HOUSE 2020: INCUMBENTS HARDLY EVER LOSE PRIMARIES

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik

But that doesn’t mean every single one is safe

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

-- Incumbent House members hardly ever lose primaries. In the post-World War II era, more than 98% of House members who have run for reelection have been renominated by their own parties.

-- However, even such a lofty renomination rate suggests that a few House members will lose primaries next year. And the high victory rate for incumbents in primaries doesn’t take into account some members who may have retired in the face of possible primary challenges.

-- There are several incumbent House members who should take seriously the threat of a primary in 2020. As of now, it appears that there is more primary action on the Democratic side than the Republican side.

Incumbent primary threats in 2020

A week before Rep. Joe Crowley decisively lost his primary last year, I tweeted about Crowley’s potential vulnerability, with the caveat that “I have little idea if Rep. Joe Crowley (D, NY-14) is actually seriously threatened by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in his primary next week.” A member of Crowley’s staff sent me an email that quoted this question I raised and said, “He's not. Not at all.”

One couldn’t necessarily blame Crowley and his team for not fully recognizing the threat that Ocasio-Cortez posed. After all, almost all primaries of sitting House members fail.

That history might give some comfort to House members on both sides who have deviated from party orthodoxy and will face primary opposition next year, most notably Rep. Justin Amash (R, MI-3), who now supports impeaching President Donald Trump, and Rep. Dan Lipinski (D, IL-3), whose social conservatism nearly led to his defeat in 2018.

That said, history also suggests that at least a few primary challenges will succeed this cycle. It’s those few examples that will, or at least should, keep House members from taking renomination totally for granted.

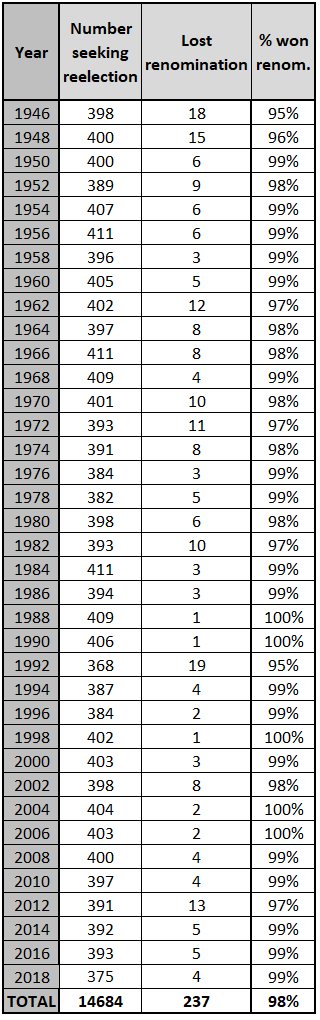

Since the end of World War II, there have been 37 elections for the U.S. House (one every two years). In those 37 elections, an average of 397 House incumbents sought reelection each election year. On average, only six House members failed to secure renomination each election year.

In other words, more than 98% of all House members who have sought renomination in the post-World War II era have received it. Table 1 shows the history from 1946 through 2018.

Table 1: Postwar House renomination rate

Sources: Vital Statistics on Congress, Crystal Ball research

This 98% renomination figure may actually understate the safety of incumbents in primaries, at least in this election. The reason is that 2020 is not a national redistricting cycle. While it is possible that some states will have new maps next year based on a pending Supreme Court decision, the lion's share of states -- if not all of them -- will hold House elections next year under the same maps those states first created following the 2010 census and in advance of the 2012 election. Election years that end in “2” feature new maps across the nation as seats are reapportioned from slower-growth states to faster-growth ones and district lines shift within states in response to the population changes uncovered by the decennial census (this is also typically when one party or the other engages in gerrymandering).

Reapportionment years naturally lead to more primary turnover in the House, as incumbents of the same party sometimes have to run against one another and the power of incumbency can be weakened as an incumbent finds him or herself in a radically-redrawn district. Note that on Table 1, four of the last five House election cycles where the number of incumbent primary losers reached double digits were in years ending with 2; the fifth, 1970, was not a national redistricting year, but the state that then held the nation’s largest congressional delegation, New York, drew new maps that year. One consequence of the new GOP-drawn map was that some white, liberal parts of Manhattan’s Upper West Side were added to a congressional district centered on then-heavily African-American Harlem. That helped Charlie Rangel narrowly defeat then-Rep. Adam Clayton Powell in the Democratic primary, ending the career of one of the most famous House members of the 20th century and beginning the career of another. (Because of his legal problems, the House had refused to seat Powell in 1967, but the Supreme Court later overruled the House, and Powell won reelection in 1968 anyway before losing to Rangel in the 1970 primary). In any event, redistricting can spur a level of primary competition greater than one would otherwise expect in non-redistricting years. But 2020 is not a national redistricting year.

