Less Than A Year Out: A Redistricting Update

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman

Going over new maps in NC, TX, and other states.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— With some more populous states passing new district maps, the 2022 congressional landscape is getting a bit clearer.

— In Texas and North Carolina, Republicans took contrasting approaches — they were relatively tame in the former and more aggressive in the latter — but should likely net seats out of both states.

— In smaller states, like Alabama and West Virginia, redistricting has basically panned out as we expected.

The national redistricting picture takes shape

Though the Crystal Ball’s attention over the last few weeks was mainly on the hotly-contested gubernatorial race in our home state, we have also been keeping tabs on the redistricting situation around the country. With Virginia’s contest settled, we thought we’d take a look at states that have enacted new plans.

It may be hard to believe, but there is now less than a year to go until the 2022 midterms (Election Day next year is Nov. 8). Still, only about a dozen states have completed the redistricting process — and in some cases (like Alabama and North Carolina), there is at least some chance litigation may further alter the shapes of the newly enacted districts. While we already covered some states that passed new plans (Colorado, for instance), we’ll take a trip across the country to see how redistricting has played out in a handful of states.

One note: While Illinois’s Democratic-controlled legislature has passed a gerrymander designed to elect a 14-3 Democratic delegation, Gov. J.B. Pritzker (D-IL) had not yet signed it into law as of this writing. So we’ll hold off on a deeper analysis until he does. Idaho and Montana, two Republican states that employ non-partisan commissions, are also in the final stages of their redistricting process — we’ll likely have more to say on those states soon.

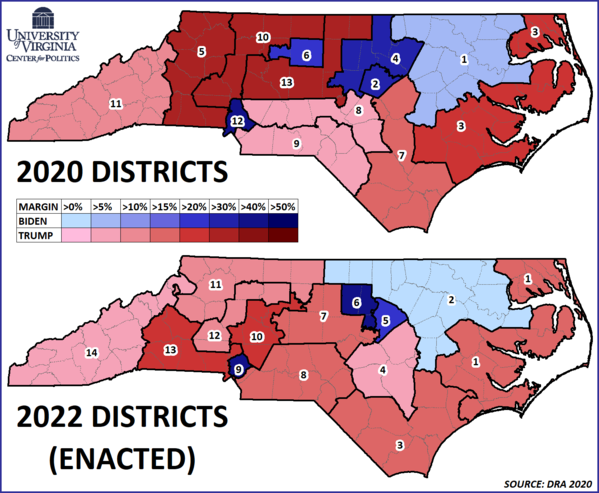

Before we go state by state, Table 1 shows our updated House ratings for the states that have completed redistricting so far. We will keep adding to the list as more states complete maps.

Table 1: Crystal Ball House ratings

Alabama

Last week, Gov. Kay Ivey (R-AL) signed off on a new congressional plan that the state’s Republican legislature passed. With only 6 county splits between 7 districts, the new map is essentially a cleaner version of the existing plan. Districts 5 and 6, which make up the Huntsville and Birmingham areas, respectively, contract while the Black-majority AL-7’s tendrils into Birmingham and Montgomery are smoothed out.

Alabama has not seen a truly competitive House race for over a decade now, and with this map, we expect that trend could continue for another 10 years.

Though lawsuits have already been filed against the plan, which charge that Black voters are too concentrated in AL-7 — a second Black-majority seat can easily be drawn — the Crystal Ball is assuming the enacted map stands. Districts 1 through 6 will stay Safe Republican, while District 7 is Safe Democratic.

Arkansas

The 2020 cycle was the first time, at least post-Reconstruction, where Republicans controlled the redistricting process in Arkansas. Going into the process, it seemed Republicans didn’t have much reason to make major alterations to the existing map, as they already held all 4 seats. Importantly, the GOP’s grasp on their districts seemed relatively firm. Their sole incumbent who could have used some shoring up was Rep. French Hill (R, AR-2), who represents the Little Rock area. Though Hill found himself on Democratic target lists in recent cycles, he won by a clear 52%-46% in 2018, and an even larger 55%-45% in 2020 — solid margins, but not landslides.

