A Tale of Two Midwestern Gerrymanders: Illinois and Ohio

A Commentary by Kyle Kondik and J. Miles Coleman

|

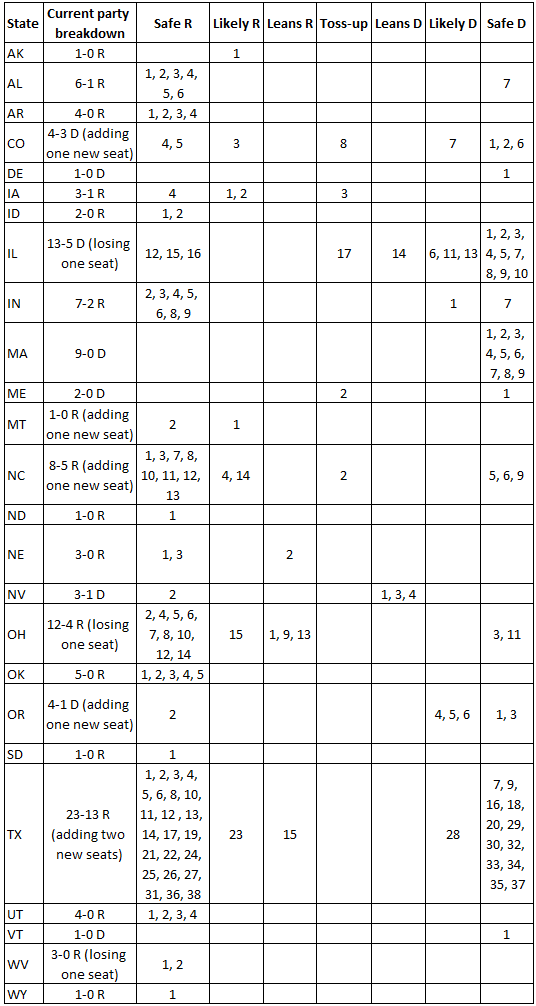

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE-- Gerrymanders by Democrats in Illinois and Republicans in Ohio seek to build upon their dominance of their respective states. -- The Ohio Supreme Court could intervene against the GOP gerrymander there, which perhaps helps explain why Republicans were not as aggressive as they could have been, even though Republicans can reasonably hope that the map they drew will perform for them as intended. -- Massachusetts Democrats and Oklahoma Republicans also recently finalized maps that should allow both to maintain their monopolies on House seats in their respective states. -- Gov. Charlie Baker’s (R-MA) retirement pushes the Massachusetts gubernatorial race from Likely Republican all the way to Likely Democratic. Table 1: Crystal Ball gubernatorial rating change

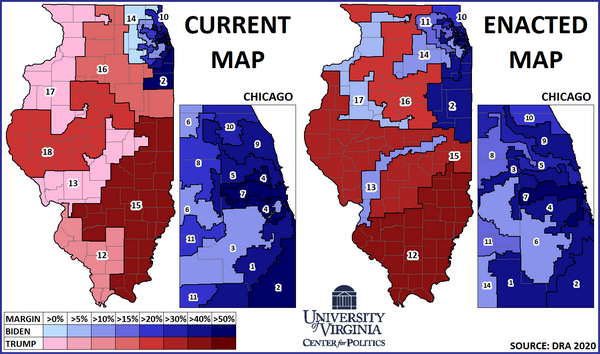

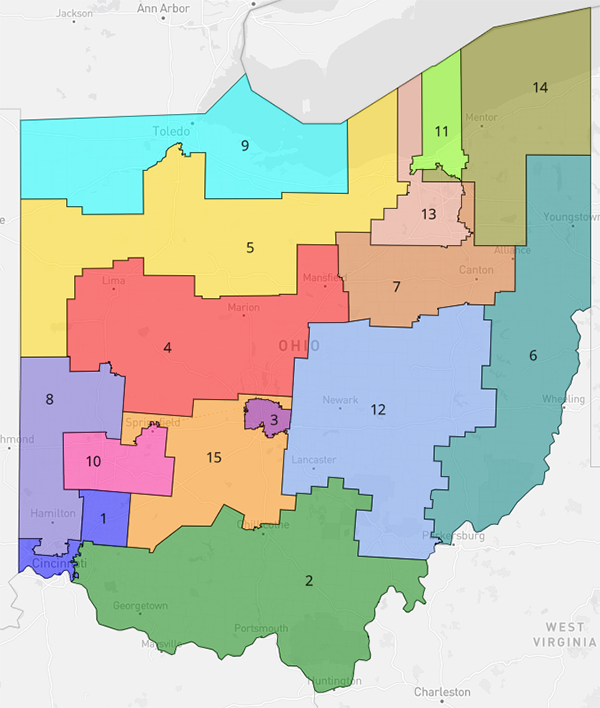

Table 2: Crystal Ball House ratings for states that have completed redistrictingGerrymandering in the MidwestIllinois and Ohio, the 2 most populous states in the Midwest, each used to have reputations as bellwether states. Back in the late 1800s, when national elections often looked like the Civil War (North vs. South), this pair loomed large in part because they had both northern and southern elements. The importance of these states endured throughout much of the 20th century, but Illinois clearly trended Democratic the past few decades as Democratic growth in the dominant Chicagoland area far outpaced Republican gains downstate. Meanwhile, Ohio has become markedly more Republican over the past couple of elections, as growing Republican dominance in outstate areas overwhelmed the Democratic vote in the state’s big city areas. By 2020, both states’ presidential votes were equally distant from the national popular vote: Joe Biden’s margin in Democratic Illinois was 12.5 points better than his national winning margin (Biden won Illinois by 17 as he was winning the popular vote by 4.5 points), while Donald Trump did 12.5 points better in Ohio than he did nationally (Trump carried Ohio by 8 while losing the popular vote by 4.5). The strength of the majority party in each state -- Democrats in Illinois, Republicans in Ohio -- is accentuated in their respective U.S. House delegations. While Biden won 57% of the vote in Illinois, Democrats won 72% (13 of 18) of the state’s U.S. House seats last year. And while Trump won 53% of the vote in Ohio, Republicans won 75% of the state’s House seats (12 of 16). That Illinois Democrats gerrymandered their state while Ohio Republicans gerrymandered theirs helps explain why both parties punched above their weight in House races last cycle, although the Ohio GOP map was more consistently effective: It was designed to elect 12 Republicans and 4 Democrats to the House for the entire decade, and that’s exactly what it did. Meanwhile, Illinois Democrats sought to elect a 13-5 delegation, but that edge was only 10-8 as recently as the 2014 election, and Democrats only maxed out in 2018 by winning a couple of affluent, highly educated Chicagoland seats that they had drawn to be Republican seats at the start of the decade. As we recap the most recent redistricting news, we thought we’d focus primarily on these dueling Midwestern gerrymanders in left-of-center Illinois and right-of-center Ohio, where Govs. J.B. Pritzker (D-IL) and Mike DeWine (R-OH) recently signed into law new maps. ILLINOISTen years ago, when Illinois, with its Democratic trifecta, released its new congressional map, the liberal site Daily Kos Elections dubbed it the start of “Redistmas.” In an otherwise rough redistricting cycle, Illinois was the sole large state that Democrats controlled, and the party made some aggressive choices. Last week, when