Senate 2022: An Early Look

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik

Democrats may ultimately have a better shot to win the Senate than the House in two years, although winning either will be challenging.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Democrats may have a better chance of winning the Senate in 2022 than holding the House, even if Democrats lose both Georgia special elections in January.

— The president’s party often struggles in midterms, which gives the GOP a generic advantage in the battle for Congress.

— The Republicans’ three most vulnerable Senate seats may all be open in 2022.

Our (very early) Senate assessment

Here’s a hot take as we look ahead to the 2022 midterm: Democrats may have a better chance of winning a Senate majority than a House majority in the next national election.

That is not to say Democrats have a great chance of winning a Senate majority — they don’t, particularly if Republicans hold the two Georgia Senate seats in a Jan. 5, 2021 runoff. Rather, it suggests that the Democratic Senate path might be more plausible than the Democratic path in the House, given looming redistricting and reapportionment and the history of presidential party House losses in midterm elections.

Since the Civil War, the president’s party has lost ground in the House in 37 of 40 midterm elections, with an average loss of 33 seats per election. Additionally, and as Sean Trende of RealClearPolitics recently observed, Democrats seem likely to lose seats through the decennial reapportionment and redistricting process once new House seat allocations and district lines are in place for the 2022 election.

With Democrats likely to hold a slim majority in the low 220s in the next House (218 is needed for a majority), Democrats could enjoy a good political environment but still lose their majority. That’s because Republicans are only going to need a single-digit-sized net seat gain to flip the chamber, and they have a stronger hand to play in redistricting across the nation than Democrats do.

In a bad environment, Democratic House losses could be severe, particularly if the party’s recent gains in highly-educated suburban areas erode with Donald Trump no longer in the White House.

If 2022 turns out to be a bad Democratic year — as it has been for the president’s party in each of the last four midterms — the Senate would remain Republican.

But there are sufficient Democratic targets for the party to win a narrow Senate majority if the political environment is not a burden.

Senate midterm history is not quite as bleak for the presidential party as the House history is. Yes, the president’s party often loses ground in the Senate in midterm elections, but the losses are not as consistent: Since the Civil War, the president’s party has only lost ground in the Senate in 24 of 40 elections, with an average seat loss of roughly 2.5 per cycle.

This speaks to the nature of the Senate, where only a third of seats are up each cycle (it’s also worth noting that Senate popular elections only started nationally in 1914, so this long timeframe covers the pre-election period, when state legislatures elected senators). If we restrict the history just to the post-World War II era, the presidential party Senate losses in midterms are higher, 3.5 seats on average, with the president’s party losing ground in 13 of 19 midterms. (These figures are calculated based on the Brookings Institution’s Vital Statistics on Congress.)

Still, there are exceptions to the usual presidential party Senate losses. Two years ago, for instance, Republicans actually netted Senate seats during the 2018 cycle despite above-average losses in the House — this was due in large part to the Democrats having to defend 26 of the 35 seats contested in 2018, including several in dark red Republican states. Republicans were on defense in 2020 and have thus far shed only a single net seat, but they have more defense to play overall than Democrats do in 2022.

Assuming Republicans hold the Georgia seats — we currently rate both as Toss-ups — the Senate would be 52-48 Republican, and Democrats would need to net two seats in 2022 to take control of the chamber with an assist from Vice President-elect Kamala Harris’ (D) tiebreaking vote. As we will explain, both sides have at least a few credible targets in the upcoming cycle.

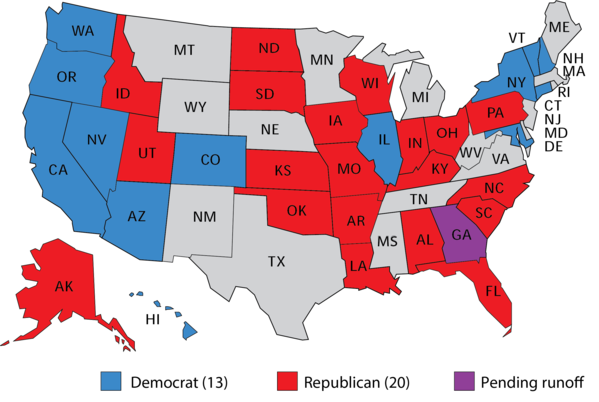

Map 1 shows the seats up in two years. Republicans are defending 20, Democrats are defending 13, and one other seat is not yet determined: The victor in the Georgia special election runoff, either Sen. Kelly Loeffler (R-GA) or the Rev. Raphael Warnock (D), will have to defend the seat again in 2022.

Map 1: 2022 Senate races

We aren’t going to release formal ratings of these races yet, but let’s go through them in three categories: Not Competitive, Potentially Competitive, and Probably Competitive. These categories only apply to the general election in each state.