As it turned out, Republicans’ solution was to split Pulaski County (Little Rock) 3 ways. While the lion’s share of the county remains in AR-2, several of Little Rock’s Black-majority precincts were transferred into the adjacent 1st and 4th districts — these are both vast rural districts that have little in common with the state’s capital city. To make up for losing precincts in Pulaski County, AR-2 gained all of Cleburne County, which gave Trump over 80% of the vote in 2020. With that trade, AR-2 shifted a few points rightward: Trump would have carried the new district 55%-42% last year, up from the 53%-44% spread on the current plan.

Gov. Asa Hutchinson (R-AR) registered some discontent with the Little Rock split, noting some features of the map “raise concerns.” Still, Hutchinson, showed some deference to Republican lawmakers and let the plan become law without his signature (in Arkansas, bills that pass the legislature become law if the governor simply declines to take action, as opposed to signing or vetoing the legislation).

With the new map, the Crystal Ball rates all four districts as Safe Republican. The changes in AR-2 should insulate Hill for at least a few more cycles and, while AR-3 may be in on the board by the end of the decade, Republicans should have no problems clearing 60% of the vote there. The two rural districts, AR-1 and AR-4, are blood red.

Iowa

Since the 1980 round of redistricting, Iowa’s congressional districts have been drawn by staffers of its nonpartisan Legislative Services Agency. Though the legislature is not obligated to accept the LSA’s recommendations, lawmakers have nonetheless signed off on its plans. Still, with Republicans in full control of state government for the first time in decades, it seemed that the tradition of deference to the LSA would be put to the test — under Iowa law, if legislators rejected 2 LSA plans, they’d be free to draft their own proposals.

For a time, it seemed like the legislature would indeed end up snubbing the LSA. In mid-September, the LSA’s initial redistricting plan reconfigured the current map, that features 4 Trump-won seats, to the benefit of Democrats: it turned Rep. Cindy Axne’s (D, IA-3) Des Moines area seat into a narrow Biden district (Trump barely won the current version), while creating a new blue-leaning seat in eastern Iowa. Legislators voted down the plan, although they seemed to complain most, at least in public, that the state legislative maps double-bunked too many incumbents.

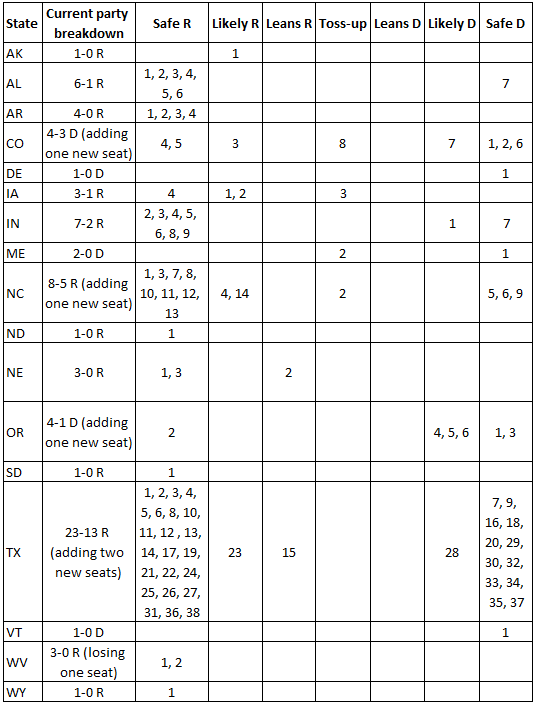

A few weeks later, the LSA released its second draft. This time, the status quo was essentially preserved: while IA-4, anchored in the rural northwestern part of the state, was kept as a deeply GOP-leaning seat, the other 3 districts would have favored Trump by lesser margins. The second plan passed the legislature and was signed into law by Gov. Kim Reynolds (R-IA).

Though the newly enacted plan is basically similar to last decade’s plan, there are some differences. First, at a purely cosmetic standpoint, the numbering of the two eastern districts is swapped. The new IA-1 includes Iowa’s portion of the Quad Cities, while IA-2 is situated in the northeastern corner of the state — though the last two decades marked a departure from this, the new map marks something of a return to the map that was in place until the 2000 census.

At a more logistical level, though first-term Republican Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks’ home county, Wapello, was moved into Axne’s IA-3, she’ll be running for reelection in the new IA-1. Geographically, IA-1 has more in common with her current IA-2 — and it is slightly more Republican than IA-3. Miller-Meeks’ move is not without precedent: since the LSA doesn’t take incumbent residences into consideration, some members have had to similarly adjust in previous cycles.

