Virginia and New Jersey Governors 2021: A First Look

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman

In blue states, Democrats could match milestones and break curses.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Virginia Democrats are trying to win three consecutive gubernatorial races, a feat the party has not accomplished since the 1980s.

— Former Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D-VA) is the favorite for his state’s Democratic nomination, though he faces a diverse field.

— In a move that’s ruffled some feathers on their side, Virginia Republicans will select their nominee at a May convention.

— In New Jersey, Gov. Phil Murphy (D-NJ) is poised to become the state’s first Democratic governor to secure reelection since 1977.

— Virginia’s open-seat race starts as Leans Democratic in the Crystal Ball ratings. New Jersey starts as Likely Democratic.

Back to the 1980s for Virginia Democrats?

With the presidential contest over, and the midterms almost two years off, Virginia and New Jersey are both due for some attention. As the only two states that hold their gubernatorial elections in the odd-numbered years after presidential elections, their results are sometimes framed as barometers for national political moods.

We’ll start with the Center for Politics’ home of Virginia, but before we dive into the current election year, some historical perspective is in order.

Though they’ll settle on their nominee in a June primary, the ultimate goal of Virginia Democrats in 2021 will be to accomplish something they haven’t done since the 1980s: win three consecutive gubernatorial elections.

During the closing decades of the 20th century, and into the first decade of the new millennium, Virginia was the ultimate contrarian state, at least in state contests. Starting in 1977, the Old Dominion elected governors from the political party opposite that of the previous year’s presidential winner — this streak would continue until 2013, as now-former Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D-VA) won despite President Barack Obama’s reelection the year before.

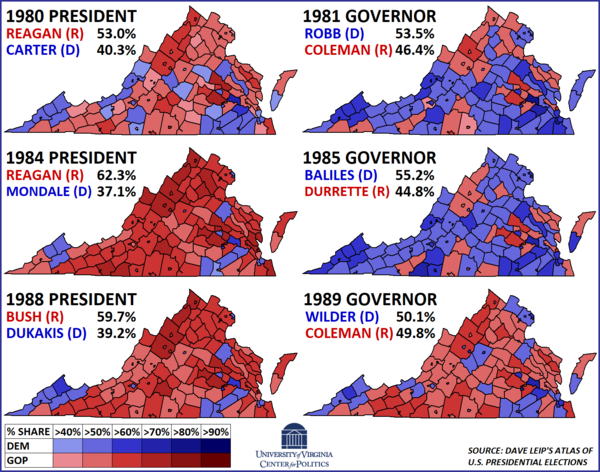

While the electoral pattern that dominated that stretch of the state’s history makes for something of a fun political trivia point, Virginians didn’t simply go down that path just for the sake of voting against the White House. Zeroing in on the 1980s, Frank Atkinson, in his book Virginia in the Vanguard, identifies several reasons why state Democrats found success during that decade. Though Virginia — and the country as a whole — gave GOP presidential nominees easy wins in 1980, 1984, and 1988, Democrats cobbled together a string of victories in the 1981, 1985, and 1989 gubernatorial contests (Map 1).

Map 1: Virginia presidential and gubernatorial races in the 1980s

From 1969 to 1977, Virginia Republicans also won a gauntlet of three gubernatorial races, so the pro-Democratic trend that began in 1981 represented a dramatic sea change in state politics.

What caused the tide to shift? Atkinson points out that, broadly, Democrats enjoyed something of a best-of-both-worlds posture. Once in power, their governors took credit for the economic gains of the Reagan and Bush years. While bashing the national Republican administrations on the campaign trail, Virginia Democrats invested new revenue in popular programs, like infrastructure and education — this, of course, helped them when voters went to the polls.

Quality, and in some cases, history-making, candidates also bolstered Democratic prospects in the 1980s. Elected in 1981, Gov. Chuck Robb (D-VA) was the face of the state party that decade. Robb framed himself as a pragmatic moderate, but liberals could appreciate his connection to Lyndon Johnson (he is the late president’s son-in-law). In 1985, then-state Attorney General Gerald Baliles won the governorship by running very much in the same mold, with an emphasis on the bread-and-butter Democratic issues of transportation and education.

