The Dwindling Crossover Governorships

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik and J. Miles Coleman

Sununu’s retirement, other factors could reduce the number of split presidential/gubernatorial results.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Despite an increasing correlation between presidential and down-ballot results, there are still nine governors who govern states that their party did not win for president. That means there is a higher percentage of crossover governors than crossover members of the Senate and House.

— Still, the number of crossover governors was higher in the recent past.

— While there are lots of moving pieces, including what happens in the 2024 presidential election, we could see even more of a decline in the number of crossover governors in this cycle’s gubernatorial elections.

Assessing the crossover governorships

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu’s (R) announcement last week that he will not seek a fifth two-year term as the Granite State’s governor gives Democrats a key takeover target next year. But his departure might also help reduce the dwindling number of “crossover” state governors.

We often note the number of House and Senate seats where the winner of the district or state is of a different party than the party that won the district or state for president in the most recent election. There is a greater share of crossover governors than crossover House and Senate members, but the number of crossover members in all three categories has been declining.

Setting aside the three nominal independents who caucus with Democrats in the Senate — Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, Angus King of Maine, and Bernie Sanders of Vermont — there are just five “crossover” senators out of the 100 total. Two Republicans represent states Joe Biden carried in 2020 — Susan Collins of Maine and Ron Johnson of Wisconsin — and three Democrats represent Donald Trump-won states: Jon Tester of Montana, Sherrod Brown of Ohio, and Joe Manchin of West Virginia. The fact that all three of those Democrats are on the ballot in 2024 while neither of those Republicans are helps explain the Republicans’ golden opportunity to flip the Senate this cycle.

To put it in historical perspective, there were 24 “crossover” senators out of 100 immediately following the 2004 election and 21 immediately following the 2012 election.

In the House, there are just 23 members who hold crossover seats: 18 Republicans and 5 Democrats. That imbalance gives Democrats an opportunity of their own to win back the House this cycle. Likewise, this number has generally been declining — there were 59 crossover members elected in 2004 and 26 elected in 2012 (the House became considerably more sorted on presidential party lines in that election/redistricting cycle and has basically stayed so ever since).

The governorships are not as sorted by presidential partisanship as the House and Senate, although it seems quite possible that they will be more sorted following 2024 than they are now.

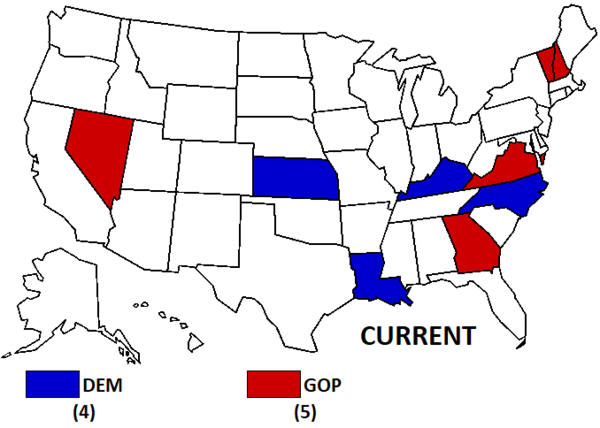

As shown on Map 1, 9 of the 50 governorships are currently held by a governor whose party is different than the state’s presidential winner in 2020.

Map 1: Current crossover state governorships

There are five Republicans in Biden-won states, and there are four Democrats in Trump-won states.

Relatively speaking, governorships are likelier to fall in the crossover category than House and Senate seats — 18% of the governorships are crossovers, whereas just 5% of the House and the Senate are. Governors likely have a little more ability to separate themselves from national political factors, and sometimes they are out of step from their national parties — but in-step with state electorates — on important issues. For instance, Gov. Phil Scott (R-VT) is supportive of abortion rights, while Gov. John Bel Edwards (D-LA) is not.

Still, just like with the House and Senate, the amount of gubernatorial crossover has been declining over time.

