Governors: Escaping Public’s Wrath Even as So Many Others Draw Ire

A Commentary By Louis Jacobson

State chief executives continue to get high marks from voters even as party leaders, Congress do not.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Virtually every measurement of public opinion shows that Americans are in a foul mood about their political leaders and institutions. But one group seems to have escaped this wrath: governors.

— State-level job approval polls from Morning Consult show that 92% of governors are “above water” with voters in their states — that is, they have higher approval ratings than they do disapproval ratings. With a handful of exceptions, the data from other pollsters back up the general pattern seen in the Morning Consult polling.

— The polling suggests that several Democratic governors who are considered particularly vulnerable in a Republican-leaning midterm environment have managed to put some distance between how voters see them and President Joe Biden, which could improve their chances of winning reelection.

— The reasons why governors seem to be faring relatively well in this sour environment may have to do with the nature of the most worrisome issues for voters today (which include a number of policies that governors don’t directly control, such as inflation) and relatively flush coffers due to federal aid (which is sparing governors from having to make unpopular cuts or raise taxes).

The resilient popularity of governors

To say voters are in a sour mood today would be an understatement. Here are some data points:

— President Joe Biden’s most recent composite approval rating from FiveThirtyEight is about 14 points under water. That means that Biden’s disapproval rating exceeds his approval rating by 14 points.

— Gallup’s decades-old “right-track, wrong track” question — “in general, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the way things are going in the United States at this time?” — sits at 55 points under water.

— Congress’s most recent approval rating from Gallup is slightly worse, at 56 points under water.

— The Supreme Court’s most recent approval rating, according to Gallup, was 13 points under water.

— Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump, isn’t in office anymore, so pollsters don’t ask about his approval rating. But Trump’s most recent favorability rating — whether respondents view him favorably or unfavorably — is 13 points under water, according to FiveThirtyEight.

All in all, Americans are in a funk. Despite all that, however, Americans have little quarrel with their governors.

Almost every governor in the nation, regardless of party affiliation, has an approval rating above water at the moment, at least according to the most recent survey work published by Morning Consult, the only entity that conducts gubernatorial approval polls in all 50 states. (The data were released on April 28; the surveying was done during the first quarter of 2022 and is intended to capture enough voters in each state to produce statistically valid samples in each.)

The big picture from Morning Consult’s polling is that 46 of the nation’s 50 governors — an eye-popping 92% — have approval ratings above water. Another governor, Pennsylvania’s Tom Wolf (D), has evenly matched approval and disapproval ratings. That leaves only 3 governors who were under water in their approval ratings: Democrats Tony Evers of Wisconsin, David Ige of Hawaii, and Kate Brown of Oregon.

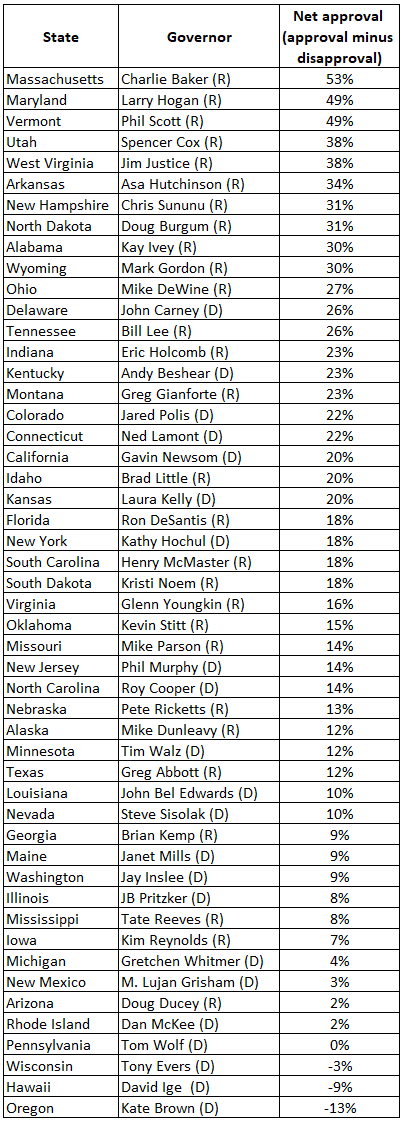

Here’s a list of the 50 governors, ranked in descending order by net approval (approval minus disapproval):

Table 1: Net approval of governors, according to Morning Consult

This pattern has been consistent: In 2019, we found a similar overperformance among governors compared to Trump, who was then in the White House.

