2018 Senate: The Democrats Are Very Exposed

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik and Geoffrey Skelley

But potentially counteracting forces -- partisan polarization & the negative midterm effect on the president’s party -- complicate the midterm picture

A potential silver lining for Democrats is that they head into the 2018 midterm as the party that does not hold the White House, and the “out” party typically makes gains down the ballot in midterms. But it will be difficult for Democrats to make Senate gains in 2018: Despite being in the minority, they face a near-historic level of exposure in the group of Senate seats being contested in two years, Senate Class 1.

It’s hard to overstate how disappointing 2016 was for Democrats in the Senate. Yes, the party did net an extra two seats by defeating Republican incumbents in Illinois and New Hampshire despite Hillary Clinton losing her bid for the presidency, so the next Senate will be 52-48 Republican. But given that for most of the cycle it looked like Clinton would win the White House and also deliver the Senate, the Democrats clearly did not realize their potential this year.

One of the big reasons why the Senate majority appeared in reach for the Democrats in 2016 was that the Republicans were, and still are, overexposed in Senate Class 3, the 34 seats that were up for election this past November. Republicans controlled 24 of 34 seats on a map where they had made substantial gains the last two times it had been contested, the GOP wave year of 2010 (when the Republicans gained six seats) and President George W. Bush’s reelection in 2004 (when they gained four). But the GOP largely held the line and now hold a 22-12 advantage in this Senate class, which won’t be up for election again until 2022, which could be President Donald Trump’s second midterm election (although that’s of course a very long way off).

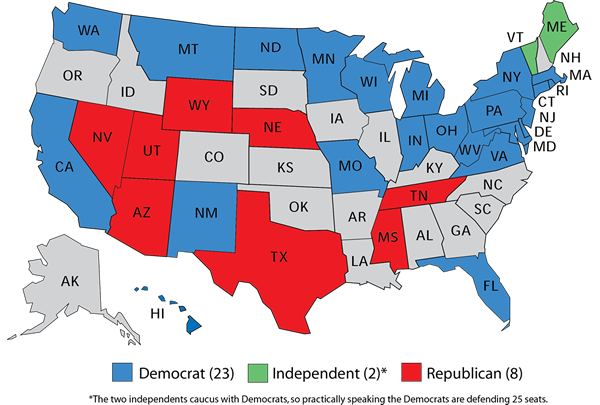

Always looming over 2016, though, was the 2018 map. Including the two independents who caucus with the Democrats, the party holds 25 of the Class I Senate seats that are up for election in 2018, while the Republicans hold only eight. Again, a look back at the last few times this group of seats was contested explains the Democrats’ exposure. After Republicans netted eight seats on this map in the 1994 Republican Revolution (and party switches by Sens. Richard Shelby of Alabama and Ben Nighthorse Campbell of Colorado from Democrat to Republican would essentially make it 10 by the time of Campbell’s switch in March 1995), Democrats made big gains in Class 1 in both 2000 (four) and 2006 (six). Going into 2012, it appeared that Democrats would lose seats, but they upset expectations and instead gained two, which is why they are so overextended now.

Map 1: Senate seats up in 2018 midterm election (Senate Class 1)

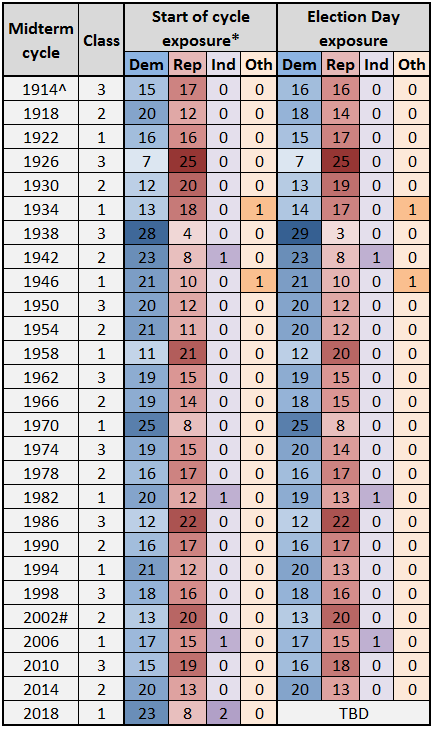

Only three times before in the era of popularly-elected senators has a party begun a midterm cycle as exposed as the Democrats are in 2018, and only once since World War II. When we say “begun,” we mean the partisan makeup of the class up for election in December about two years prior to Election Day — where we are in the calendar right now.[*]

In December 1924, Republicans held 25 seats that were up in the 1926 midterm election, and that party makeup remained the same up to Election Day. In November 1926, the GOP lost six of the regularly-scheduled contests, as well as a concurrent special election in Massachusetts, with the Democrats defeating seven Republican incumbents (including an appointed one in the Bay State) to make their gains. The Democrats’ success in 1926 would eventually play a part in the record-high exposure for a party in any Senate cycle: In 1938, Democrats had to defend nearly 30 seats, the result of the party’s banner 1926 and 1932 cycles (they gained 11 total net seats in the latter). Following the appointment of a Democrat to fill a vacancy in a formerly GOP-held seat in South Dakota on Dec. 29, 1936, Democrats held 28 seats that were up in the 1938 midterm election. By the time Election Day 1938 rolled around, they were also defending a seat in Oregon, putting them at 29 seats out of the 32 that were regularly up. (Remember, this was before Alaska and Hawaii joined the Union, thus there were 96 senators and 32 in each of the Senate’s three classes.) The outcome was a Republican net gain of eight seats, with Democrats losing seven of the regularly-scheduled seats they held, as well as a concurrent special election in New Jersey. Five Democratic incumbents fell by the wayside in the 1938 general election. Republicans also picked up 81 seats in the House in their 1938 wave, a midterm shellacking that some argue effectively ended President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

