Breaking Down North Carolina and Pennsylvania’s New Maps

A Commentary J. Miles Coleman

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— North Carolina and Pennsylvania are 2 closely-divided states where the redistricting process this cycle ultimately fell to Democratic-controlled state courts.

— Democrats seem likely to gain at least 1 seat out of North Carolina, although the relatively favorable map that they got will only be in place for the 2022 election cycle.

— As we expected, a GOP-held seat was eliminated as Pennsylvania’s delegation was forced to downsize, but some of its Democratic members, particularly in the eastern part of the state, will have their work cut out for them.

New maps in 2 competitive states

North Carolina and Pennsylvania are 2 of the handful of most competitive states in the nation. Each has a high-profile open-seat Senate race this year and were roughly mirror opposites for president in 2020, with Joe Biden winning Pennsylvania by about 1.2 points and Donald Trump winning North Carolina by about 1.4 points. Following court intervention in each state, both states finalized their congressional maps last week (barring U.S. Supreme Court intervention, which Republicans in both states are seeking).

The new political geography of each of these states merits a close look.

North Carolina settles on a (pretty fair) 2-year map

In the Old North State, debates over 3 topics seem to persist: college basketball, barbecue sauce, and redistricting. While the last item may, admittedly, not be the most enjoyable of the trio, North Carolina is truly in a category of its own — it is the only state that used 3 sets of congressional maps in both the 1990s and 2010s.

True to that history, the post-2020 redistricting round was not easy. Ahead of the line-drawing session, legislators from the GOP majority cleverly announced that they wouldn’t consider racial or partisan data when mapping the districts. This may have given the mappers a veneer of impartiality, but it is not hard to memorize the state’s basic voting patterns. Sure enough, Republicans passed a map that gave Democrats only 3 solid seats on a 14-seat map.

As a result, the state Supreme Court, which has a narrow Democratic majority, reversed a ruling from a 3-judge lower court panel and overturned the original plan. The higher court’s justification was that Democrats were too disadvantaged. In response to the court ruling, legislative Republicans submitted a map that was more proportional — it included 6 Biden-won seats — but several of the districts were bizarrely shaped.

The state Supreme Court went with its own plan, which was drawn by special masters. In the 2020 presidential election, both major party nominees would have carried 7 seats, although it will be easier for Republicans to win a majority of the delegation — this seems an accurate reflection of the state as a whole.

Republicans are hoping the U.S. Supreme Court will get involved, but in the meantime, we are assuming the state court’s map stands. Some good news for Republicans, though, is that the court-drawn map will only be in place for a single cycle. Republicans have a fair chance at flipping the state Supreme Court this year, so they may benefit from more favorable circumstances after the 2022 elections and be able to re-impose their preferred partisan gerrymander.

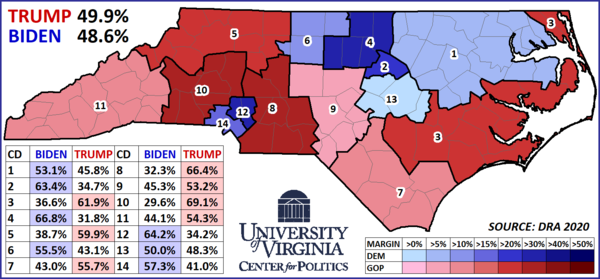

Map 1: 2022 North Carolina districts by 2020 vote

Something to note before we start our tour of the state is that the candidate filing deadline is tomorrow (Friday). While we won’t be able to account for any possible last-minute surprises here, we have a good general idea of the situation in each of the districts.

First, we’ll start by getting the Safe districts out of the way. Reps. Deborah Ross (D, NC-2) and Alma Adams (D, NC-12) retain districts in the Raleigh and Charlotte areas, respectively, that each gave the leading candidates on the 2020 Democratic ticket about 65% of the vote. Similarly, District 4, which includes the university cities of Durham and Chapel Hill, is the bluest district in the state — it is an open seat, and retiring Rep. David Price’s (D, NC-4) successor will almost certainly be chosen in the Democratic primary.

On the Republican side, districts 3 and 7 take up much of the state’s coastline and are Safe Republican. A decade ago, had this iteration of NC-7 been drawn, it would have been a gift to then-Rep. Mike McIntyre, one of the most conservative Democrats in the House. But several factors have worked to push NC-7 out of reach for Democrats. One factor is that the district includes the state’s fastest-growing county, Brunswick: it got that distinction, in large part, by attracting retirees, who have pushed the area rightward. Another change is that some of McIntyre’s most loyal constituents — the Lumbee Indians of Robeson County (in the bad Democratic year of 2010, he earned over 80% in some Lumbee-heavy precincts) — have since become Republican voters.