One way to look at the current list is within a partisan context: Republican governors tend to have stronger net approval ratings than Democratic governors do. There’s something to this. The top-ranking Democrat on this list, Delaware’s John Carney, is tied for 12th in net approval, below 11 Republicans. And as noted, the 3 governors whose approval ratings are under water are all Democrats.

Still, it would be unwise to simply chalk up these numbers to Republican dominance. The healthy approval ratings are too widespread to be a purely partisan phenomenon.

About half of the Democratic governors have net approval ratings in the double digits. And of the Democrats who will have to face the voters in 2022 and have competitive races, several are comfortably above water. Kansas’s Laura Kelly is net +20, Nevada’s Steve Sisolak is net +10, and Maine’s Janet Mills is net +9. Getting voters to fire an incumbent who is viewed as doing a credible job is not impossible, but it’s harder than beating an incumbent whose numbers are poor.

Notably, all but 3 Democratic governors — Brown, Ige, and Rhode Island’s Dan McKee — are polling as well or better than Biden is in their own state. (We know this because Morning Consult also polls Biden’s approval in every state.)

This distance from Biden is important for sitting Democratic governors because it demonstrates that they can separate their records from Biden’s, possibly giving them enough space to survive in a tough political environment.

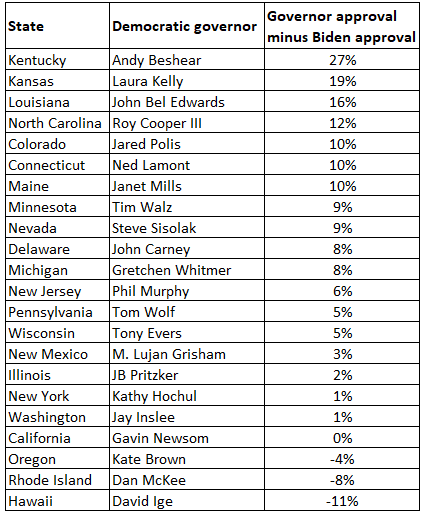

Here’s the rundown:

Table 2: Democratic governors’ approval minus Biden approval in their state

Of the 22 Democratic governors currently serving, 18 (or 82%) are beating Biden’s current approval rating, and one, California’s Gavin Newsom, is matching it.

Of the 18 Democratic governors who are beating Biden’s approval rating, 14 are doing so by at least 5 percentage points. And at least 6 of those 14 could really use the bump, because they are running in competitive 2022 races. This list includes Kelly, Mills, Sisolak, Evers, Tim Walz of Minnesota, and Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan.

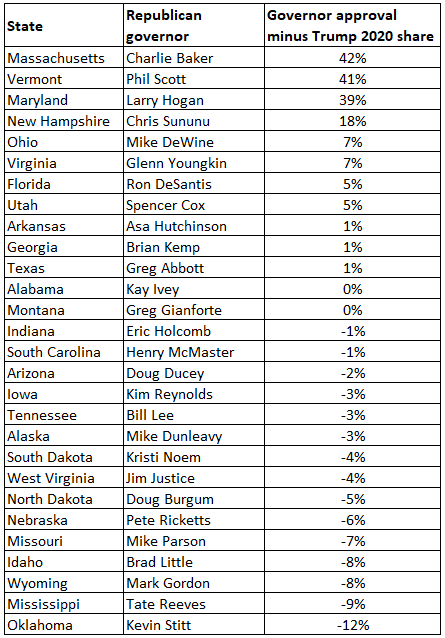

By contrast, while many Republican governors remain in good shape, many have approval ratings below the percentage of votes won by Trump in their state in 2020. (We’re using this as a proxy for Trump’s current approval rating, which pollsters do not measure.)

Table 3: Republican governors’ approval minus Trump 2020 percentage in their state

In all, of the 28 GOP governors currently serving, only 11 are beating Trump’s numbers from 2020 (or 39%). Of the 8 GOP governors beating Trump by at least 5 percentage points, 4 are northeastern moderates who won in blue states, and 2 more have vocal critics to their right in their states, Ohio’s Mike DeWine and Utah’s Spencer Cox. The 2 others are Florida’s Ron DeSantis and Virginia’s Glenn Youngkin.

Perhaps the first quarter of the year, when the Morning Consult polls were taken, was an overly optimistic time for Democratic governors, and as Election Day approaches, the grinding dissatisfaction for Biden will become so massive that the governors’ apparent distance from the president will vanish.

Or maybe Morning Consult’s methodology is off-base. However, other polls that have looked at gubernatorial approval this year show a broadly similar picture.