The last time a party was as exposed as Democrats are in 2018 was in the 1970 cycle. At the end of 1968, 25 Democratic-held seats were up in the 1970 midterm. There are some similarities between the position of Democrats in 1970 and 2018. First, Class I Senate seats were up in 1970, just as they are in 2018. Second, a sizable number of Democratic-held 1970 Senate seats (13) were up in states that Republican Richard Nixon had just carried in the closely-contested 1968 presidential election, compared to the 10 Democrats are defending in 2018 in Trump states. Perhaps endangered Democrats up in 2018 can feel a little bolstered by the fact that Democrats only lost three net seats in the 1970 midterm despite having to defend numerous seats, many in states that backed the most recent GOP presidential nominee. Overall, 11 of the 12 Democratic incumbents running in states won by Nixon in 1968 won reelection in 1970 (though Harry Byrd Jr. of Virginia ran as an independent that cycle, eschewing his previous party label).

Democrats overcame their overextension in 1970 in part because Nixon held the presidency, while the overextended parties in 1926 and 1938 held the White House, perhaps contributing to their bigger losses. So as the Democrats assess their Senate odds in 2018, they can take some solace in the possibility that the midterm dynamic might help them protect their many vulnerable incumbents.

Table 1: U.S. Senate party exposure in midterm elections, at start of cycle and on Election Day

Notes: *“Start of cycle exposure” refers to the partisan makeup of the Senate class in question as of the December two years prior to Election Day (e.g. December 2016 for the midterm cycle 2018). ^The “start of cycle exposure” for 1914 began a few months before the ratification of the 17th Amendment, which established the popular election of U.S. senators, so 1914 data are based on the partisan makeup of Senate Class 3 as of the start of the 63rd Congress on March 4, 1913 rather than December 1912. #The appointment of Sen. Dean Barkley (I-MN) on Nov. 4, 2002 (the day before Election Day) to replace Sen. Paul Wellstone (D-MN), who died in the midst of his reelection campaign on Oct. 25, 2002, is not included. Changes in party exposure from the start of a cycle to Election Day reflect partisan changes due to vacancies and ensuing appointments and/or special elections, party switches, the addition of new states to the Union, etc.

Source: Crystal Ball research.

But comparisons between 1970 and 2018 should be made with caution. First, the political environment was far less polarized in 1970 than it is now. Take, for instance, the fact that about half of the states that held Senate races in the 1968 and 1972 presidential cycles had split presidential-Senate outcomes, the latter being Nixon’s “lonely landslide” win against George McGovern. Compare that to 2016, which saw 100% of states with Senate races vote straight-ticket for president and Senate (with Louisiana’s final outcome still to be determined in a runoff this Saturday). Granted, 2018 is a midterm year, but the point is that the high level of party polarization matters. In 2014, Republicans won all seven of the Senate contests that took place in states won by Mitt Romney in 2012. For Democrats in 2018, they only have one scheduled (i.e. Class I) target in a state won by Hillary Clinton — Sen. Dean Heller (R-NV), who may opt to run for governor instead — and only one other battleground state Senate seat to compete for — Arizona, where Sen. Jeff Flake (R-AZ) may face a notable primary challenge from Kelli Ward (R), a former state senator who lost to Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) in the GOP primary for Arizona’s other U.S. Senate seat in 2016.

Thus the 2018 midterm cycle features a clash of two patterns in American politics. On the one hand, the president’s party almost always suffers to some extent in midterm elections, though more consistently in the more-nationalized elections for the U.S. House than in the more-parochial elections for the U.S. Senate.

On the other hand, in this polarized era of American politics, the fact that Democrats are defending seats in some very Republican states suggests that the GOP should be in a good position to pick up seats despite the midterm environment.

[*] It’s hard to say how seriously they are under consideration, but Sens. Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND) and Joe Manchin (D-WV) both have been mentioned as possible Cabinet appointees in the incoming Trump Administration. If Heitkamp left her seat, North Dakota would hold a special election within 95 days of the vacancy, and we can only assume Republicans would be heavily favored (Trump won the state by nearly 36 points). If Manchin left his seat, incoming Gov. Jim Justice (D-WV) would presumably appoint a Democrat to replace him, but appointed senators often don’t have much of an advantage if they run for reelection, and Manchin may be the only Democrat capable of holding a Senate seat in the reddening Mountain State (Trump won it by almost 42 points, the biggest presidential margin of victory in the state’s history).

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

Geoffrey Skelley is the Associate Editor at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary by Geoffrey Skelley.

See Other Political Commentary.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.