losing 53%-44% to Matt Bevin (R). In the Mountain State, Justice could have enough appeal as a conservative Democrat to overcome the GOP’s edge at the top of the ticket — he’ll certainly have the resources — but if polls show him leading but significantly short of 50% as we get close to Election Day, that could be a warning sign. Another potential complication for Justice is the candidacy of Charlotte Pritt, who represents the Mountain Party, the Green Party’s West Virginia affiliate. Pritt is more well-known than most third-party nominees, having been the Democrats’ gubernatorial nominee back in 1996, when she lost to Cecil Underwood (R), as well as a notable general election write-in option in 1992 after coming up short in a primary challenge to incumbent Gov. Gaston Caperton (D). Liberal Democrats in West Virginia, what relatively few there are, might be turned off by Justice and could opt for Pritt instead. (There is a Libertarian candidate as well who may hurt Cole to some degree.)

Meanwhile, we now see Vermont as a Toss-up, instead of Leans Democratic. In a mirror opposite of West Virginia, we can see a Republican running far ahead of his party’s presidential candidate here. Lt. Gov. Phil Scott (R) is personally popular and is probably leading at the moment thanks to his proven electoral track record: He won by seven points in his initial election in 2010 and by large margins in 2012 and 2014. The Republican Governors Association has been running positive ads on his behalf, while Democrats believe they can attack Scott for being out of step with a liberal electorate on climate change and social issues. Like Justice in West Virginia, Scott is better-known than his opponent, former Transportation Secretary Sue Minter (D). But like Cole in West Virginia, Minter has the better party label for her state. If Minter ends up winning, she’ll be the first Democratic governor to directly succeed another Democrat in the history of the state.

Looming over this race is Bernie Sanders. Republicans are hoping that Democratic turnout in Vermont declines a little bit over bad blood from the primary, while Democrats are hopeful that Sanders will work to elect Minter. Sanders stayed out of the Democratic primary but some of his backers, including his campaign manager, endorsed a different candidate, former state Sen. Matt Dunne (D).

There seems to be a real possibility that Vermont will be one of Clinton’s best states but will elect a Republican governor, and that West Virginia will be one of Trump’s best states but will again elect a Democratic governor. Or maybe both will revert to their newfound and strong presidential party leanings.

Most of this year’s competitive gubernatorial races are open seats. Vermont and West Virginia do not feature an incumbent. Neither do Indiana, Missouri, and New Hampshire. North Carolina does feature an incumbent, but he’ll test the power of incumbency in gubernatorial races.

Incumbent governors, like most incumbents, are far more likely to win than lose. In presidential cycles in the post-World War II era, about four out of five gubernatorial incumbents have won reelection in November. But going back to 1992, 34 of 37 have won general election contests (92%) in presidential years. This would seem to augur well for Gov. Pat McCrory (R) of North Carolina, who is locked in a tight reelection battle with state Attorney General Roy Cooper (D). But as things stand, Cooper leads in both major polling averages by about four points. Not only that, but both aggregators find the Democrat running ahead of his presidential standard bearer by a couple of points. While the gubernatorial race is certainly close, because Cooper may be in a stronger position than Clinton suggests that a Democratic pickup could be on the cards in the Tar Heel State. McCrory has almost certainly been damaged by his decision to sign the controversial HB2 into law, which overturned anti-discrimination protections for LGBT rights, most notably a Charlotte ordinance addressing transgender access to public restrooms. Tellingly, Monmouth University’s recent survey pegged approval/disapproval for HB2 at a woeful 36%/55%. Of those who approve of the law, 74% say they’re backing McCrory, while Cooper gets the support of 72% of those who disapprove of HB2. Unusually for a challenger, Cooper has also outraised the incumbent McCrory, holding a $12.7 million to $8.7 million edge as of the end of the second quarter (June 30). In light of these developments in North Carolina, we’re shifting its rating from Toss-up to Leans Democratic.

Meanwhile, Indiana features a gubernatorial contest that once had an incumbent but now is an open-seat race. When Gov. Mike Pence (R) exited stage right to become Trump’s vice presidential nominee, it left the competitive Hoosier State tilt in flux. Multiple Republicans cast their hats into the ring to replace Pence on the ballot, but at the end of the day the state party central committee selected Lt. Gov. Eric Holcomb to become the GOP’s new gubernatorial standard bearer. Holcomb has taken a curious path to reach this point. A former adviser to popular ex-Gov. Mitch Daniels (R), Holcomb initially sought the Republican nomination for the state’s open 2016 Senate contest. But it soon became clear that he was unlikely to beat Reps. Todd Young or Marlin Stutzman for the Senate nod (Young went on to win). But another opportunity arose for Holcomb: In February, he exited the Senate race, and a month later he took over the lieutenant governorship following Lt. Gov. Sue Ellspermann’s (R) resignation. Then just about three-and-a-half months later, Holcomb was picked to replace Pence as the party’s gubernatorial nominee. Suffice to say, 2016 has been a wild ride for him.

But now Holcomb faces a tough fight with former state Speaker of the House John Gregg (D), who narrowly lost to Pence in 2012. The only public poll so far found the two in a neck-and-neck race. There’s a lot of uncertainty surrounding this race, even more than there was previously when it was a Pence-Gregg rematch. Gregg is already trying to tie Holcomb to the controversy surrounding aspects of Pence’s tenure in Indianapolis. Plus, Gregg starts with a name-identification and fundraising edge, in part because of complications regarding the transfer of money from Pence’s campaign account to Holcomb’s. But the new GOP nominee could conceivably benefit from his relative anonymity as a Republican at the top of the ticket in a red state that is likely to back Trump-Pence, and the Republican Governors Association is almost certain to use its vast resources to help Holcomb level the financial playing field. (Republicans are confident Holcomb will have all the money he needs.) It’s also worth considering that it may be hard for two down-ticket Democrats to win while Trump has the edge at the top, and as things stand the Senate race in Indiana is more likely to go Democratic than the gubernatorial contest. But all in all, the Gregg-Holcomb race seems uncertain and too close to favor one side at this point, so we’re moving it from Leans Republican to Toss-up.