Robeson County’s current representative — Republican Dan Bishop — has been given a seat that, while secure for his party, is mostly new to him. Under the outgoing map, the territory between the Charlotte and Fayetteville metros was split horizontally between the districts 8 and 9 — that split is now more a vertical arrangement. Bishop’s current NC-9 begins in an upscale part of Charlotte (where he lives) and runs along the South Carolina border down to Robeson County. Though the seat was slightly altered for 2020, Bishop won the seat in a rare do-over election in 2019.

With his old seat essentially split in half, Bishop announced that he’d switch to the 8th District. While he currently represents the most populous county there, Union, 60% of the district is new to him.

In northwestern North Carolina, Rep. Virginia Foxx’s (R, NC-5) district is similar to what she currently has. NC-5 includes Forsyth County (Winston-Salem) and all of Boone (home to Appalachian State), but the area in between will routinely give Republicans over three-quarters of the vote — on balance, Trump was around 60% both times there.

District 10, which is just to the south of NC-5 and takes in the northern and western reaches of the Charlotte area, is even redder — it is the only district in the state where Biden took under 30% of the votes in 2020. Assuming they are reelected, Foxx and Rep. Patrick McHenry (R, NC-10), who were both elected in 2004, will be the most senior members of the Tar Heel delegation.

At the state’s western extreme, NC-11 is a Trump +10 seat with a controversial incumbent. Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R, NC-11) is an outspoken member of his party’s far-right wing, and his antics have drawn criticism from both the left and right. While the Republican-passed map kept his current district essentially unchanged, Cawthorn, in something of a surprise move, announced that he’d switch districts — his intention seemed to be to deny state House Speaker Tim Moore (R) a spot in Congress. But with the court-drawn map, switching seats would make little sense: Foxx and McHenry represent the only 2 adjacent districts. So he’s staying put in NC-11.

Not too surprisingly, Cawthorn has drawn several GOP opponents. State Sen. Chuck Edwards, the only state legislator who has filed for a promotion, is running as a conservative, but one who will keep more of a parochial focus than the incumbent has. In what’s made for an awkward situation, after Cawthorn announced his now-scuttled plans to leave the district, he endorsed local GOP chairwoman Michele Woodhouse. But even with Cawthorn staying put, Woodhouse has still filed to run. Democrats have several candidates in their primary, but this seat will be a tough lift for any nominee.

Now, let’s look at the districts that the Crystal Ball considers to be at least somewhat competitive.

Since 1992, the 1st District has been based in northeastern North Carolina, an area which is home to a sizable Black population. Unlike the other Democratic-leaning districts on the map, which center on large metro areas, NC-1 has a rural flavor and is not dominated by a single city. Historically, this has been solid Democratic territory — 3 of the state’s 4 most recent Democratic governors, including current Gov. Roy Cooper, were raised within the boundaries of the new 1st — but the district, which favored Biden by only 53%-46%, has become more competitive.

Visually, the center of the district is a handful of rural counties that span from the Roanoke Rapids area to the coast. In 2020, current Rep. G. K. Butterfield (D, NC-1), who has held this seat for almost 20 years, actually performed slightly worse in this part of the district than he did during the red wave of 2010.

Shortly after the legislature passed its original plan, which made his district even more rural and competitive, Butterfield announced his retirement. If that plan had stood, we would probably be calling this seat a Toss-up. But we are instead rating the open NC-1 as Leans Democratic. A switch of only 2 counties explains this rating.

Originally, the legislature kept basically all of Wayne County (Goldsboro) in the seat — a relatively large county, by the standards of eastern North Carolina, it is an inelastic Trump +12 county. The court-ordered NC-1 eschews Wayne County and adds most of Pitt County (Greenville). Biden carried NC-1’s portion of Pitt County by 14 points, which was actually a bit better than Barack Obama’s showing there in 2008.

Within the new 1st, Republicans usually carry a few less populous eastern counties, but Franklin County, just north of Raleigh, has become a key part of their coalition in the district. With demographics similar to the state as a whole, it voted for John McCain by less than 1 point in 2008 — but by 2020, Trump earned 56% there. Why the change? Part of the answer may be that most of its growth has occurred in the southern part of the district, which bumps up against Raleigh’s Wake County. In short, it is voting more like an exurb. Like Brunswick County in NC-7, it is a reminder that population growth has not been a total net plus for state Democrats.