We’d rate IA-1 as Likely Republican and IA-3 as a Toss-up. While Democrats seem to be excited about their candidate in IA-2, state Sen. Liz Mathis, we’d rate Rep. Ashley Hinson (R, IA-1) as a favorite, and would call that contest Likely Republican. Finally, in IA-4, there is little question that Rep. Randy Feenstra (R, IA-4) will secure a second term.

Though Republicans could well sweep the delegation on this functionally minimal-change map, this plan also leaves them room to fall. In a blue, or even neutral, cycle and if Democrats are competitive statewide, they could limit Republicans to just IA-4. This was the case in 2018: the Democratic nominee for governor, Fred Hubbell, took 47.5% statewide but carried 3 districts. The congressional split mirrored that breakdown, and the new plan retains 3 Hubbell-won districts.

Map 1: Iowa 2020 president and 2018 governor by 2022 districts

North Carolina

North Carolina, which gained a seat this decade, is a state known for bitter partisan battles — the recent remap was no exception, as Democrats objected to a Republican-drawn map aimed to expand their majority in the state’s congressional delegation. As Gov. Roy Cooper (D-NC) does not have veto power over redistricting-related bills, the Republican-controlled legislature engineered a plan where their candidates would be favored in 10 of 14 districts. A decade ago, when the state was keeping 13 seats, Republicans passed a similar plan with 10 red seats. Two mid-decade redistrictings later, the GOP was forced to cough up two additional seats to Democrats because of an intervention by Democrat-led state courts — in 2020, the congressional delegation stood at 8-5 Republican.

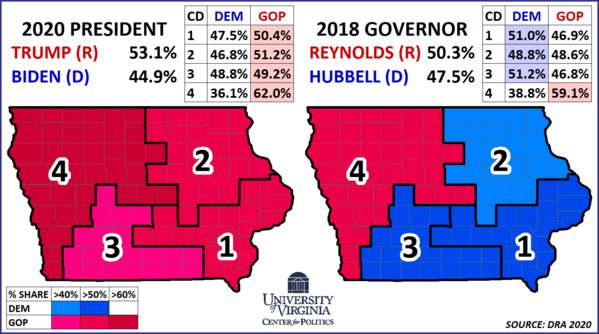

Before even getting into the partisanship of the districts themselves, something that stands out about the new North Carolina map is its wholesale renumbering. Starting out east, District 1 takes up much of the Atlantic coast, while, nestled in Appalachia, District 14 is coterminous with the western edge of the state — for the past 3 decades, these districts were labeled NC-3 and NC-11, respectively. Map 2 compares the current and newly-enacted districts:

Map 2: North Carolina districts, 2020 vs 2022

While this new numbering is probably more logical, those of us who have been following the state’s politics will almost surely need some time to adjust. As an aside, this seems to be somewhat of a theme this cycle: in West Virginia, which lost a seat, the legislature passed a plan that designated its northern seat as WV-2 (it had been WV-1 for many decades), while the Arizona commission seems poised to pass a plan that shakes up the states’ district nomenclature for the third consecutive cycle.

As with the map Republicans drew in 2011, Democrats have three ironclad seats. The new NC-5 is essentially the successor to the current NC-2 — it is a Raleigh-area seat confined to Wake County and is safe for first-term Rep. Deborah Ross (D, NC-2).

Next door, NC-6 is the successor to the current NC-4; it takes in part of western Wake County, but is mostly based in the two university counties of Durham and Orange (Duke and UNC, respectively). Rep. David Price, the dean of the state’s delegation, is retiring for 2022 — he has represented the district for all but 2 years since 1986 — and whichever Democrat emerges from the primary is essentially assured victory in this 73% Biden seat.

The last securely blue seat is NC-9, which overlaps with the current NC-12. Rep. Alma Adams (D, NC-12) had to relocate from Greensboro to Charlotte to keep her seat under the state’s 2016 remap, but seems entrenched in the area.

The sole district that seems likely to see a truly competitive race next year is NC-2, which replaces the current NC-1. This district was drawn to be majority-Black for 2012, but was unpacked for 2020 — its Black share dropped to 44%, and the current plan takes that down to 41%. Rep G. K. Butterfield (D, NC-1), who has represented the seat since 2004, is well-known in the area, but should see a more competitive race in a district where the Black share is reduced.