Gov. Pritzker signed the map that the Democratic legislature produced, it was another “Redistmas” gift to the national party. Map 1 shows the changes. Though the state lost a seat, Democrats created 14 Biden-won seats, up from the current 12. Map 1: Old vs new Illinois districtsThe new map retains 3 heavily Black districts, although they are less so than the previous map. While Rep. Bobby Rush (D, IL-1) keeps a 52% Black Southside Chicago seat, Reps. Robin Kelly (D, IL-2) and Danny Davis (IL-7) see their districts drop to under 50% Black by composition. Though Democratic gerrymandering likely precipitated this, it may have been hard to sustain 3 firmly Black-majority seats anyway -- with the state losing a district, those seats would have had to pick up population in new areas. Perhaps the most notable change in Chicagoland, though, was the creation of a new Hispanic-influence seat. The current IL-4 has its trademark earmuffs shape because it takes in disparate Hispanic communities across the city. At nearly 70% Hispanic by composition, the legislature decided it was appropriate to unpack it to form a new seat. The new IL-4 retains the southern “earmuff,” which has a large ethnically Mexican population, while the northern “earmuff,” which has more Puerto Rican influence, is moved into IL-3 -- the latter also runs west to include pockets of suburban DuPage County. The Hispanic population in the new IL-4 is actually only slightly down from the current version -- perhaps something that speaks to that demographic’s growth in the area -- while 47% of IL-3’s residents are Hispanic. Both seats are overwhelmingly Democratic. Elsewhere in Chicagoland, the creation of the new (and open) 3rd District necessitated the double-bunking of two Democratic incumbents. First-term Rep. Marie Newman, who by some accounts was less-than cooperative with legislative Democrats during the drafting process, is put into IL-6, held by 2-term Rep. Sean Casten. Casten flipped the current IL-6, a Romney-to-Clinton seat, in 2018, while Newman got to Congress by running as a progressive alternative to then-Rep. Dan Lipinski (D, IL-3) in the Democratic primary. IL-6 should be one of the most closely watched member-vs-member primaries of the cycle. From a geographic perspective, just over 40% of the new IL-6 comes from the outgoing IL-3, while Casten only retains a quarter of his current seat -- this arrangement favors Newman, but both members will have a lot of new territory. For the general election, we’re starting this Biden +11 seat as Likely Democratic. On the north side of Chicago, Reps. Mike Quigley (D, IL-5) and Jan Schakowsky (D, IL-9) keep deep blue seats. Biden earned about 70% of the vote in each. Both districts take on more serpentine silhouettes, as they’re strung out further into the suburbs to dilute the GOP vote in other districts. IL-10, which is in the very northeastern corner of the state, was one of the nation’s top House battleground districts a decade ago. But now-Rep. Brad Schneider (D, IL-10) has had this seat locked down for a few cycles and is a heavy favorite. Similarly, though his district is several points less blue than IL-10, we consider Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi (D, IL-8) safe, for now. Krishnamoorthi has amassed a large war chest -- perhaps for an eventual statewide run -- and Republicans left him unchallenged last year in a fundamentally similar district. Going into the redistricting process, Rep. Bill Foster (D, IL-11) had a safely blue seat, while it was clear the legislature would want to shore up Rep. Lauren Underwood (D, IL-14), who was narrowly reelected last year -- in fact, her Trump-to-Biden seat narrowly voted against Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL) last year. Democrats essentially made Foster less secure in exchange for helping Underwood -- and there was a fair amount of territorial swap between their districts. IL-11 