Still, we have been hard-pressed to find a recent statewide Democratic nominee who hasn’t carried the new NC-1. Popular Republican state Agriculture Commissioner Steve Troxler, who won by nearly 8 points in 2020 (a landslide by state standards), lost the district by about 2 points.

Democrats have a few prominent candidates. State Sen. Don Davis is from the Greenville area, while former state Sen. Erica Smith represented a rural district. Smith ran in the 2020 primary for U.S. Senate, and was originally a candidate for that office again, but has dropped down. On the GOP side, Butterfield’s 2020 opponent — Sandy Smith, who ran as a strident Trump Republican — is running again, although she may face a crowded primary.

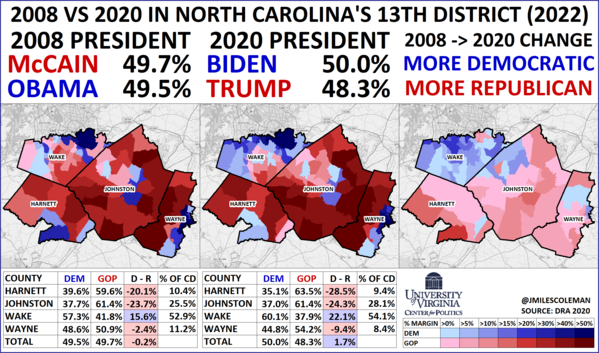

Unlike some of the lower-numbered districts in the state, which have long been associated with certain regions (NC-7, for instance, has been in the southeast since the 1930s), NC-13 has had a shifting identity since it first re-appeared after the 2000 census (North Carolina had a 13th seat for a few decades in the early 1800s). For the first decade of the 2000s, it was a blue seat that hugged the Virginia border and included pockets of Raleigh and Greensboro. Then, it was redrawn for 2012 as a mildly red Raleigh-area seat. It was reincarnated as similarly red Piedmont seat for 2018, before it was made even more Republican in 2020.

Under the court’s plan, NC-13 moved back to the Raleigh area, and is, politically, an evenly-divided seat. While the 2nd District includes much of the state capital city, the 13th takes in all or parts of fast-growing communities like Cary, Apex, and Garner. Johnston County, the only whole county within the district, provides a solid foundation for Republicans.

Though the new 13th is often a close district, over time, it has been moving more Democratic. As North Carolina voted red in 2020, the 13th went blue, but back in 2008, that positioning was reversed. According to our calculations, as Obama carried the state, he would have lost the new version of NC-13 by about 440 votes — this would have made it the third-closest McCain-won district in the nation, after the 2008 versions of PA-3 and NV-2. Map 2 illustrates the shifts in NC-13 since then.

Map 2: 2008 to 2020 in new NC-13

According to Politics1, an invaluable site that tracks down-ballot races, over a dozen Republicans are running in the primary. The Republican field includes former Rep. Renee Ellmers — who was a surprise winner in the 2010 GOP wave, but lost a redistricting-induced primary in 2016 — and Bo Hines, who has support from the Club for Growth. On a historical note, though Ellmers lost her 2016 primary, she was the first congressional candidate that Donald Trump endorsed as the presumptive GOP presidential nominee.

The Democratic field so far includes state Sen. Wiley Nickel, who was the first Democrat to announce a run in NC-4 when Price retired, but the 13th has some overlap with his current state Senate district. Former state Sen. Sam Searcy, who is from Wake County, is also considering a run.

While the marginal nature of the district may make it hard for Democrats to replicate Biden’s 2020 showing — especially in an environment like this — we’re starting it off as a Toss-up.

Just west of NC-13, NC-9 is a Republican-leaning district that we are keeping on the edge of the playing field. Five-term Rep. Richard Hudson (R, NC-8) is running here — though his home city of Concord wound up over in NC-12, Hudson has represented about 70% of the new 9th at some point or another over the last decade. Democrats have a credible candidate in state Sen. Ben Clark, who has represented the Fayetteville area since 2012, but the district supported Trump 53%-45%.

Simply put, NC-9 is not as red as the adjacent 7th or 8th districts, but it is still a reach for Democrats. The red anchor for Republicans in NC-9 is Randolph County, which makes up 19% of the district. Originally settled by Quakers in the 1700s, this square-shaped county gave Trump almost 80% of the vote, and a 41,276 raw vote margin, his second highest in the state. In 2008, McCain “only” got about 70% there, so Randolph County is a good illustration that Trump’s gains in already-deep red areas helped him carry the state. Biden carried the rest of the district by about 5 points.