From 2012 to 2018, Butterfield had most of Durham in his district, which helped to provide him easy majorities in those cycles. But Durham was removed from the seat in 2020, and Butterfield was held to a single-digit margin that year. Under the remap, his district loses some blue precincts in Pitt County (Greenville) and becomes less Democratic. Northeastern North Carolina, though it has a sizable Black population, is still a mostly rural area, and has drifted redder since President Obama left office. In 2014, the late Sen. Kay Hagan (D-NC), lost reelection by just under 2 percentage points statewide but would have carried the new NC-2 by almost 10 points. Last year, as Biden lost North Carolina by 1.3%, the district backed him by just 2.4%.

Normally, given Butterfield’s history in the district, we’d start this race off as Leans Democratic, but we think Toss-up is more appropriate for now, given the national environment. There is also a chance this district gets altered before the election, as the drop in its Black share could fuel legal challenges — considering North Carolina was the only state to go through 3 congressional maps last decade, this would not be out of the ordinary. But for now, we’re assuming these lines hold.

Though Butterfield’s situation under the new map is less than optimal, first-term Rep. Kathy Manning (D, NC-6) is clearly the most imperiled Democrat. For 2020, with prodding from state courts, Republicans drew a compact Greensboro-area seat — containing all of Guilford County (Greensboro), and most of Forsyth County (Winston-Salem), the seat easily elected Manning. But that district is now split between 4 districts that would have all given Trump over 55% of the vote in 2020. Assuming the plan stands, Manning would not have any good options.

Of the 10 Trump-won seats on the new map, 2 are potential Democratic targets. Just south of the Raleigh area, the new NC-4 is an open seat that contains all of Fayetteville. Although the district’s other counties are more Republican — Johnston County, in particular, is one of those large, but still-red, exurban counties that has helped to keep North Carolina’s electoral votes in the GOP column — Gov. Cooper lost it by just 685 votes last year, and Biden took 46% there. Perhaps NC-4 could flip in a cycle where the national environment is good enough for Democrats.

In western North Carolina, controversial first-term Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R, NC-11) was given a more competitive, but still GOP-leaning seat. His Asheville-area seat reaches up the Blue Ridge to grab most of Watauga County, a Romney-to-Clinton county which houses the college town of Boone (Appalachian State University). Conveniently for Rep. Virginia Foxx (R, NC-5), who currently represents that area, all of Watauga County except the precinct that she lives in was transferred to NC-14. In any case, Trump’s 2020 margin in NC-14 is 7.4 points, down from 12 points under his current seat. So the district likely won’t be an immediate Democratic pickup opportunity, but it is a seat that Republicans won’t want to take for granted.

Finally, a word on some of the Safe Republican seats. As the Crystal Ball alluded to in our North Carolina redistricting preview, the new district (labeled NC-13 on the map) seems drawn for state House Speaker Tim Moore (R) — although there was a report last night that Cawthorn is switching to this district, which would likely set up a contested primary. In the Greensboro area, former Rep. Mark Walker (R, NC-6), who is currently struggling to gain traction in his bid for Senate, could switch gears and mount a House comeback bid. Though his home would be drawn into Foxx’s district, the new NC-7 is an open seat that contains areas he represented while in office.

Texas

In 2018, Texas seemed to emerge as a true congressional battleground state: Democrats netted 2 seats out of the Lone Star state, cutting Republicans’ advantage in the state’s delegation from 25-11 to 23-13. Importantly, several of the 23 winning Republicans that year were held to just single-digit margins of victory. Though Texas Democrats had high hopes going into 2020, there was no change in the delegation’s composition, as Republicans held all their seats — some of which featured competitive open seat races.

Still, if the current Texas map had to remain in place for another few cycles, several GOP-held seats could be liable to flip. Republicans seemed to draw their new map with this in mind: as they already have a comfortable majority of the congressional delegation, they were largely on the defensive.

After the 2020 census, Texas gained 2 seats. That was not as many as the 4-seat windfall it saw after the 2010 census, but Texas was the only state this cycle to gain more than a single new district. While Republicans could have found ways to ensure both the new seats were GOP-leaning, they shrewdly added a new Democratic seat in the Austin area.

