The State-Level Differences Between the Presidential and Senate Races

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Split outcomes between presidential and Senate results saw a resurgence in 2024, as at least four Donald Trump-won states sent Democrats to the Senate.

— Republicans still took the majority in the Senate because while Sens. Jon Tester (D-MT) and Sherrod Brown (D-OH) performed notably better than Kamala Harris, they did not do so by enough to hold their seats.

— Across most key Senate races, Senate Democrats ran better than Harris in rural parts of their states but were comparatively weak in some suburban counties.

— In one of Harris’s best states, Maryland, former Gov. Larry Hogan (R-MD) stood out as Republicans’ top overperformer, although Harris’s 26-point margin in the state was too much for him to overcome.

How the Senate contests stacked up to the presidential race

Going into last week’s elections, the presidential contest and the race for the House both seemed like true Toss-ups. But Republicans had been clear favorites to capture the Senate for months in advance. Last week, Republicans indeed took Congress’ upper chamber, although the likely size of their majority—53 seats—is not completely set.

Donald Trump carried West Virginia, already one of his best states in his past races, by more than 40 points, and Gov. Jim Justice (R) won the seat of retiring Sen. Joe Manchin, an independent who caucuses with Democrats, by a comparable margin. Though this was a flip that surprised absolutely no one, it did have some historical significance: the next Congress will mark the first since the 1950s that West Virginia will be represented by two Republicans in the Senate.

After West Virginia, Montana represented Senate Republicans’ best target. To us, it seemed clear that Sen. Jon Tester (D) had fallen behind businessman and veteran Tim Sheehy (R) by Labor Day, prompting us to move the race to Leans Republican in early September. Though Tester ended up running about 13 points ahead of Kamala Harris, his 52%-45% loss to Sheehy was a result that basically confirmed what polling had suggested. As with the flip in West Virginia, Tester’s loss was a “sign of the times”: next year, Sheehy, along with outgoing National Republican Senatorial Committee Chairman Steve Daines, will become Montana’s first all-Republican Senate delegation in the popular vote era, going back more than a century.

Our September move in Montana left Ohio as our sole Toss-up contest in the Senate—that was the case for virtually the entire post-Labor Day stretch of the campaign, although we moved it into the Leans Republican column for our final update. Our thinking was that while Sen. Sherrod Brown (D) seemed to be holding his own in polling, Trump’s coattails in the state would likely help car dealer Bernie Moreno, the GOP nominee, get the job done. In both his previous races, Trump carried Ohio by 8 points—as that margin expanded to more than 11 points, Moreno beat Brown 50%-46%.

While we favored Republicans in all three of those seats, one of the bigger questions for us going into Election Night was if Republicans could flip any of the Senate seats that we rated as Leans Democratic. That list included Arizona and Nevada in the West, and the trio of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin in the Industrial North. With that in mind, we wrote the following in one of our Senate updates from mid-October:

“Five of our seven presidential Toss-up states have Senate races this year, and we put all of them in the Leans Democratic category, although, as mentioned above, that designation is somewhat tenuous in several cases. But we can see those Democratic incumbents—or, in the case of Arizona and Michigan, well-funded nominees—outpacing Harris by just enough to hold on if Trump very narrowly carries their states.”

Our hypothesis, to say the very least, was put to the test.

Trump carried all seven of the key presidential battlegrounds. But down the ballot, Democrats appear to have prevailed in at least four of the five presidential Toss-ups states that hosted Senate races. By the day after Election Day, it was apparent that Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) had secured a third term and that Rep. Elissa Slotkin (D, MI-7) had held Michigan’s open seat for Democrats. In Nevada and Arizona, states that take longer to count their votes, Sen. Jacky Rosen (D-NV) and Rep. Ruben Gallego (D, AZ-3) subsequently won their respective races.

That leaves Pennsylvania.