Baliles, though a white candidate himself with a moderate veneer, led what Atkinson dubbed a “rainbow” ticket. Democrats nominated state Sen. L. Douglas Wilder for lieutenant governor, who would become the first Black candidate elected statewide, and state Delegate Mary Sue Terry for attorney general, who became the first woman elected to a statewide office. In 1989, Wilder again made history: his narrow gubernatorial victory marked the first time a Black candidate was popularly elected to lead *any* state — a distinction that Virginia’s complicated history on race made even more significant.

A third advantage Democrats had in the 1980s was fractious opposition. If Virginia Democrats fielded tickets that successfully appealed to both white moderates and minorities, state Republicans seemed to have something of an identity crisis. The state GOP of the time proved to be a wobbly coalition of religious conservatives, Appalachian moderates, and former Byrd Machine loyalists — among other groups. In the 1985 and 1989 contests, Republicans also seemed to struggle with messaging; given the historic nature of Wilder’s candidacies, attacks on him that were perceived as too racially tinged risked backfiring.

Though Virginia Republicans had much better luck in the 1990s, the party finds itself again struggling for relevance. After victories in 2013 and 2017, Virginia Democrats are positioned to pull off another electoral hat trick. If they accomplish that this year, it will probably have more to do with the state’s partisanship more than anything else. President Joe Biden’s 54%-44% showing in the state in 2020 was the best margin for a post-World War II Democratic presidential nominee. More tellingly, Republicans have lost all 13 statewide races that Virginia has seen since 2012 — even during the 1980s, the GOP at least claimed the state’s electoral votes and held both its Senate seats for much of the decade.

With that history in mind, let’s consider the current field.

The Democrats: McAuliffe vs. the field

For much of 2020, one of the worst-kept secrets in Virginia politics was that former Gov. Terry McAuliffe was eyeing a comeback. A Democrat with strong ties to the Clintons, he won what turned out to be a very competitive 2013 gubernatorial contest. As governor, McAuliffe sported generally positive approval ratings — as he was leaving office in late 2017, polling from Quinnipiac University put his approval rating at a healthy 56%-36% spread. It’s likely McAuliffe would have been reelected in 2017, but Virginia is the only state in the Union that limits its governors to serving a single consecutive term. Though McAuliffe wasn’t on the ballot himself, his popularity certainly didn’t hurt his party that year — he campaigned for now-Gov. Ralph Northam (D-VA) in 2017, and the Democratic ticket swept all three of the state’s top offices for the second straight cycle.

In December 2020, McAuliffe formally announced that he’d run again. If Virginia Democrats, as a whole, are looking for a return to the 1980s, McAuliffe, personally, may have the 1970s in mind. In the 1973 gubernatorial contest, then-former Gov. Mills Godwin (R-VA) staged a return to the governor’s mansion — he previously occupied it, as a Democrat, for a term after the 1965 election. Godwin is the most recent Virginia governor to serve two non-consecutive terms, though Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA), who is also a former governor, was considered a potential 2013 candidate before ruling out a return.

A former chair of the Democratic National Committee, McAuliffe entered the race with a known fundraising advantage. Despite a relatively late entrance into the race — most of his rivals got in months earlier — as of January, the former governor had a war chest of about $6 million, more than the rest of the primary field combined. As the only candidate who’s experienced the state’s top job, his campaign seems to be betting that, in a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has upended society, voters will see him as a steady hand.

Few doubt McAuliffe’s commitment to the Democratic Party — during his term, he constantly promoted Virginia on the national and international stages, but often battled a hostile GOP legislature at home. Still, his competitors argue that the party’s nominee should be more in touch with current political realities. McAuliffe was first on the state ballot in 2009, when he unsuccessfully sought the gubernatorial nomination. The party’s electorate has changed markedly over the past dozen years, and the state overall has moved more firmly into the Democratic column.