keeps its main population centers around Aurora and Naperville, but lurches north to take in red exurban territory from Underwood. In fact, IL-11 now contains a plurality of McHenry County, which is split 4 ways and is the most populous Trump-won county in the state. IL-14 gets more Democratic, but also now contains more of a rural component, as it stretches down to blue collar LaSalle County. IL-11 was a few points more Democratic last year than IL-14, so we'll start the former off as Likely Democratic and the latter as Leans Democratic. While Democratic legislators drew some creative Chicagoland districts, their gerrymandering wasn’t limited to the state’s most populous metro area. The 17th District has been based in the Quad Cities area, near the northwestern edge of the state, since the 1982 election cycle. It has been in Democratic hands for all but a single term (the post-2010 112th Congress) during that span, but the margins have sometimes been narrow, and the area has been open to some statewide Republican candidates. Last year, Rep. Cheri Bustos (D, IL-17), then the chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, had an embarrassingly close call, winning by 4 points, as her constituents narrowly stuck with Trump in the presidential race. Several months before the new maps were even out, Bustos announced her retirement. Though Bustos’s departure sets the stage for a multi-way Democratic primary, the good news for the incumbent party is that the district has become several notches bluer. In short, IL-17 has become more urban: while it relinquishes holdings in a half-dozen rural counties, it takes in more of the cities of Rockford and Peoria, and expands into the blue-trending Bloomington area. With that, Trump’s share drops from 50% in the current district to 45% in the newly-enacted version. Still, while Democrats are undoubtedly better off in the new seat, we’re starting it off as a Toss-up. There is some competition on the Republican side, although their 2020 nominee, Esther Joy King, who took 48% against Bustos last year, is running again and is probably favored to once again win the nomination. Moreover, though the new district takes in a sampling of midsize cities, as the Crystal Ball has discussed before, the overall trend in the “Driftless Area” has been away from Democrats. Republicans likely have more room to grow in the rural quarters of the district, especially if the national environment remains anti-Biden. Moving further downstate, Democratic mappers went on the offensive in the new IL-13. Ten years ago, Democrats drew a map with two marginal St. Louis-area seats: they retained IL-12, which they already held, as a seat that ran from East St. Louis down to the southern tip of the state, and created a new seat, IL-13, which also began near the Missouri border, but extended north to take in the capital, Springfield, and then east to the college town of Urbana. But both districts have elected Republicans since 2014. The Democrats’ solution was to combine the bluest parts of those 2 districts into a single seat. While IL-13 gets, geographically, much thinner, it retains most of its major population centers. IL-13's most notable addition is the city of East St. Louis, which gave Biden 96% of the vote and which it gained from the 12th District. This turned IL-13 from a Trump +2.5 district into one that Biden carried by double-digits. Earlier this week, Rep. Rodney Davis (R, IL-13) announced that he’d seek reelection in the new IL-15, a deeply red seat that wraps around the 13th. While Republicans will have to find a new candidate for the seat, former Pritzker staffer Nikki Budzinski seems to be a clear favorite for the Democratic nomination -- Sen. Durbin, who represented parts of this district in the House before his time in the Senate, recently endorsed her. We are starting IL-13 off as Likely Democratic. In carving out 14 seats intended to elect