On the other hand, the imposing 98% renomination figure overstates how easy it is for incumbents to be renominated because it doesn’t take into account the members who retire instead of seeking reelection.

For all the ease with which House members are renominated and reelected historically, there actually is a lot of turnover in the House from year to year. As noted above, an average of 397 House members seek reelection every even-numbered year. But the House has 435 members, meaning that on average 38 House districts do not feature an incumbent running for reelection each cycle, which is about 9% of the body’s total membership. So there actually is a fair amount of turnover every two years, if not through incumbents who lose in primaries or general elections, then because of members who decide not to run for the House again for one reason or another.

Some of these members -- not a lot of them, but some -- may have retired at least in part because of fear of a primary challenge. Rangel himself is a recent example -- he barely survived primary challenges from now-Rep. Adriano Espaillat (D, NY-13) in 2012 and 2014 thanks in part to his own personal legal troubles that earned him a censure from the House in 2010 as well as the changing racial composition of his district, which had become increasingly Hispanic over time and through redistricting. Rangel indicated in advance of the 2014 election that he would not run again in 2016, and Espaillat eventually claimed the safely Democratic seat. On the other side of the aisle, former Reps. Marge Roukema (R, NJ-5) and Richard Hanna (R, NY-22) retired, respectively, in 2002 and 2016, which cleared the way for past primary challengers to claim their seats: Those former challengers, who both ran to the right of the more centrist incumbents, would later lose to Democrats.

So the renomination rate for incumbents might be slightly less glowing if some incumbents vulnerable to primary challenge had decided to run again as opposed to retiring and opening up their seats to their past primary rivals.

There’s also the glaring reality that even though there have not been many House primary incumbent defeats in recent years, the ones that have occurred have featured some very prominent members. In 2014, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R, VA-7) lost to Dave Brat; four years later, Crowley, the No. 4 House Democrat, lost to Ocasio-Cortez. Both men might have been speaker if not for their primary defeats: Cantor almost assuredly would have been, perhaps as soon as after the 2014 elections; Crowley may have been sometime in the future. Even though one could count on a single hand the total number of House incumbent primary defeats in each of those years (2014 and 2018), these are the kinds of primary upsets that, with good reason, can spook other incumbent members.

So, who might face the most serious primary opposition? It’s far too early to know for sure, particularly because the seriousness of such challenges often don’t become apparent to outside observers until right before the election. That said, there are some names who stand out on both sides.

Amash, the Libertarian-inclined Republican who holds the Grand Rapids-based seat that is the descendant of the seat once represented by Gerald Ford, made national news recently for concluding after reading the Mueller Report that President Trump should be impeached. Outright opposition to Trump has become harder to assert in the GOP: Disloyalty to the president contributed to a House primary defeat last cycle, that of ex-Rep. Mark Sanford (R, SC-1), although Sanford had preexisting weaknesses stemming from a secret affair he carried on while he was governor. Criticism of Trump almost certainly contributed to Sen. Jeff Flake’s (R-AZ) retirement last cycle, as polling showed him doing very poorly in a primary; the same dynamic may have also helped convince Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN) to retire last cycle, although he was not in as obviously dire of straits as Flake. In any event, Amash -- who has had primary opposition in the past -- will face a challenge again, making him an incumbent to watch in next year’s primary season. Amash could potentially opt against reelection and run for president on the Libertarian Party ticket, which would provide another example of a retiring member leaving the House in advance of what may be a very difficult primary. Three other GOP incumbents, all of whom performed weakly in what should be safe Republican districts last fall, could face trouble within their own party next year if they seek reelection: Reps. Chris Collins (R, NY-27) and Duncan Hunter (R, CA-50), both of whom are under indictment on accusations of corruption, and Rep. Steve King (R, IA-4), whose racist comments and dalliances with white supremacists have aggravated leaders across the political spectrum. GOP leaders have stripped Collins, Hunter, and King of their committee assignments. First-term Rep. Ross Spano (R, FL-15) also could face a primary after admitting to possible campaign finance violations after his victory last November.

Meanwhile, there appear to be more Democrats who already face primary opposition. It may be that Democrats are beginning to experience some of the primary strife that emerged on the Republican side of the aisle during the Obama years. Strangely enough, Trump’s victory, and the mere fact of holding the White House, may have actually had the effect of imposing more primary calm on the GOP side, and Trump’s backing of incumbents can help them fend off challengers if needed (assuming such support is offered). Meanwhile, losing the White House may be contributing to more primary agitation among Democrats, as a leaderless party sorts itself out in the post-Barack Obama era.