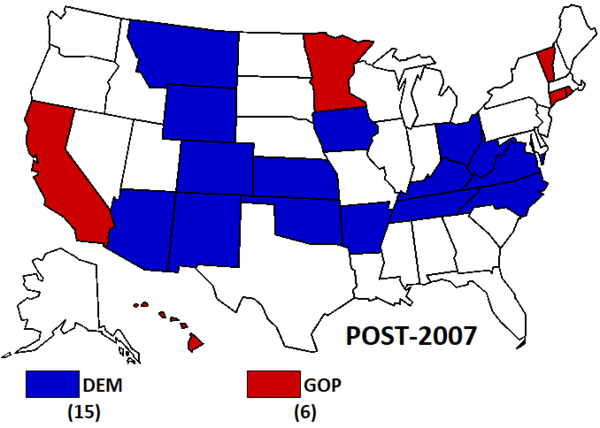

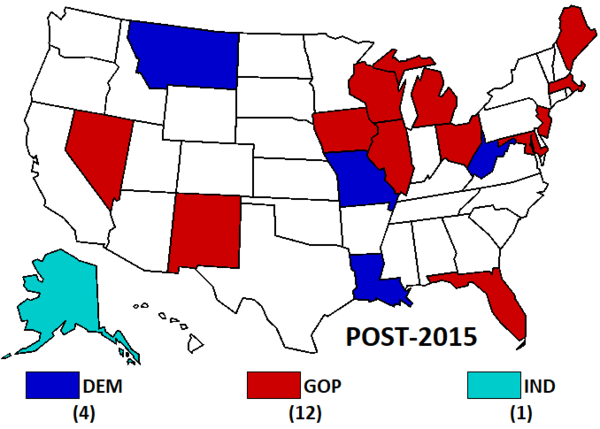

Let’s take a look back at how things stood after the 2007 and 2015 gubernatorial elections, respectively. Those elections, like the ones this year, took place three years after the most recent previous presidential election. And like the 2020 presidential election, both the 2004 and 2012 elections were close at the national level — all three were decided by between 2.5-4.5 points in the national popular vote.

Map 2: Crossover gubernatorial control following 2007 elections

Map 3: Crossover gubernatorial control following 2015 elections

As the maps show, there was considerably more crossover at the gubernatorial level in these past two periods than there is now: 21 crossover governorships following the 2007 elections and 17 following 2015. One can see some ancestral down-ballot lineage on these maps, as Democrats were much stronger 15 years ago in Greater Appalachia than they are now, for instance. But some of this lineage remains, such as with Republican success in Vermont and New England more generally. Red presidential states Kentucky and Louisiana have elected Democratic governors in the recent past, and the party still holds them as of this moment.

One thing that likely contributes to the greater amount of crossover at the gubernatorial level is that most governorships are elected in non-presidential elections — just 9 of the 50 states hold their gubernatorial elections only in years concurrent with the presidential election (Delaware, Indiana, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Utah, Washington, and West Virginia), although New Hampshire and Vermont have just two-year terms, so those two New England governorships are contested in both midterm and presidential years. An additional five states have odd-numbered gubernatorial elections (New Jersey and Virginia, last contested in 2021, and Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi, which are on the ballot this year). That leaves the lion’s share of all the governorships to be contested in midterm years.

Midterms can often produce big waves against the presidential party, and we see some of that aftermath on these maps. For instance, Democrats won the Ohio governorship for the only time since 1986 in 2006, but then lost it in 2010’s Republican wave. The anti-George W. Bush wave of 2006 also helped insulate some crossover Democrats: in 2002, Democrats in Arizona, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Wyoming all prevailed in close races but, as incumbents, each was reelected with more than 60% of the vote in 2006. Things got better for Republicans in 2010: They flipped several states that Barack Obama carried in 2008, most notably in the Midwest. In 2014, another red-tinted Obama midterm, most of those crossover GOP incumbents were reelected. There are also some odd circumstances reflected on this map, such as the 2003 recall of California Democratic Gov. Gray Davis leading to the two-term governorship of Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger (reflected on the 2007 map) and Republican Alaska Gov. Sean Parnell’s loss to a fusion independent/Democratic ticket led by former Republican Bill Walker in 2014 (reflected on the 2015 map).