Democrats, mappers left 3 seats that the Crystal Ball rates as Safe Republican. Before the new map was finalized, Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R, IL-16), one of the most vocally anti-Trump Republicans in Congress, announced his retirement. Though Kinzinger’s home was drawn into Lauren Underwood’s IL-14, he would likely struggle in a Republican primary most anywhere. Kinzinger’s now-vacant IL-16 moves south to include Peoria County, home of Rep. Darin LaHood (R, IL-18). Though his father was known as a moderate Republican -- after his time in Congress, he served as Secretary of Transportation for the first half of Barack Obama’s presidency -- the younger LaHood is a more reliable conservative. IL-16 is the least red of the 3 Republican seat, but it gave Biden just 38%. On the southern extreme of the state, without East St. Louis in his district, Rep. Mike Bost (R, IL-12) gets a considerably safer seat. IL-12 will now contain essentially all of “Little Egypt” -- this ancestrally Democratic region that was home to the late Sen. Paul Simon (D-IL) now gives Republicans crushing majorities. IL-12 gave Trump over 70% of the vote, making it the state’s reddest district. While Davis will run in the reconfigured IL-15, he, or Bost, may have primary competition from first-term Rep. Mary Miller (R, IL-15), who has not announced her plans yet. Miller’s current district was split roughly equally between the 12th and 15th districts, though her home is just inside the former. Unlike Davis, who has had to court swing voters in a light red seat over the past decade, Miller has spent her term as an unapologetic Trump Republican -- something that could make her better-positioned to win a primary in the 15th. Alternatively, Miller could simply opt to retire. So while Democrats will have to work to keep some of the Biden-won districts in their column next year, they are favored in 13 of the districts and could win a 14th, IL-17, while Republicans will need a large-scale wave to match or exceed the 5 seats they currently hold. OHIOThe new Ohio map is definitely a Republican gerrymander, but it is not a maximal Republican gerrymander. However, there are good reasons to believe that it will function as though it is a maximal Republican gerrymander -- if the Ohio Supreme Court does not force changes to it. In 2018, Ohio voters overwhelmingly approved a state constitutional amendment that, among other things, sought to promote compromise in order for the state to create maps that would last for 10 years, the customary shelf life of district maps. Failing that, the majority party could pass a map for 4 years (or just 2 elections) without minority party support, but there are certain state constitutional stipulations about splitting counties and not unduly favoring one party or the other that hypothetically constrains the party in power’s ability to gerrymander. This is why the Ohio Supreme Court, where Republican justices hold a 4-3 edge, is an important wild card in this process (Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor, a Republican, could potentially side with the 3 Democratic justices and force changes to the new map). But for now, let’s assume that the new map is in place for 2022. Even though some of the districts are competitive on paper, Republicans can reasonably hope that it will produce their intended result -- a 13-2 Republican advantage, up from 12-4 on the current map. Map 2 shows the new map, courtesy of Dave’s Redistricting App. Map 2: New Ohio congressional mapAccording to DRA, districts 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, and 14 all gave Donald Trump at least 55% of the vote in 2020. All of them are Safe Republican. Declining Democratic fortunes in some of their former strongholds, like Lorain County (just west of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga County) and Mahoning and Trumbull counties (home of postindustrial