There’s not a whole lot to say about New Hampshire right now because the primary still looms. Colin Van Ostern (D) and Chris Sununu (R), who serve together on the state’s Executive Council (which helps the governor manage the state), are both favored to win their primaries. But there could be a surprise in either race, particularly on the Republican side, where Manchester Mayor Ted Gatsas, state Rep. Frank Edelblut, and state Sen. Jeanie Forrester are all pushing Sununu in various ways. Assuming Sununu gets through the primary, he would probably start ahead given his last name (his brother and father have both been elected statewide). But Democrats are bullish on New Hampshire this year, and it’s possible that coattails from the presidential and Senate race could help the Democratic nominee. As of now this is a true Toss-up where much remains uncertain.

Both parties agree that Missouri, another open seat, is also a Toss-up, and some Republicans believe this is a better chance at a pickup than West Virginia, which on paper is a much more Republican state but is proving elusive for the reasons noted above.

State Attorney General Chris Koster (D) appears to be using the tried-and-true Democratic triangulation strategy from 10-15 years ago, running to the middle and courting typically conservative constituencies: For instance, the National Rifle Association just endorsed Koster. It reminds us of the way candidates like Ted Strickland (D) won Ohio’s governorship in 2006 or Mark Warner (D) won Virginia’s in 2001. That playbook has largely become obsolete for Democrats as the electorate has become more partisan and less persuadable, and the Democrats’ own electorate has gotten more liberal. Now-Sen. Warner almost found this out the hard way when he nearly lost in 2014 as Democratic turnout plummeted, and Strickland may be discovering it as well as he tries to attract Clinton voters in his own Senate race, which he is currently losing to Sen. Rob Portman (R). But Missouri is a more conservative state than Ohio and Virginia, so this game plan might work for Koster, who is a former Republican. For its part, the GOP plans to hit Koster over reports of pay to play in the attorney general’s office.

The Republican nominee, former Navy SEAL Eric Greitens, might have the right makeup for what feels like something of an outsider year in politics. Greitens is a political novice, and Democrats are hoping to exploit his lack of experience (“Where’s the beef?” they plan to ask, echoing the old Walter Mondale attack on Gary Hart in the 1984 Democratic primary). Both candidates should be exceedingly well-funded.

Finally, Gov. Steve Bullock (D) is trying to win a fourth-straight Democratic Party term in Montana’s governorship. Bullock took over from former two-term Gov. Brian Schweitzer (D). Bullock has faced ethical questions during his time in office for use of a state plane for political purposes, but he appears to retain a good deal of personal popularity and should be able to run significantly ahead of Hillary Clinton. Republicans are hoping that wealthy businessman Greg Gianforte (R) puts more of his money into the race and closes the gap. We’ve had this race at Leans Democratic all cycle, and unless we get convincing evidence one way or the other, that’s probably where it’s going to stay. Bullock is the incumbent, and the statistics about the power of incumbency apply to him, too.

While many of the gubernatorial races this year appear competitive, some of them seem fairly easy to call. Republicans look very solid in North Dakota, an open seat, and Utah, where Gov. Gary Herbert (R) is running for a second full term. Meanwhile, Democrats appear to be fine in Delaware, an open seat, and also in Oregon and Washington, solidly Democratic states where Republicans sometimes come very close to winning the governorship but haven’t elected GOP governors since 1980 (Washington) or 1982 (Oregon). Some polls have shown Gov. Kate Brown (D) only leading oncologist Bud Pierce (R) by single digits as she seeks election to the seat she inherited after the resignation of former Gov. John Kitzhaber (D). She might have a harder time in 2018 if and when she seeks election to a full term, but she appears OK for now. We’re leaving that race at Safe Democratic, and we’re also moving Washington to Safe Democratic from Likely Democratic. Gov. Jay Inslee (D) won the all-party primary by double digits over former Seattle Port Commissioner Bill Bryant (R), and there’s just not much reason to think Bryant will roar back by the time of the November election.

These five states probably will go along with their presidential results this cycle. In the other seven states, there’s much more question about that, which means we could be in store for some odd, very close results in this year’s gubernatorial races.

We realize that we have a lot of Toss-ups right now: the rating now applies to five of the 12 races (Indiana, Missouri, New Hampshire, Vermont, and West Virginia). But our sources right now are all over the map on these races, and there is still a lot of uncertainty. As is our tradition, we’ll offer picks in all these races by Election Day. Overall, Republicans hold a 31-18 edge in governorships (there is one independent, Alaska’s Bill Walker). Our current ratings show the Democrats picking up a seat (in North Carolina), but four of the five Toss-ups are currently held by Democrats. So Republicans still have a decent chance to add a net seat or two to their already impressive collection of state governorships, although if Democrats have a good night they might hold the line. Then both parties will look ahead to the twin, open seat Mid-Atlantic prizes being contested next November — New Jersey and Virginia — and then 2018, when the lion’s share of state governorships are contested.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

Geoffrey Skelley is the Associate Editor at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

Larry J. Sabato is the director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik

See Other Political Commentary by Geoffrey Skelley

See Other Political Commentary by Larry Sabato

See Other Political Commentary

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.