The inaugural iteration of TX-37 is confined almost entirely to Travis County (Austin) and would have given Biden a better-than 3-to-1 vote last year. Veteran Rep. Lloyd Doggett (D, TX-35) currently holds a serpentine district which includes parts of Austin but it is, by composition, more oriented towards San Antonio. Though he came to represent TX-35 because it was the least-bad option that a hostile GOP legislature gave him a decade ago, the district is an odd fit for Doggett — he has built a career on his rapport with the state’s liberal capital city. So with his Austin roots, it wasn’t too surprising when he announced he’d move over to the new TX-37.

Despite Doggett’s longevity, he may not have the primary field to himself. Julie Oliver, who Democrats nominated to run in the red-leaning TX-25 in 2018 and 2020, remains popular with local progressives — she could be a feasible primary challenger. In a twist of irony, the 1974 edition of the Almanac of American Politics identified Doggett, then an upstart 26-year-old state senator, as a potential primary challenger to longtime Rep. J. J. Pickle, an LBJ ally — though Doggett didn’t run against Pickle, the primary in this Austin-area seat may still be worth watching decades later.

Meanwhile, the new 38th seat was added as a GOP-leaning seat in the Houston area. Wesley Hunt, Republicans’ 2020 nominee against Democratic Rep. Lizzie Fletcher in the adjacent TX-7, is running with the support of House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R, CA-23) and is a strong bet to be TX-38’s first representative.

Though Hunt gave Fletcher a close call in 2020 (she won by 3 points), future general elections shouldn’t be too much of an issue for her — assuming she can make it past the primary. As her suburban Houston TX-7 moves westward into Fort Bend County, it shifts from a heavily white, electorally marginal seat to a deep blue majority non-white district. North of Houston, Rep. Colin Allred (D, TX-32) is also a second-term Democrat who gets “vote sinked.” His TX-32 was a Romney-to-Clinton district that was redrawn to have given Biden 66% in 2020.

In a bad Democratic environment in 2022, Allred and Fletcher likely both would have been vulnerable had their current seats not changed. However, even if Republicans had beaten them in 2022, they would have had a hard time holding onto their seats long term, and by making both safe, Republicans have improved their position elsewhere.

First-term Rep. Beth Van Duyne’s (R, TX-24) district, for example, moved eastward to take in the University Park area in Dallas — this is one of the redder neighborhood’s in Allred’s current TX-32. Van Duyne, impressively, won her district last year (it was an open seat) as Biden carried it with 52% — that share drops to 43% in the new district. Similarly, the creation of the new TX-37 in Austin helps take pressure off of Reps. Michael McCaul (R, TX-10) and Chip Roy (R, TX-21), both of whom drop some deep blue precincts in the capital region.

Republicans also helped their vulnerable members by unpacking some dark red seats. In east Texas, TX-4 has long been a rural district that has hugged the Red River — the late House Speaker Sam Rayburn’s home county, Fannin, was emblematic of the area. But as the Dallas metro area has expanded, TX-4 has taken on a more exurban character. Though it retains a handful of rural counties, the district reaches down into Collin County to grab 320,000 people who, collectively, lean Democratic. Most of those new residents were formerly in Republican Rep. Van Taylor’s TX-3, which was essentially coterminous with Collin County last decade. While shedding those Democratic-voting residents, TX-3 retains a Collin County focus but reaches west to take exurban Van Zandt County, which is currently in TX-4 — that switch bumps Trump’s share in TX-3 from 50% up to 57%.

Though Texas Republicans seemed to be going for a largely defensive plan, one of the biggest stories out of the 2020 election was the party’s gains in heavily Hispanic South Texas. So given some of last year’s trends, District 15 — and to a lesser extent, District 28 — seemed like an inviting target. TX-15, one of the “Fajita Strip” districts that starts in the Rio Grande Valley and runs north to San Antonio, has been in Democratic hands since it was first established, after the 1900 census. But last year, Rep. Vicente Gonzalez (D, TX-15) won a third term by just under 3 points — and Biden’s margin in the district was even slimmer.