Utah’s Cox, Maryland’s Larry Hogan, Vermont’s Phil Scott, Arkansas’s Asa Hutchinson, New Hampshire’s Chris Sununu, Tennessee’s Bill Lee, Indiana’s Eric Holcomb, Kentucky’s Andy Beshear, and Colorado’s Jared Polis all have net approval ratings of at least +20 in both independent polls and in Morning Consult.

Other governors with net approvals in the double digits in both Morning Consult and an independent poll include Kansas’s Kelly, Florida’s DeSantis, Connecticut’s Ned Lamont, New York’s Kathy Hochul, New Jersey’s Phil Murphy, and North Carolina’s Roy Cooper.

There were, however, some governors who have received strongly divergent net approval ratings from Morning Consult and independent polls. Two endangered Democrats fared notably better in independent polls: Michigan’s Whitmer, who notched +18 net approval, compared to +4 in Morning Consult, and Wisconsin’s Evers, who was 1 of only 3 governors under water in the Morning Consult poll yet managed a +9 net approval in an independent poll.

Meanwhile, a few governors had weaker approval metrics in independent polls than in Morning Consult. Two were Republicans: Texas’ Greg Abbott (+2, compared to +12 in Morning Consult) and Oklahoma’s Kevin Stitt (+3, compared to +15 in Morning Consult). A couple of others were Democrats: California’s Newsom (+1, compared to +20 in Morning Consult), and Minnesota’s Walz (even, compared to +12 in Morning Consult). So while the Morning Consult polls were generally consistent with what other pollsters have found, there are differing findings in a number of states.

Overall, and if the Morning Consult numbers are credible enough to be trusted, the obvious question is: Why are governors coming out relatively unscathed despite the electorate’s widespread frustrations? I have a few thoughts.

One reason could be that many of the most troublesome concerns for voters today fall on the doorsteps of federal officeholders, rather than governors. The most important of these at the moment is inflation, something that governors have little power to influence (with the possible exception of gas prices, which can be reduced to some degree through state-level gas tax holidays). Other urgent issues that need to be tackled by the federal government rather than governors include immigration and international insecurity stemming from Russia’s war in Ukraine. A looming issue that could become very significant for governors is abortion, given the possibility that the Supreme Court could give the states more leeway to limit or even ban the procedure in a decision expected soon.

It’s true that governors were on the hot seat during the pandemic, faced with difficult policy-setting dilemmas between protecting the public’s health and securing continued economic activity. But the rates of hospitalization and death from the coronavirus have headed downward during the first half of this year, so governors have gotten a bit of a respite from public ire recently.

Meanwhile, other key issues animating voter anger today are handled at a lower level. Frustration over crime is largely an issue for mayors and city council members to handle, while fights over school policy usually fall to school boards and local education officials.

Perhaps the unsung reason for the paradoxically strong gubernatorial approval pattern today is the state and local government funding included in the American Rescue Plan, the coronavirus relief package passed with only Democratic support during the early days of Biden’s term.

While this measure has attracted some retroactive controversy in recent months as its inflationary effects have become more widely appreciated, the legislation handed out large sums of money to state and local governments that have made every governor’s job vastly easier.

If you harbor any doubts about the impact that a bad budget year or two can have on governors’ electoral prospects, just look at the 2002 election cycle. The state budget deficits during that election cycle were considered to be the worst in 50 years, forcing governors to either raise taxes, make cuts to popular programs, or both. Analysts said the budget crisis emerged from the post-dot-com bubble and post-9/11 recession, producing a hangover from heavy spending commitments that began during the robust economy of the 1990s.

In the 2002 elections, party control flipped in half the races on the ballot — a bloodbath that hobbled both parties, even in states where one party was dominant. Most of the governorships that flipped were open seats, but 4 sitting governors were ousted.

“For sure, state budgets are in a far better position” today, said Lucy Dadayan, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. Dadayan added that the federal aid is the primary reason for this, which suggests that the overflowing treasuries in the states might be only temporary. But they should remain healthy through the election, which could help incumbents’ prospects in November.

The irony, then, may be that Biden exacerbated his own approval woes by pushing to pass the American Rescue Plan, but simultaneously bolstered the ability of Democratic governors to withstand the Republican tide this year. We’ll have a better idea whether this irony becomes reality in November, when the gubernatorial votes are counted.

Louis Jacobson is a Senior Columnist for Sabato’s Crystal Ball. He is also the senior correspondent at the fact-checking website PolitiFact and is senior author of the Almanac of American Politics 2022. He was senior author of the Almanac’s 2016, 2018, and 2020 editions and a contributing writer for the 2000 and 2004 editions. |

See Other Political Commentary.

See Other Commentaries by Louis Jacobson.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.