While Virginia’s politics will likely be more prominent in national news this year, the race for the governorship truly began almost a year ago. In May 2020, state Delegate Jennifer Carroll Foy was the first Democrat to announce a gubernatorial run. Elected in 2017, Carroll Foy has a background as a public defender and has stressed issues of criminal justice — she’s often discussed her support for cash bail reform. After Democrats took control of the legislature in 2019, she was instrumental in the state’s efforts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment. She resigned from the state legislature to focus on her run.

In June 2020, state Sen. Jennifer McClellan entered the Democratic primary. Almost immediately, some parallels to Carroll Foy sprung up: both offer a generational contrast to recent governors — on Election Day, they’ll each be in their 40s — and either would be the first Black woman elected governor of any state. McClellan, though, has more experience in government and cited quality public education as her highest priority.

From a purely geographic perspective, McClellan has an advantage. While her four opponents come from Northern Virginia — a region that the party has increasingly leaned on in general elections — she represents a Richmond-area district. In fact, occupants of McClellan’s seat tend to go on to bigger things: her immediate predecessor is now-Rep. Donald McEachin (D, VA-4), who won a newly-drawn congressional seat in 2016, and former Gov. Doug Wilder represented it for several terms before launching his statewide career. As the state Senate is only up in odd-numbered years before presidential elections, McClellan can at least keep her seat if she comes up short in the gubernatorial primary.

A fourth primary candidate — who’s also Black and in his 40s — is Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax (D-VA). When Fairfax succeeded now-Gov. Ralph Northam as lieutenant governor, he was seen as a rising star in the party. However, in early 2019, around the time Northam was fighting for his political life after some of his medical school yearbook pictures came to light, Fairfax was battling a scandal of his own, as two women accused him of sexual assault. Northam simply rode out his yearbook scandal and worked to make amends but Fairfax’s reputation never recovered. As a result, even as a sitting statewide officer, Fairfax has generally not been a factor in the race — with only $79,000 in the bank, as of January, he lacks any major endorsements.

The final Democratic candidate, who entered in January, is state Delegate Lee Carter. Like Carroll Foy, he was initially elected to a Northern Virginia district in 2017. A member of the Democratic Socialists of America, Carter co-chaired Sen. Bernie Sanders’ (I-VT) 2020 primary campaign in the state. Though Virginia, to put it mildly, is not a state that has historically been defined by a progressive political culture, Carter is angling for the support of blue-collar voters. In the legislature, he’s positioned himself as a friend of labor — recently, he introduced a bill that would shield teachers from being fired during strikes. Still, unions have not rushed to endorse Carter, and he is far behind in fundraising.

The bottom line for the Democratic race is that the well-funded McAuliffe appears to have a significant edge. As Virginia doesn’t have runoffs, he could simply win with a plurality in a divided field. The filing deadline is in late March — if some candidates drop out before then, or don’t get around to actually filing, McAuliffe would likely have a harder time if his opposition is more consolidated. Either way, we’ll have to see if any of his declared rivals pick up steam leading into the June 8 primary.

With a convention, GOP tries to avoid chasing away swing voters

If the Democratic primary for Virginia governor seems straightforward, the Republican side is looking more volatile. To start, while the Democratic race currently features only five candidates, nine Republicans are running, though only a few have a serious chance of being nominated. Second, the party will choose a nominee at a May drive-through convention. In February, after a process that was marred by indecision, party officials announced the evangelical Liberty University, in Lynchburg, as its convention venue. This decision caught some university personnel flat-footed, though it apparently won’t be held on the actual university campus (the formal details are still being worked out).

For Virginia political observers, especially those in the Charlottesville area, the convention storyline may bring back memories of last year’s congressional race. Now-Rep. Bob Good (R, VA-5) ousted former Rep. Denver Riggleman (R, VA-5) at an opaque, drive-through convention that was held in Campbell County, just east of Lynchburg.

The convention format may have the effect of hampering state Sen. Amanda Chase’s prospects. She fashions herself as “Trump in heels,” and has been at war with the party establishment for much of the last year. When it was first reported that the state party was considering a convention, Chase threatened to leave the party and run as an independent, though she eventually settled on seeking the GOP nomination anyway. Still, as recently as last week, she seemed to be singing her old tune: as she accused the state party committee of stacking the upcoming convention, Chase suggested that a new political party is needed.