One of the biggest losers under the map that legislative Republicans passed was first-term Rep. Kathy Manning (D, NC-6), who currently represents a tidy district in the Triad. Under the GOP-drawn plan, Guilford County (Greensboro) was cracked among 3 red districts. Under this plan, Manning retains all of Guilford County, but trades out much of her Forsyth County (Winston-Salem) holdings for redder turf along the Virginia border. As a result, Biden’s margin in the district is halved, going from 24 percentage points to 12.

The new NC-6 is still a largely favorable arrangement for Manning, but if a Republican can energize voters in Rockingham County, and keep the Democratic margins down in Guilford County, this could be a Republican target in a wave year — we’ll call it Likely Democratic for now.

Over the last year or so, something that was very much on the minds of North Carolina politicos was where the state’s newly-awarded 14th District would appear. Under the court’s plan, the inaugural NC-14 will be a Charlotte-area seat. Within Mecklenburg County, the 14th District includes all of the upscale “Wedge” — the nickname that political enthusiasts have given the formerly-Republican southern suburbs of the city — and it goes west to include the Charlotte Douglas airport. Further west, the 14th also includes most of exurban Gaston County, although Mecklenburg County makes up close to 75% of the district.

A decade ago, Bishop (who lives in the Wedge), could have just stayed put: the 14th would have given Obama less than 52% in 2008, so it would have been manageable for a Republican running in a Democratic midterm year. But while Gaston County has remained politically consistent since 2008, Biden took Obama’s 56%-43% showing in the Mecklenburg County part up to 64%-34%.

Overall, Biden took 57% in NC-14, which actually makes it bluer than Manning’s NC-6. Democrats also have a strong recruit in state Sen. Jeff Jackson, who was initially running for Senate but dropped out in December. Jackson is well-known in the area, and is close to a prohibitive favorite in the primary. For the general, we’re starting NC-14 as Likely Democratic.

Pennsylvania’s 2018 map carries on (but with 1 less seat)

Redistricting in Pennsylvania fell to the state Supreme Court after Gov. Tom Wolf (D-PA) and a Republican legislature couldn’t agree on a plan. The court ordered a redraw of a Republican gerrymander in 2018. Four years later, and after reviewing several submissions, it should not be surprising that the court picked a plan that is similar to the map it imposed a few years ago.

Like North Carolina, the Pennsylvania court is in Democratic hands. One key difference, though, was that while the former was tasked with adding a new district, the latter had to eliminate one.

As the Crystal Ball noted in our redistricting preview, much of central Pennsylvania has seen sluggish, or even negative, population growth over the last decade — so it seemed likely a seat there would be eliminated. Sure enough, on Monday, Rep. Fred Keller (R, PA-12) announced his retirement. Keller’s seat, based in the north-central part of the state, was partitioned among 3 other solidly red districts (PA-9, PA-13, and PA-15).

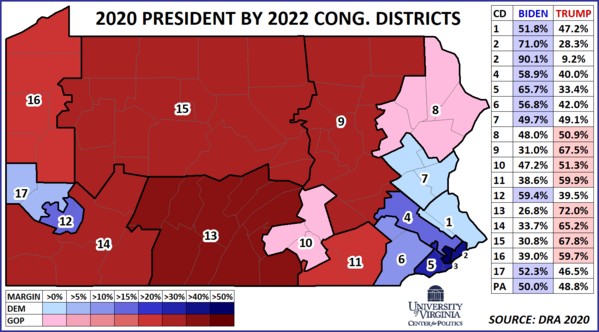

Map 3 shows the new Pennsylvania districts colored by the 2020 presidential vote. The filing deadline for Pennsylvania is coming up soon, on March 15, so there may be some new candidacies that emerge between then and now, but here’s how we’re initially rating the new districts.

Map 3: 2022 Pennsylvania districts by 2020 vote

Starting numerically, Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R, PA-1) is a good bet for 2022. Though his PA-1 takes in more of Montgomery County, it is still “the Bucks County seat.” Even though every Democratic presidential nominee has carried Bucks County since 1992, the Democrats’ congressional nominees have only won its district twice, in 2006 and 2008 — even as the district flipped blue in 2006, it was the non-Bucks portion of the seat that delivered a narrow win for Democrats.