Youngstown and Warren, respectively), made it easy for GOP mapmakers to attach these counties to redder areas. Both Lorain and Mahoning voted for Donald Trump in 2020 after Hillary Clinton carried them in 2016 with margins that were much-reduced from previous Democratic performance. Lorain County is now in OH-5, which sprawls all the way to the Indiana border, while Trumbull and Mahoning now make up the northern portion of eastern Ohio’s OH-6. Additionally, OH-10 in the Dayton area is also Safe Republican: It voted for Trump by a modest 4-point margin, but Rep. Mike Turner (R) has easily held the seat for a couple of decades, even in good Democratic years. Turner is sometimes mentioned as a possible Senate candidate, but the hour is growing late for him to enter and there are several high-profile contenders already running. Still, another Republican would likely hold this seat anyway. The 15th District, which now-Rep. Mike Carey (R) just won in a special election, becomes more competitive in this map as it takes in more of Democratic Franklin County (Columbus), but it still went for Trump by 6 points. It’s Likely Republican to start. Democrats have just 2 Safe seats, the overwhelmingly Democratic OH-11 in Cleveland and OH-3 in Columbus. Joe Biden won more than 70% of the vote in each. That leaves 3 swing seats: OH-13 in the Cleveland/Akron area and OH-1 in the Cincinnati area, both of which voted narrowly for Joe Biden, and OH-9 in Northwest Ohio, which voted for Trump by about 4.5 points. OH-13 has no incumbent -- retiring Rep. Anthony Gonzalez (R, OH-16) could have run here had he sought reelection -- while veteran Reps. Steve Chabot (R, OH-1) and Marcy Kaptur (D, OH-9) are the incumbents in, respectively, the Cincinnati and Toledo-based seats. We say that this is “definitely” a Republican gerrymander because of the choices made by the Republicans who drew the map, particularly in the Cincinnati and Toledo seats. For instance, while Joe Biden won the new OH-1 in the Cincinnati area by a couple of points, the district connects heavily Democratic Cincinnati (which cannot be split between districts based on the voter-approved 2018 constitutional amendment) with deeply Republican Warren County in the Cincinnati suburbs. Instead of splitting Hamilton County (Cincinnati) 3 ways, as this map does, a non-gerrymandered map could keep Hamilton County, which voted for Biden by 16 points, mostly whole -- the county has about 830,000 residents, or about 45,000 more people than the ideal population size for 1 of Ohio’s 15 districts. But that would give Democrats a third safe-ish seat, in addition to the deeply Democratic enclaves in Columbus and Cleveland. So Republicans drew OH-1 as a competitive seat that they can be reasonably confident Chabot can hold. Likewise, a more compactly-drawn version of OH-9 would have made the Toledo-area seat into more of a true swing seat. Notice how the district is shaped like the bottom half of a dumbbell, with Toledo’s Lucas County connecting geographically larger areas to both its west and east. Conveniently for Republicans, this construction draws out much of competitive Wood County (directly to Toledo’s south) and its county seat, the college town of Bowling Green. Adding the rest of Wood County and removing some of the blood red Republican counties to the west of Toledo would make this a more marginal seat, although it is still winnable for Kaptur, who has represented versions of this district since her first election in 1982. Still, only 7 Democrats were elected in Trump-won seats in 2020, so we think Kaptur would be in for a significant challenge in the context of a 2022 midterm environment. That electoral context is vital to understand what’s going on with this map. Remember: Even if it’s upheld by the Ohio Supreme Court, the map would only be in place for the 2022 and 2024 elections. In other words, this map only has to perform as intended for Republicans