Traditionally, state Republicans have preferred conventions, which are decided by a relative handful of party loyalists, to primaries — as Virginia has no party registration, primaries are essentially open to any registered voter. From 1953 to 1985, the Republicans nominated gubernatorial candidates via convention, and they’ve only since held primaries in 1989, 2005, and 2017.

Put in a historical context, Chase’s opposition to a convention is a curiosity. In recent decades, state conventions typically benefited the more ideological candidates — in other words, those that could inspire partisans to show up for hours at a time. In last year’s VA-5 race, Good, running as a “Biblical conservative,” benefited from that format against Riggleman, who was a Republican with libertarian leanings. As an aside, after his losing his seat, Riggleman seemed open a 2021 gubernatorial bid. Given his recent criticisms of the GOP, he may consider running as an independent — in that case, he’d have until August to file papers for his candidacy. Before his time in Congress, he was briefly a candidate for governor in the 2017 Republican primary.

In 2013, the last time Republicans held a gubernatorial convention, then-Lt. Gov. Bill Bolling, a well-known moderate who’d have some appeal to Democrats in a general election, was muscled out by then-state Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli, a strident conservative with a reputation as an immigration hawk. Had the contest been decided in a primary, Cuccinelli may have struggled to expand past his base. But post-Trump, a different dynamic may be at play in state primaries. It’s easy to see how Chase could turn out low-propensity voters who are sympathetic to Trumpism, but are suspicious of political parties and wouldn’t participate in a convention.

At the 2021 convention, Republican delegates will cast ballots in Lynchburg, with their preferences ranked. The Chase campaign worries that this system will benefit candidates who have deeper connections to the state party. Specifically, Delegate Kirk Cox, who served as Speaker of the state House from 2018 to 2020, would seem to have the inside track in that scenario. Cox was first elected to the House of Delegates in 1989, and has the most endorsements — notably, former Gov. Bob McDonnell (R-VA) and former Sen. George Allen (R-VA) are backing him.

In 2017, Virginia was a frontier in the culture war, as the fight over Confederate monuments was a topic that became a campaign issue. In a similar vein, Cox has made combatting “cancel culture” a key issue of his campaign — perhaps as an overture to the right.

Businessman Pete Snyder, who lives in Charlottesville, is billing himself as a more conservative alternative to Cox, but as one without the type of baggage that Chase brings. Cuccinelli has endorsed Snyder.

Retired private equity executive Glenn Youngkin suggests that his image as a political outsider would provide a stark contrast to McAuliffe in a general election (assuming Democrats nominate the former governor). Republicans at the convention may also consider Youngkin’s ability to self-fund.

Other candidates in the race include Merle Rutledge, Sergio de la Peña, Kurt Santini, Peter Doran, and Paul Davis. But any Republican who makes it out of the convention will have to be prepared for an uphill campaign against the Democratic nominee. In recent general elections, Virginia Republicans have earned about 45% of the vote, but getting much past that has proved challenging.