That Republicans did not have that strong of an election in 2022 also helps account for the low number of crossover governors. They tried and failed to flip governorships in Biden-won battlegrounds Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, although they succeeded in another such battleground, Nevada. Still, the total number of crossover governorships dropped, as Democrats flipped Biden-won states Arizona, Maryland, and Massachusetts.

The 2023/2024 outlook

Overall, the number of crossover state governorships might decrease in 2024, although of course what happens in the presidential race will have an impact on the numbers. For instance, maybe the Republicans will win back key presidential battlegrounds like Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. That would create new crossover governorships in those states, because all currently have Democratic incumbents who won’t be on the ballot this cycle. A GOP victory for president in Georgia or Nevada would remove a crossover governorship because those states have Republican governors.

But let’s focus on the current crossover governors and see how the list might shrink.

This year, open-seat Louisiana is likely to flip to Republicans, and that state is going to vote Republican for president in 2024 barring some radical and unforeseen realignment over the course of this election cycle. Republicans also would like to flip Kentucky, but we continue to see Gov. Andy Beshear (D) as a small favorite there. A couple of recent polls by the respected Republican firm Public Opinion Strategies showed Beshear up 10 points in June and 4 points in July. One could argue that the race is tightening — although the polls had different sample sizes and were conducted for different clients, as the Lexington Herald-Leader noted in a story on the surveys — but we also think it’s notable that the only recent public polling in the race has been from Republicans, and none of those polls has shown the popular Beshear trailing. Still, this is another opportunity for the crossover list to shrink this year, as Kentucky, like Louisiana, is a lock to vote Republican for president.

Next year, Democrats will be defending an open seat in North Carolina. Since 1992, Republicans have only won one gubernatorial contest there (2012), while Democrats have only claimed the state’s electoral votes once (2008). Still, we rate the 2024 North Carolina gubernatorial race as a Toss-up, as margins are often close in the state — it could very feasibly break the same way for president and governor. Meanwhile, in New Hampshire, the open seat is now a Toss-up thanks to Sununu’s aforementioned retirement. That state is likelier than not to vote Democratic for president — if Democrats sweep, that would eliminate another crossover governorship. If Phil Scott retires in Vermont, the Democrats could also eliminate a crossover governorship there. In fact, there is a possibility that Democrats could hold all six New England governorships at the same time starting in 2025 — they already hold the other four, and could win New Hampshire and Vermont as open seats (a Morning Consult poll released this week ranked Scott as the nation’s most popular governor, and we seriously doubt he’d actually lose reelection if he sought another term).

We don’t believe Democrats have ever held all the New England governorships at once since the founding of the GOP in the 1850s — correct us if we’re wrong, but we went back and looked and couldn’t find such an instance. This is despite the fact that the region is heavily Democratic at the federal level: Democrats have won all six states in each of the last five presidential elections; they currently hold all of the region’s House seats; and Susan Collins of Maine is the region’s only Republican senator. On a similar note, if Republicans sweep both Louisiana and Mississippi this year and flip North Carolina in 2024, they will hold the governorships of all 11 formerly-Confederate states concurrently for the first time since Reconstruction. During the 20th century, Georgia only had Democratic governors — and since the Peach State flipped red in 2002, combinations of Arkansas, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia have kept Democrats alive in the South.

The other crossover governorships are not up until 2025 (Virginia, which will be an open seat because Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin by law cannot run for reelection) or 2026 (Republican Gov. Brian Kemp of Georgia and Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly of Kansas will both be term-limited, while Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo of Nevada is eligible to run for a second term).

So while gubernatorial results and outcomes seem to mirror presidential partisanship less than federal races do, the overall trend of increasing partisan consistency up and down the ballot could be a theme of this cycle’s gubernatorial races.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.