Without getting too deep into the weeds of ballot processing, as of this writing, former Bush Administration official and 2022 GOP Senate candidate David McCormick leads three-term Democratic incumbent Bob Casey by more than 26,000 votes in a race where nearly 7 million were cast. Last week, the Associated Press called the race and McCormick declared victory—he argued that Casey has no path to retaking the lead—although the Casey campaign has emphasized that ballots are still being counted. The race appears headed to a recount. Obviously one would much rather be McCormick than Casey at this point even as several news organizations have held off on calling the race.

But even if Democrats lose Casey, they will still hold several seats in Trump-won states thanks, at least in part, to ticket-splitting.

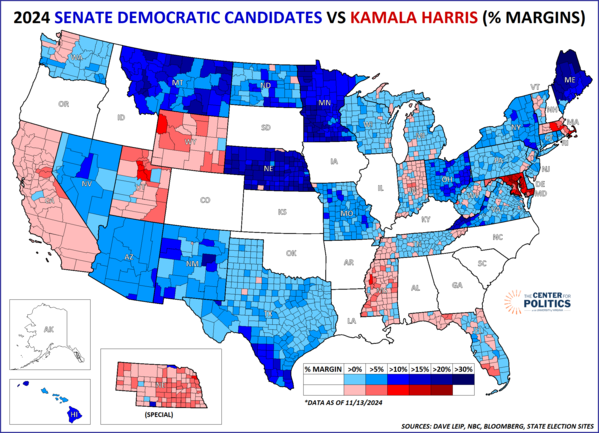

So with that, we’re taking a crack at making sense of ticket-splitting at a macro level between the presidential and Senate races. Map 1 compares the margins that Senate Democratic candidates got to those of Harris. In blue counties, Senate Democrats performed better than Harris, while the reverse is true in red counties. What follows the map are some of our general observations. Let’s also keep in mind that the differences between the presidential and Senate races aren’t just about voters actually splitting their tickets—it also seems clear that some voters (likely disproportionately Trump voters) skipped down-ballot races. We plan to take a closer look at this soon. For now, though, let’s look at the differences in margin between the presidential and Senate races across the country.

Map 1: Senate Democratic candidates vs Kamala Harris by county

Notes: Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Angus King (I-ME) are considered Democrats for the purposes of Table 1, as is Nebraska independent candidate Dan Osborn. The map considers their margins compared to their Republican opponents; several western states, especially California, are still tabulating ballots.

— Out of the races that the Crystal Ball rated as competitive (those that were not in the Likely or Safe category for either side), Tester posted one of the larger overperformances, running 13 percentage points better than Harris in Montana. Considering that, it’s not surprising that Tester outpaced Harris in every county. But one consistent pattern was that Tester held up especially well in counties that have large Native American populations. In fact, four of Tester’s five best overperformances came in counties that include reservations: Big Horn (Crow Reservation), Blaine (Fort Belknap), Roosevelt (Fort Peck), and Glacier (Blackfeet Nation). Some of those counties swung more than 10 percentages points to Trump as the presidential level, so Tester could have also benefitted from some down-ballot lag. While support with that bloc has been a key part of Tester’s past overperformances, he may have been helped this time from an audio recording that surfaced of Sheehy seeming to deride Native Americans.

— In Ohio, Brown ran 7.6 percentage points better than Harris, suggesting that he’d have been able to hold on if she could have improved on Biden’s 2020 8-point margin instead of falling behind it. In what would become a theme of other contested, Democratic-held seats, Brown held up best in traditionally Democratic rural parts of the state that have zoomed towards the Republicans in recent years, but he ran closest to Harris in counties that have only trended Democratic more recently. In Brown’s case, many of the counties where he ran double-digits better than Harris were in the eastern part of the state. Meanwhile, the only two counties that gave him less than 5-point overperformances were Hamilton (Cincinnati) and Delaware (Columbus’s northern suburbs). Given the state’s internal shifts, we viewed Delaware County as, probably, a must-win for Brown. Though he lost it by less than 2 points, it was perhaps significant that it ended up left of the state—when Brown first entered the Senate, in 2006, he won by 12 points but lost Delaware County by 16 points.