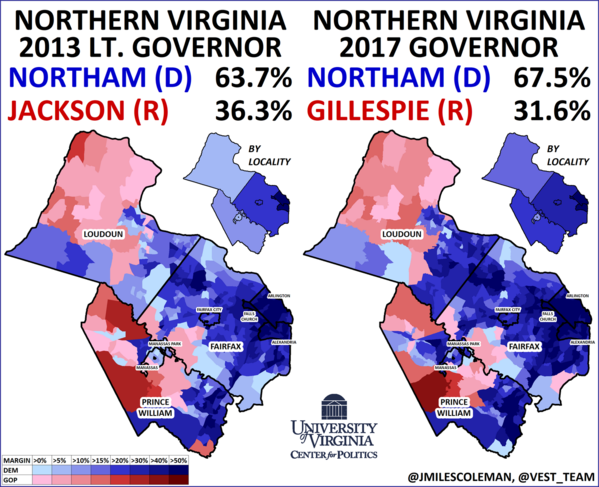

Broadly, the Republican brand has been on the decline in the state’s suburban localities, which are still growing relatively rapidly. Gov. Northam’s statewide career illustrates this shift quite well. In 2013, when he ran for lieutenant governor, his opponent was E. W. Jackson, a Black preacher with a history of inflammatory statements — Jackson beat Snyder for the nomination at a 2013 convention. Northam carried the Northern Virginia area with 64%. Four years later, in his race for governor, he was running against former Republican National Committee leader Ed Gillespie. With a long history in party politics, Gillespie was the type of “establishment” Republican that the Northern Virginia area had traditionally been receptive to. But as Map 2 shows, Northam fared even better in the region against Gillespie, even as he won statewide by less (Northam won in 2013 by nearly 11 points and in 2017 by about nine points).

Map 2: Northern Virginia, 2013 vs 2017

Perhaps without the albatross of Trump, Republicans will be better able to localize the race. Although, in the case of Northern Virginia, with its proximity to the country’s capital, local politics is often national politics. While Virginia Republicans certainly have their work cut out for them, and a Likely Democratic rating would be justified, out of an abundance of caution, we’ll start the race off as Leans Democratic.

Depending on the salience of the local issues this fall and the trajectory of the pandemic, this race might end up being a good test as to whether Republicans can make up ground in suburbia by arguing that Democrats are too close to teachers’ unions on school reopenings.

New Jersey: Democrats favored to (finally) re-elect a governor

In 2021, Garden State Democrats are looking to make some history of their own: even though the state has voted blue in presidential contests since 1992, no Democrat there has been reelected as governor since 1977. Facing voters this year, Gov. Phil Murphy (D-NJ) seems positioned to break that curse.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Murphy’s outlook for reelection was somewhat more dicey, but voters gave him high marks for his handling of the crisis. His recent approval ratings have still been over 50%. Despite its aversion to reelecting Democratic governors, New Jersey is still one of those states where, in order to win statewide, almost everything needs to go right for Republicans.

In 2009, enough factors fell into place for Republicans to deny a Democrat reelection. With an ailing economy and budget shortfalls dominating headlines, then-Gov. John Corzine (D-NJ) spent the lead-up to his reelection campaign fighting with his own party in the legislature. The favorite for the GOP nomination that year was Chris Christie, a plain-spoken former U.S. attorney. At this time in the 2009 cycle, Corzine had a 40% approval and was trailing Christie by nine percentage points. The governor made up some ground by the fall, but still lost by almost four points. A former Goldman Sachs executive with connections in the financial services industry, one of the few advantages Corzine had was in fundraising — altogether better-positioned, Murphy seems fine on that front (as it happens, he is also a Goldman Sachs veteran).

But this isn’t to say Murphy’s tenure as governor has gone perfectly. As with Virginia, Republicans will certainly try to localize the race, and they may have some openings. In 2019, Murphy promised to fix the state’s transit system — “[I’ll] fix NJ Transit if it kills me,” as he put it — but the state’s commuters still face challenges. In the 2017 gubernatorial election, Republicans kept a focus on property taxes, and their nominee, then-Lt. Gov Kim Guadagno (R-NJ) overperformed in several higher-income pockets of the state.

The clear Republican frontrunner is former state Assemblyman Jack Ciattarelli, who came up short to Guadagno in the 2017 primary. In some matters of style, Ciattarelli is borrowing from Christie’s playbook. In a state with a truly distinctive culture, Christie played up his authentic New Jersey persona — he’s quick to mention his affinity for the state’s musical icon, Bruce Springsteen. In his campaign kickoff, Ciattarelli, a native of the state, charged that the Massachusetts-born Murphy, “…doesn’t understand New Jersey.”

This is still a very machine-driven state in primaries. Murphy has no primary opposition, and Republicans will spend the next few months jockeying for the party line in most of the state’s counties. Ciattarelli already has the line in several counties.

New Jersey typically votes more Democratic than Virginia, and given Murphy’s advantages as the incumbent, the Crystal Ball sees this race as less competitive. We’re starting it at Likely Democratic.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.