in 2022 -- a midterm election held under a Democratic president who, at least at the moment, is unpopular -- and 2024 -- a presidential election year in which the Republican presidential nominee has a good chance to win Ohio with a solid margin given recent trends in the state. So questions about how the map might perform, for instance, in a 2026 midterm with an unpopular Republican president in the White House, or how demographic and political changes might alter the map over the course of the decade -- things that gerrymanderers in other states need to take into account, under the assumption that their handiwork will need to hold up over the course of 5 elections instead of only the next 2 -- don’t apply here. We’re starting the 3 most competitive seats -- Chabot’s OH-1, Kaptur’s OH-9, and the open OH-13 -- as Leans Republican. These seats are all winnable for Democrats, but the way they were drawn combined with the likely political environment next year means we see a Republican edge to start. Again, the Ohio Supreme Court will weigh in here at some point and determine whether the Republicans went too far based on the new rules. Ohio Republicans can argue that they could have been more aggressive but were not, which they absolutely could have been -- earlier proposals from the state House and Senate show how that could have worked. But Republicans can also be reasonably confident that they’ll get the outcomes they want next year and in 2024 -- and then they can draw a new gerrymander in 2025. Democrats will hope the court forces changes: most obviously, pushing for a redraw of OH-1 so that it becomes more Democratic, which would be easy to do. So we’ll just have to wait and see. There are 3 other states we wanted to briefly address in this week’s update: Wisconsin, which does not have a map in place yet, and Oklahoma and Massachusetts, which recently finalized their maps. WISCONSINWhile we’re discussing the Midwest, we wanted to offer a quick word on Wisconsin. Earlier this week, in a win for Republicans, the state’s conservative-majority state Supreme Court indicated that it favored a minimal change approach. It always seemed unlikely that Gov. Tony Evers (D-WI) and the heavily Republican legislature would agree on a plan, so court action looked inevitable. But this likely means that the existing Republican gerrymander will serve as a template for the new House map. The current 8-seat map features 6-Trump won seats, with Democrats holding safe seats based in Milwaukee and Madison. Though a least change approach could theoretically make it harder for Republicans to move WI-3, an open Obama-to-Trump Democratic seat in western Wisconsin, much to the right, it will likely remain a top Republican pickup opportunity. Rep. Ron Kind (D, WI-3) is retiring. So the court’s approach makes a 6-2 Republican delegation a bit more likely. OKLAHOMAOklahoma, one of the reddest states in the country, has a 5-0 GOP congressional delegation. With its number of districts staying the same, and Republicans in total control of the process, the prognosis always seemed be an outcome that preserved the status quo. The biggest goal of state Republican mappers was to shore up first-term Rep. Stephanie Bice (R, OK-5), who won a close contest last year against then-Democratic Rep. Kendra Horn, one of 2018’s surprise winners. For the past few decades, OK-5 has been an Oklahoma City district, although the version that was in place last year had two rural counties. The new version of the district loses some urban precincts but expands to include all of rural Lincoln County -- which Trump carried by over 60 points -- as well as chunks of two other nearby red-leaning counties. These changes push OK-5 from a single-digit Trump seat to one that the former president would have carried by 18 points. Though that margin is still more than 10 percentage points worse than Mitt Romney’s 2012 showing in the district, it