— In the competitive trio of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, Democratic Senate candidates broadly, if only slightly, outperformed Harris in most counties in their states. That said, there were some historically Republican counties that showed a degree of down-ballot lag: the “WOW” counties around Milwaukee and parts of western Michigan stand out, as do some of the Philadelphia “collar” counties. Given the exceptionally close margin of the race, Casey’s lag in the collar counties could have been enough to be determinative. In late October, McCormick campaigned with former U. N. Ambassador Nikki Haley in the Philadelphia suburbs; the three red Pennsylvania counties on Map 1 were also her top three counties against Trump in the state’s spring presidential primary.

In the case of Wisconsin, we wonder if Baldwin’s endorsement from the state’s chapter of the Farm Bureau, a group that rarely endorses Democrats, had an outsized impact by reinforcing her credibility in rural counties—the handful of counties where she performed 5 points better than Harris were all in the western or northern parts of the state.

Slotkin would have carried her Lansing-area MI-7 by a few points even as it flipped to Trump at the presidential and House levels. Oakland County, a large county north of Detroit’s Wayne, also stands out to us. Given its profile, we would have expected it to be one of those places that would be more comfortable with Republicans down the ballot, but Slotkin still ran a few points better than Harris there.

— Out west, and though there are still some votes to be counted, it seems Rosen and Gallego outran Harris by more than the Industrial North Democrats did. While it was one of the counties she was relatively close to Harris in, Rosen performed nearly 5 points better than Harris in Las Vegas’s Clark County. In Arizona, Phoenix’s swingy Maricopa actually represented one of Gallego’s best performances: he ran nearly 9 points better than the top of the ticket. Exit polling, and pre-election polls, suggested that one of the drivers of Gallego’s relative strength was his better standing with the Hispanic community. Santa Cruz County, a border county that we flagged a few weeks ago, seems to back this up: in this heavily Hispanic county, Gallego fared 11 points better than Harris. Gallego’s best county, compared to Harris, though, was actually Greenlee, a former mining county in the eastern part of the state that can be called the state’s most ancestrally Democratic area.

— In Texas, Sen. Ted Cruz (R) ran just over 5 points under Trump but still defeated Rep. Colin Allred (D, TX-32) by a comfortable 9 points. Aside from South Texas, where there was some visible pro-Democratic down ballot lag, Allred ran just enough ahead of Harris in metropolitan Texas to hold some large counties that Trump flipped at the presidential level, notably Tarrant (Fort Worth) and Williamson (north of Austin).

— For the purposes of this map, we considered independent Nebraska candidate Dan Osborn to be a Democrat. Because of that, he was technically the biggest Democratic overperformer, running nearly 14 points ahead of Harris. Though Osborn tracked relatively close to Harris in Omaha’s Douglas County, the heart of the state’s 2nd District, according to our calculations, he carried the Lincoln-based 1st District, which moved from Trump +11 in 2020 to Trump +13 this year. Another independent who had strong crossover support was Sen. Angus King (I-ME), whose support in northern Maine stands out.

— It would be hard to talk about Democratic overperformers without mentioning Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN). Though this was the first time in her career where she did not carry all eight of the state’s congressional districts, she ran about a dozen points better than the top of the ticket, and did so by at least a few points in every county. Klobuchar’s best counties, compared to Harris, tended to be located in the 7th District, which makes up much of the western part of the state: her 18-point deficit there was half of Harris’s 36-point loss in the district.