Let’s start with the longest list: The races we do not see as competitive.

NOT COMPETITIVE: 15 R, 9 D

Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Missouri, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Washington

Right off the bat, we feel comfortable suggesting that roughly two-thirds of the 2022 Senate races (24 of the 34 on the ballot) seem like locks for the current party that holds these seats. None of these states were particularly close in the 2020 presidential election: Iowa, which gave Trump an eight-point victory, was the closest. Whether the Hawkeye State is competitive or not may depend on whether state institution Chuck Grassley (R), who has served in the Senate since 1981, decides to run for another term, although Republicans likely would be favored to hold the seat in any event given the state’s rightward turn over the last four statewide elections.

Hypothetically, strong challengers could shake up some of these races. For instance, popular term-limited Gov. Larry Hogan (R-MD) could threaten Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD), although Hogan has not suggested he is interested in running. Additionally, and despite what early polls might indicate, Van Hollen ultimately would be favored over any Republican, we believe — in federal races, Maryland is just too Democratic of a state.

Beyond Grassley, other octogenarians considering whether to run again are Sens. Richard Shelby (R-AL) and Patrick Leahy (D-VT), though there would be little doubt about their respective parties holding their seats if they became open. Leahy remains the only Democrat ever elected to the Senate from Vermont – remember, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) is still technically an independent. But Vermont has gone nearly two decades since one of its senators caucused with the Republicans: Sen. Jim Jeffords left the GOP in 2001 and became an independent who caucused with the Democrats. Sanders won election to the Senate after Jeffords retired in advance of the 2006 election.

Once Kamala Harris resigns from her seat to assume the vice presidency, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) will appoint a Democrat to replace her in the Senate. There will be no special election, as Harris’ seat is on the ballot for a regular election in 2022. The last two Senate elections in California, 2016 and 2018, have featured two Democrats in the general election as a result of the state’s top-two primary system.

Republicans did win a Senate seat in Illinois as recently as 2010; the state hypothetically could be close in a really bad Democratic year, but there are a lot of pieces that would need to fall into place for Republicans to really push Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-IL). Sen. Roy Blunt (R-MO) came close to losing to former Missouri Secretary of State Jason Kander (D) in 2016, but Kander has already said he won’t seek a rematch, and Democrats appear to be a spent force in Missouri (and Indiana, too, which was hotly-contested in 2016 but could very well be sleepy in 2022).

Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) had to win as write-in after losing a 2010 primary, and she prevailed in a three-way race in 2016. She may benefit from a new voting system in Alaska, just narrowly approved by voters, that replaces the state’s traditional party primary system with an all-party first round primary where the top four finishers regardless of party advance to a general election that utilizes ranked-choice voting. The bottom line here is that Murkowski now has an easy ticket to a general election, so she should be OK in 2022.

It may be that one or more of these races eventually end up in a more competitive category, but as of now we see the incumbent party strongly favored to hold every one of them.

POTENTIALLY COMPETITIVE: 2 R, 1 D

Colorado, Florida, Ohio

One of the signs about which way the wind was blowing in 2014, a great Republican midterm, was when then-Rep. Cory Gardner (R, CO-4) changed his mind and decided to challenge then-Sen. Mark Udall (D-CO) in early 2014. Gardner ended up beating Udall by two points as Republicans netted nine Senate seats. Gardner then lost in this year’s election by 9.3 points to former Gov. John Hickenlooper (D) — although Gardner did better than Trump, who lost the state by 13.5.

If 2022 is going south for Democrats, a sign may be if Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) is in trouble as he seeks a third term. The Democratic trend in Colorado is obvious, and Bennet may be able to hold on even in a 2014-style environment, particularly if he does not draw a strong opponent.

On the other hand, if Republicans end up struggling in 2022, perhaps that could endanger Sens. Marco Rubio (R-FL) or Rob Portman (R-OH) in states where Democrats have had several bad elections in a row. In Ohio, watch to see if Rep. Tim Ryan (D, OH-13), whose Republican-trending Northeast Ohio district is a prime candidate to be eliminated in redistricting, ends up finally running statewide after a decade and a half of rumors that he might take the plunge.

Overall, these are Senate races where we give a solid edge to the incumbent party to start.

PROBABLY COMPETITIVE 3 R, 3 D, 1 undecided

Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin

That leaves seven races where we are assuming a high level of competition, although not all of these races are guaranteed to be close in the end. Democrats are defending three of these states, Republicans are defending three, and one other — the Georgia special — will be decided in January. Let’s set that one aside and focus on the remaining others.