Lipinski, the socially conservative Chicagoland Democrat noted above, only barely beat marketing consultant Marie Newman in 2018, and Newman is running again. The brewing primary has already made national news: Rep. Cheri Bustos (D, IL-17), the chairwoman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, was going to hold a fundraiser for her fellow Illinois Democrat, Lipinski, but the optics of the head of the DCCC so openly backing an anti-abortion rights incumbent outraged some Democrats. She recently canceled the event. The DCCC has also caught flak from some Democrats over a policy to freeze out campaign operatives and firms who back primary challengers. Remember: The formal party committees on both sides are first and foremost incumbent-protection organizations; incumbents help fill committee coffers and party groups typically don’t police member ideologies. That said, other ideological groups aligned with Democrats have backed Newman, like EMILY’s List, Planned Parenthood, and NARAL Pro-Choice America. One thing to watch in this race is the number of other candidates who enter: it was just Lipinski versus Newman last time, whereas this time there are other candidates running who could help split the anti-Lipinski vote. The New York Times’ Jonathan Martin reported that Newman and her allies are worried that any extra candidates may effectively be Lipinski plants.

Some other House Democrats who are not particularly liberal, like Reps. Jim Costa (D, CA-16), Stephen Lynch (D, MA-8), and Henry Cuellar (D, TX-28), also seem likely to face primary opposition, although they all start in a much stronger position than Lipinski. (One note: California technically doesn’t have a primary, but rather a top-two system in which all candidates compete on a single first-round ballot and the top-two finishers advance to a general election. Washington has the same system, and Louisiana has a different system in which a candidate can avoid a top-two runoff if he or she wins more than 50% in the first round of voting. Intraparty challenges exist in those states, but they take a different form than in more traditional primary states.)

Any discussion of Democratic primary challenges in the 2020 cycle must include the New York City area, scene of the Ocasio-Cortez insurrection in 2018. While Ocasio-Cortez was the only primary challenger to emerge victorious last cycle, Rep. Yvette Clarke (D, NY-9) nearly lost and Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D, NY-12) was held under 60% of the vote. Shane Goldmacher of the New York Times surveyed the primary scene earlier this year and found that they and many other NYC Democrats could or will face primaries. That includes senior members such as Reps. Jerrold Nadler (D, NY-10), Eliot Engel (D, NY-16), and Gregory Meeks (D, NY-5) as well as newer members like Reps. Tom Suozzi (D, NY-3) and Kathleen Rice (D, NY-4). To the extent that credible primaries develop against some or all of these members, they likely will be fueled by the left, including Justice Democrats, the left-wing group that counts Ocasio-Cortez among its success stories. Ocasio-Cortez herself fundraised off the possibility of facing a primary challenger; it’s possible that two of her first-term allies, Reps. Ilhan Omar (D, MN-5) and Rashida Tlaib (D, MI-13), could be primaried, too. Tlaib in particular merits watching, given that she is a Muslim of Palestinian descent who represents a majority African-American district, and she narrowly won her initial primary victory in 2018 thanks in part to multiple African-American candidates splitting the black vote.

Rep. Diana DeGette (D, CO-1), a long-serving Denver representative, attracted a strong primary opponent, former state House Speaker Crisanta Duran (D), who seemed to be angling for a Senate bid before surprising observers by opting for a safe-seat primary challenge. DeGette fended off a primary challenge by a roughly two-to-one margin in 2018, but Duran may push her harder. Rep. Lacy Clay (D, MO-1) was held under 60% last cycle while Rep. David Scott (D, GA-13) was unopposed, but both will face challenges in majority African-American districts; so too will Rep. Danny Davis (D, IL-7). A couple of long-shot presidential candidates who have been a thorn in the side of House leadership, Reps. Seth Moulton (D, MA-6) and Tulsi Gabbard (D, HI-2), may need to tend to the home fires before too long lest they find themselves in primary trouble. Another, Rep. Eric Swalwell (D, CA-15) might well run again for House if his own bid for the White House doesn’t take off. It is uncertain whether he can clear the Democratic field for his seat, however, since some contenders are already organizing for the contest, although state Sen. Bob Wieckowski (D) has said he would defer to Swalwell if he ends up running for reelection.

Top Democratic leaders in safe blue seats such as House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D, MD-5) and Ways and Means Committee Chairman Richard Neal (D, MA-1) have announced or likely challengers. So too do swing district members like Rep. Tom O’Halleran (D, AZ-1) and Kurt Schrader (D, OR-5), as well as a rising star from a famous family, Rep. Joe Kennedy III (D, MA-4).

This is not intended to be a comprehensive list of all the Democratic and Republican primary challenges, as there are some we may not be mentioning here and more that will emerge over time. And to be clear: Just because a member has a primary challenger does not mean that member is in any trouble. Again, few of these challenges, historically, are successful.

But one never quite knows which challengers will emerge as credible from the much larger group of those that fizzle. The rare incumbents who lose may not comprehend the depth of their troubles until the votes start coming in on Election Night.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.