— Finally, in our state, Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA) did about 3 points better than Harris, winning by 8.6% while Harris carried Virginia by 5.6%. For Kaine, it was not an unfamiliar situation: when he first won his seat, in 2012, he ran about 2 points better than Barack Obama in the state. Aside from southwestern Virginia, where he was especially strong compared to the presidential results in both cases, Kaine’s strength across the state was a little more uniform this time—in 2012, Southside stood out as an area where Obama slightly but consistently outpaced him.

While we’ve focused so far mostly on Democrats overperforming the top of the ticket, some Republican Senate candidates across the country turned in strong showings of their own, although many came in states that we did not rate as competitive.

— As expected, the strongest Republican nominee, compared to Trump, was former Gov. Larry Hogan (R-MD). As of this writing, Trump’s deficit in Maryland stood at about 26 points, while Hogan got within 10 points of Prince George’s County Executive Angela Alsobrooks (D). Hogan’s strongest counties tended to straddle the state’s two main metro areas: he ran more than 20 points ahead of Trump in Anne Arundel, Howard, and Carroll counties.

— In New England, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), and to a much lesser extent, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), were Democratic senators who underperformed Harris in an area where their colleagues did better. Their performances might have something to do with the fact that, of the five senators who were up this year from what can be a parochial region, Sanders and Warren are seen as the most “national” figures.

— In Florida, Sen. Rick Scott (R) finally won a statewide race by a solid margin, although he very slightly underran Trump (winning by 12.8% instead of 13.1%). In 2018, Scott’s overperformance in the Orlando area—a place that has a sizable Puerto Rican population—was key to his narrow win over then-Sen. Bill Nelson (D). The Orlando metro area was again a strong area for Scott; we’d have to do more precinct-level digging to say that it was for the same reason, but Puerto Ricans may not have shifted to Trump as heavily as other Hispanic groups did, so Scott may have had some room to improve on Trump there. Elsewhere in Florida, the red in the panhandle aligned with the path of Hurricane Helene—voters may have rewarded Scott for taking a visible role in managing the storm’s aftermath. Despite garnering public support from some big names in MAGA circles, Scott lost a bid for the Majority Leader position to Sen. John Thune (R-SD) on Wednesday.

— Early on Election Night, we looked to Hamilton County, Indiana as something of an early bellwether. We expected this fast-growing suburban county north of Indianapolis to shift towards Harris, perhaps markedly so. While Harris improved there, it was not by much: she cut Biden’s 7-point loss there to just 6 points. Down the ballot, Rep. Jim Banks (R, IN-3), even as a very Trump-aligned candidate himself, got a notable boost in that area, as he won Hamilton County by 12 points. Banks, as the map may suggest, represents the Fort Wayne area in the House, which makes up the northeastern corner of the state.

— In Mississippi, Sen. Roger Wicker’s (R) strength in the heavily Black delta region of the state reminded us of his late colleague, the long-serving Thad Cochran (R). Cochran, an appropriator with a gentlemanly demeanor, was known for his crossover appeal with Black voters. With fellow Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith (R) being seen as the more “MAGA”-aligned of Mississippi’s senators, it seems like Wicker may be picking up the Cochran mantle.

— In Wyoming, Trump’s best state for the third time, Sen. John Barrasso (R), who won a fourth term and will take over as Majority Whip in the next Congress, won by an even bigger margin. Barrasso was especially strong in Teton County, which includes several prominent skiing locations and national parks. It is easy to see some more affluent voters in this touristy area balking at Trump while backing Republicans for lower offices.

— Finally, in what could probably be called the most Trump-skeptical red state, Utah, Rep. John Curtis (R, UT-3) will replace retiring Sen. Mitt Romney (R) next year. It appears that Trump is on track to about match his 2020 margin in Utah—just over 20 points—while Curtis is matching Romney’s 30-point margin from 2018. Curtis, who was mayor of Provo before entering Congress, had obvious strength along the Wasatch Front, a stretch of counties in northern Utah that account for most of the state’s population. Curtis won the counties that make up the Wasatch Front 59%-35% while Trump did so by 55%-42%.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.