Bucks County’s proclivity for ticket-splitting was on full display in 2020: Trump took 47% in the district while Fitzpatrick took 57%. Though Fitzpatrick may have another underwhelming primary showing — he was renominated with less than 70% of the vote in both 2018 and 2020, and has some intraparty opposition this time — we view the general election as Likely Republican.

Districts 2 and 3 are both located within Philadelphia proper and are the safest Democratic seats on the map. Districts 4 and 5 are less blue, but should reelect their Democratic incumbents, Madeleine Dean and Mary Gay Scanlon, respectively, without much fanfare. District 4 centers on Montgomery County but reaches north into Berks County, which makes for an interesting contrast. At its southern end, PA-4 includes Gladwyne, a community closer in to Philadelphia that was named the 6th richest ZIP code in America in 2018, but its Berks portion has more of a small town feel — when districts need to pick up population, such curious pairings are sometimes inevitable. Though it takes parts of Montgomery and Philadelphia counties, PA-5 is still primarily a Delaware County seat.

District 6 may be the least changed district on the map: its Bucks County portion adds about 12,000 residents from the Reading area, but it is otherwise a district dominated by Chester County. Rep. Chrissy Houlahan won the seat by 18 points in 2018, and held on by 12 points in 2020. That was still comfortable, but it was 3 percentage points less than Biden’s margin in the district. While it may be encouraging for Republicans that Houlahan, as an incumbent, underperformed Biden, in 2018, Democrats flipped 5 state House seats in Chester County and retained them all in 2020 — a sign that the area’s newfound Democratic allegiance is holding. We’ll call PA-6 Likely Democratic to start.

While Democrats are relatively secure in the Philadelphia area, the turf just to the north is a different story.

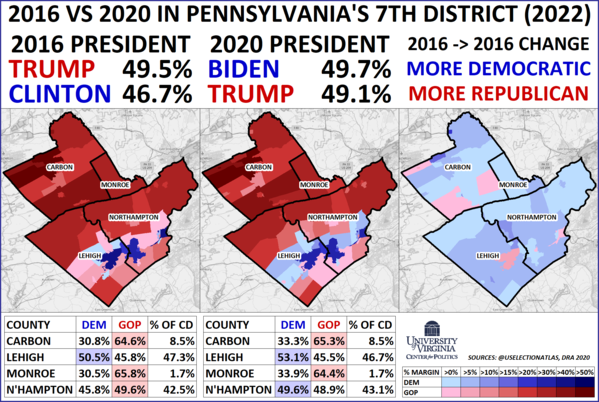

Of the 4 Democratic women in the Pennsylvania delegation who were first elected in 2018, Rep. Susan Wild (D, PA-7) is the most vulnerable. Her district is based in the Lehigh Valley, which tends to mirror the state as a whole. Lehigh (Allentown) and Northampton (Bethlehem) counties, together, make up 90% of the district. For the other 10%, Wild traded out blue parts of Monroe County (namely around Stroudsburg) for Carbon County, one of the state’s erstwhile swingy counties that is solid red today.

With the changes in PA-7, Biden would have only carried the new district by half a percentage point. In 2020, if Wild kept her same performance in Lehigh and Northampton counties but matched Biden in the new parts of the district, she would have lost by about 1,800 votes. Her 2020 opponent, Lisa Scheller, is running again and has racked up endorsements from several Republicans in the delegation, although she may not monopolize the primary. We are starting this race out as a Toss-up.

One key constituency in this race could be the area’s Hispanic community. Allentown, the largest city in the district, is now majority Hispanic by composition: since 2010, the Hispanic share of the city has risen from 43% to 54%. While we have often discussed Trump’s gains with minorities in the context of Sun Belt states, similar shifts showed up in the northeast. As Map 4 shows, while Biden flipped the district, he performed 7 percentage points worse than Hillary Clinton in Allentown (the pink on the 3rd image next to the “Lehigh” label). Had he matched Clinton there, Biden would have carried the district by almost 1.5% instead of half a point — that doesn’t sound like much, but in a district split this evenly, every vote counts.

Map 4: 2016 to 2020 swing in new PA-7

In the northeastern corner of the state, Rep. Matt Cartwright (D, PA-8), who is from Scranton, actually sees his Obama-to-Trump district get a bit bluer (he picked up Stroudsburg from Wild). While President Biden took 47% in his native district in 2020, Cartwright won 52%-48%. Though Cartwright has a proven record of earning crossover support, PA-8 is still a district that Trump carried by 3 points. As with Scheller in PA-7, 2020 Republican nominee Jim Bognet is seeking a rematch. We are also calling this a Toss-up, but in the longer term, the demographics are more favorable to the GOP here.