The six closest states in the presidential election all feature Senate races in 2022: Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, and they are all included here. The seventh is New Hampshire, a politically fickle state where Joe Biden performed very well in 2020, carrying the state by seven points after Hillary Clinton carried it by less than half a point four years ago. Its inclusion here is predicated on the Republicans producing a strong challenger for Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-NH) — and they very well may have such a challenger waiting in the wings.

The GOP’s top choice to run against Hassan is almost certainly Gov. Chris Sununu (R-NH), who just easily won a third, two-year term. Sununu considered running against Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) in this past election, but ran for reelection instead; immediately following the election, Sununu’s campaign manager signaled in a tweet directed to Hassan that Sununu may be closer to taking the plunge this time, and a Hassan-Sununu race would be very expensive and closely contested.

Republicans seem likely to take another shot at Sen. Mark Kelly (D-AZ), who will be back on the ballot in search of a full term in 2022, and Republicans may be able to produce a nominee who performs better than outgoing Sen. Martha McSally (R-AZ), who lost in 2018 and 2020. Term-limited Gov. Doug Ducey (R-AZ) would seem to be the leading potential Republican candidate, although there are plenty of other possibilities.

In Nevada, former Gov. Brian Sandoval (R-NV) would be a great potential opponent for Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV), but Sandoval could have run for Senate six years ago and opted not to, and he recently took a job as the president of the University of Nevada-Reno. In all likelihood, Republicans will have to look elsewhere for a challenger to Cortez Masto in an evenly-divided state where Democrats nonetheless appear to retain a narrow statewide organizing edge. In some ways, Nevada is to Republicans what Florida is to Democrats: an elusive and frustrating target.

The three most vulnerable Republican-held seats are in three closely-contested states, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Sens. Richard Burr (R-NC) and Pat Toomey (R-PA) have already announced their retirements. Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) may or may not run again. So these may all be open seats, which would be a change from the 2018 and 2020 cycles, when almost all of the top races on both sides featured incumbents running for reelection.

Current or former House members could be factors in all three races. In the Tar Heel State, outgoing Rep. Mark Walker (R, NC-6) saw his district made much more Democratic in redistricting. He retired but could seek the Senate seat in 2022. Democrats surely would love to see newly-reelected Gov. Roy Cooper (D-NC) run for the Senate, but they may have to look elsewhere — and Democrats ended up striking out in North Carolina this year when their lower-tier nominee, former state Sen. Cal Cunningham (D), blew up his campaign with a late-breaking affair (although Cunningham may very well have lost anyway absent the scandal given Biden’s inability to win the state).

Redistricting in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin could determine whether members such as Reps. Conor Lamb (D, PA-17) or Ron Kind (D, WI-3) would try to make the statewide jump; meanwhile, a couple of Pennsylvania Republicans who retired in advance of 2018, former Reps. Ryan Costello (R, PA-6) and Charlie Dent (R, PA-15), might make sense as the Senate nominee, although if they ran they might have competition to their right in a primary.

Our assumption is that both parties will be able to produce strong candidates in these three races; of the three, North Carolina is the heaviest lift for the Democrats, but with good candidates and a good environment (two big assumptions), Democrats can credibly compete for all three.

Winning two of the three and holding the line elsewhere would get the Democrats a Senate majority even if they lose both Georgia seats in January.

That’s much easier said than done, but it is a credible path, and it may be more achievable than holding the House.

Conclusion

There also may be retirements and newly-open seats that scramble the math. For instance, Sen. Angus King (I-ME) is reportedly a candidate to be director of national intelligence in the Biden administration. Gov. Janet Mills (D-ME) could appoint a Democratic replacement, but that person would have to defend the seat in both 2022 and 2024 (when King’s term expires — he won a second term in 2018). Republicans would surely take a run at the seat if King joined the administration. Biden will have to think long and hard about adding any current senators to his administration given the close balance of power in the chamber. The same can be said about Democratic House members joining the incoming administration. Earlier this week, Rep. Cedric Richmond (D, LA-2) announced he would be joining the administration. Democrats will easily hold the seat in a special election next year, but Democrats can hardly avoid any House vacancies given their reduced majority.

Of course, we know little about the Senate candidates, national environment, and other factors that will determine the outcome of the next cycle. Nor do we even know what the Senate will look like next year, thanks to the Georgia runoffs.

Biden is not guaranteed to suffer down-ballot losses in the House and Senate, even though that is the usual midterm pattern. That Biden does not enjoy big majorities to start his presidency may make it less likely for him to agitate the opposition through the divisive, one-party legislating that helped cost the Democrats and the Republicans the House majority in 2010 and 2018 respectively.

Based on the history, we should presume Republicans will have an edge in the 2022 midterm, but there are no guarantees.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.