is enough to move OK-5 off the competitive board. None of the 4 other districts would have been within 20 points in last year’s presidential contest. Aside from OK-5, the next most competitive district is the Tulsa-based OK-1. Though Biden was the first Democratic nominee to crack 40% of the vote in Tulsa County since 1964, the district also includes even redder selections of a few adjacent counties. All 5 districts are Safe Republican. MASSACHUSETTSMassachusetts, with 9 Democratic-held districts, has the largest single-party delegation in the House. With a largely minimal change plan passing last week -- one that Gov. Charlie Baker (R-MA), somewhat surprisingly, signed -- the Bay State seems likely to keep that designation for the next Congress. Compared to the outgoing plan, some of the most substantial changes were made with incumbent preferences in mind. Last year, House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Richard Neal (D, MA-1) beat back a primary challenge from then-Holyoke Mayor Alex Morse to secure renomination in his western seat. Not surprisingly, about a dozen towns that Morse carried were removed from MA-1. Similarly, in 2018, Rep. Lori Trahan (D, MA-3) won her seat by earning a 22% plurality in a 10-way primary. Andover, the home of second-place finisher Daniel Koh, was transferred out of the district. Republicans have been locked out of the Massachusetts delegation since the 1996 election cycle. They have occasionally been somewhat competitive: most recently, they held Rep. Bill Keating’s (D, MA-9) margin to just under 10 percentage points in the GOP wave year of 2014. As we summed up in our redistricting preview series, if any of their Massachusetts seats are in jeopardy, House Democrats are likely in for a world of hurt next year. All 9 districts are Safe Democratic. P.S. Massachusetts gubernatorial rating changeFinally, we wanted to address Gov. Baker’s decision not to seek reelection, which he announced on Wednesday. Despite the dark blue lean of his state, the moderate Republican has routinely ranked among the nation’s most popular governors since he first took office in 2015. Though Baker’s stances against former President Trump played well with the Bay State electorate as a whole, his standing among voters in his own party is not good. Because Massachusetts has open primaries, it seemed Baker was always going to be reliant on independent voters pulling ballots for him in a Republican primary, especially if he received a high-profile conservative challenger. In July, such a candidate materialized: former state Rep. Geoff Diehl, who was active in Trump’s campaign and recently got the former president’s endorsement. In 2018, Republicans nominated Diehl against Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) -- he lost by 24 points. With Lt. Gov. Karyn Polito -- Republicans’ best non-Baker option -- also not running, Diehl appears to be the favorite for the GOP nomination. On the Democratic side, state Attorney General Maura Healey is a possible top contender, although other Democrats are already running and more could jump in. Marty Walsh, the current Labor Secretary who was formerly Boston’s mayor, is reportedly weighing a run. Had Baker stood for, and won, renomination, this would be a Safe Republican contest. We’ve kept the race as Likely Republican, to reflect that, though he’d be favorite, it was unclear if he’d actually run again. With this news, we’re shifting our rating all the way to Likely Democratic under the working assumption that the Republican nominee will possess far less crossover appeal than Baker and that the Democratic nominee will be relatively strong. See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik. See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman. See Other Political Commentary. Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate. |

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.