Considering the changes between districts 7 and 8, the court gave Cartwright some help — but perhaps not enough for him to actually win — at the expense of Wild, who could not afford to lose too many blue precincts. From a purely partisan perspective, some Democrats may have preferred to see Wild’s seat strengthened but Cartwright’s weakened — that way, it would be more likely they’d come out of this cycle with at least 1 of those seats. Instead, Republicans have a decent shot at claiming both, although in a favorable Democratic cycle, both could feasibly go blue later in the decade even if Democrats lose them this year.

Moving into south-central Pennsylvania, the duo of PA-10 and PA-11 is largely unchanged.

The current configuration of PA-10 was new for 2018: it takes in Harrisburg’s Dauphin County, its neighboring communities that are across the Susquehanna River in Cumberland County, and reaches south to grab half of York County — each county makes up almost exactly one-third of PA-10’s population. Trump carried the 10th 53%-43% in 2016, but that showing fell to 51%-47% in 2020.

The good news for Rep. Scott Perry (R, PA-10), who faced close races in 2018 and 2020, is that he can breathe a bit easier this year. His 2020 opponent, former state Auditor Eugene DePasquale, announced he’d pass on a rematch. Though Perry is perhaps a bit too conservative for the area — within the ranks of the House Freedom Caucus, of which he is a member, he holds a relatively marginal district — this is looking very much like a reach pickup opportunity for Democrats. We’re starting it as Likely Republican.

Though it takes in the other half of York County, the focal point of PA-11 is Lancaster County, which now has well over a half a million residents. This is a safe seat for Rep. Lloyd Smucker (R, PA-11), but it may have some longer-term potential for Democrats. One of the most historically GOP counties in the state (it was the home of the famous Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens), recent Republican presidential nominees have carried Lancaster County by 10%-20%, instead of the 30-point blowouts George W. Bush posted there.

If Democrats have some quibbles about how the Lehigh Valley was drawn, they should have nothing but praise for how the court handled the Pittsburgh area. Allegheny County, which contains Pittsburgh proper, will see open-seat contests for both its districts this year. PA-12, which includes all of the city itself, is the successor to the district from which longtime Rep. Mike Doyle is retiring — it was previously labeled “PA-18,” but the state now only has 17 seats. Rep. Conor Lamb (D, PA-17) is running for Senate and leaves behind a district that contains the area’s northern suburbs.

PA-17, which is a Trump-to-Biden district under the current map, is the more marginal of the duo. Rather than expanding outwards into redder turf, which seemed like a distinct possibility, PA-17 takes in about 50,000 more residents of Allegheny County (mostly from cities just south of Penn Hills). Importantly, PA-17’s new constituents broke 72%-27% for Biden — this pushes Biden’s margin in the new seat up to 6 points, and it would have even narrowly favored Clinton in 2016. As an open seat in a (likely) red-tinged year, though, we’re calling this a Toss-up.

PA-12 is a few notches less blue than the old PA-18, as it is now pushed out to Westmoreland County, but it went for Biden and Clinton by about 20 points apiece.

Finally, districts 14 and 16, which touch the state’s western border, may have been competitive at some points in the early 2000s, but should easily stay in GOP hands this year.

Conclusion

Democrats have continued to benefit from state judicial intervention against Republican gerrymandering in North Carolina, although that backstop may disappear in 2022, opening the door to a reinvigorated Republican gerrymander in 2024 and beyond. Keep this in the back of your minds when assessing the overall redistricting picture and the eventual 2022 results — the GOP may have some unrealized redistricting gains in North Carolina that they could cash in for 2024.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania — which has divided government — has what seems like a fair map imposed by the court, but one on which Republicans should very credibly target 3 marginal seats held by Democrats (PA-7, PA-8, and PA-17). In that, it’s similar to Michigan, where a new independent redistricting commission drew what also seems like a fair map where Republicans may benefit in the short term.

Overall, 44 of the 50 states now have maps in place. Currently, Democrats hold a 199-169 U.S. House edge in these states. Based on our ratings of the new districts in these states, 183 are rated at least leaning Democratic, 163 at least leaning Republican, and 22 as Toss-ups. So Republicans are “down” 6 seats and Democrats are down 16, although many Toss-ups would have had the same ratings had there been no redistricting this year. We are still waiting on House maps in Florida, Louisiana, Missouri, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.