As redistricting turned TX-15 into a Trump district, Gonzalez is seeking reelection in the next-door TX-34, which is still solidly Democratic — we rate the open seat contest in District 15 as Leans Republican. Republicans had something of a setback in TX-15 when their frontrunner, 2020 nominee Monica De La Cruz, was recently accused of child abuse, as part of what appears to be a nasty divorce battle, although the area’s pro-GOP trend could help the national party recruit other candidates if this story proves damaging to De La Cruz (the report just emerged, and it’s sometimes hard to know what is true and what is not in a heated divorce).

Rep. Henry Cuellar (D, TX-28) keeps his base in Laredo, but is given a seat that Biden only carried by 7 points. A Blue Dog, Cuellar usually runs ahead of the top of the ticket, but if he is primaried by a more liberal Democrat — he was barely renominated in 2020 against progressive Jessica Cisneros, who is seeking a rematch this cycle — TX-28 could be within reach for Republicans. For now, we’ll call the district Likely Democratic.

North of TX-28 is TX-23, which Rep. Tony Gonzales (R, TX-23) held in something of an upset last year. A Clinton-to-Trump district, TX-23 was one of the prime swing districts of the last decade, but it moved a few points rightward in redistricting. Still, this is probably the only Republican-held seat that Democrats could put into play, at least in the short term. We’re starting it off as Likely Republican.

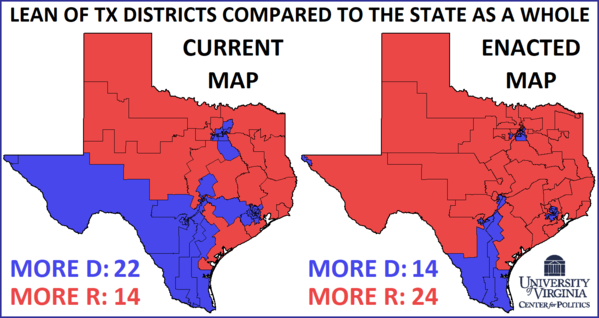

Not surprisingly, the product of all these changes is that Republican districts are more firmly red. One way to see this is by looking at how the individual districts compare to the state. In 2020, 22 of Texas’s 36 districts were more Democratic than the state as a whole. In other words, even though Biden lost some Republican-held districts, he performed better in them than he did statewide. He lost the current TX-23, for example, by 2 points, which was closer than his nearly 6-point statewide deficit. On the new map, only 14 of 38 districts are more Democratic than the state (sticking with the TX-23 example, Biden lost the new version by over 7 points). Map 3 compares the current and adopted plans.

Map 3: Texas districts, 2020 vs 2022

Aside from Districts 15 and 28, Democrats are safe in all of their other districts. Republicans are safe in every red district, with the exception of TX-23. If our ratings are accurate, Texas would elect a 25-13 Republican House delegation next year, up from 23-13 in 2020.

West Virginia

Aside from a renumbering, West Virginia redistricting basically shook out as we expected. Rep. Alex Mooney (R, WV-2) seems to be the odd man out as his district, which runs from the eastern panhandle down to Charleston, was essentially split in half. He is from the former part, and seems poised to run in a primary against Rep. David McKinley (R, WV-1) in the new northern district. Though McKinley is less of a strident conservative, he currently represents more of the new district, so would seem to have the upper hand.

Meanwhile, in the southern half of the state, Rep. Carol Miller (R, WV-3) should not have much to worry about. Both districts are Safe Republican.

Conclusion

Among the states we discussed in this article, Republicans will probably emerge with a net gain of a few seats. If they defeated Axne in IA-3, the loss of a GOP-held seat in West Virginia would essentially cancel that gain out. With that trade, it seems the GOP will still come out several seats ahead between North Carolina and Texas.

This would not represent a drastic change, all things considered, but to flip control of the chamber, Republicans will not need a very large net gain, either — they just need to win 5 more seats than they did last year. If Biden’s poor approval ratings persist, House Republicans’ goal of taking back the majority will be even easier.

While we’ll likely dissect the gerrymander that Illinois Democrats put into place very soon, it will be interesting to see what type of approach their counterparts in New York take — aside from the Land of Lincoln, the Empire State is Democrats’ biggest prize. Democrats can still gerrymander there, but a statewide ballot issue that would have eased their path failed last week. Could the currently-sour national environment prompt Democratic mappers to trim their sails, and opt for “safer” maps that imperil fewer Republicans?

With Republicans needing fewer factors to fall into place for them, Democrats are facing some pivotal geographic choices in several states.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.