States of Play: North Carolina

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman and Bennett Stillerman

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— After President Obama’s narrow win there in 2008, light red North Carolina has proved elusive for Democrats — but it remains a target for both sides.

— North Carolina’s politics are increasingly shaped by its growing bloc of unaffiliated voters.

— Over the past decade, North Carolina’s traditional east-west divide has evolved into more of an urban-rural split — a pattern seen in many other states.

— In a state known for volatile Senate races, 2020’s contest should be true to form, and further down the ballot, voters will weigh in on several statewide races.

2008 brings a closely-divided state into play

Affectionately dubbed “The Tar Heel State,” North Carolina, with its divided electorate, is a highly-sought electoral prize. Its current swing status is somewhat of a new phenomenon; Barack Obama carried it, narrowly, in 2008. The state voted almost uniformly Democratic from the end of Reconstruction through 1964, as part of the Democrats’ Solid South. Then, following backlash to President Lyndon Johnson’s civil rights legislation, it stayed largely in the red column from 1968 until 2004, the one exception being when it supported southerner Jimmy Carter in 1976. Overall, Republicans have carried North Carolina in 11 of the last 13 elections — Obama’s victory by three-tenths of a percentage point in 2008 was the only break in what is otherwise a nearly four-decade Republican winning streak.

With a sizable cache of 15 electoral votes up for grabs, both parties would be wise to invest in North Carolina — after the 2020 Census count, it’s expected to gain a congressional seat, which will increase its clout in the Electoral College.

The state sports large metropolitan areas like Charlotte and Raleigh, which have diverse populations. These voters, along with a sizable contingent of rural Black residents scattered throughout the eastern part of the state, are the heart and soul of the Democratic coalition. However, their population is often not enough to outweigh strong GOP support from rural areas throughout the state. Republicans also find support in the exurbs of the major metro areas: Charlotte’s Union County and Raleigh’s Johnston County, for example, are becoming more influenced by their respective metro areas, but GOP candidates routinely clear 60% of the vote in each.

Politically, the relative balance between metropolitan areas and rural communities helps account for the state’s marginal nature. In both the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, it was the country’s second-closest state by percentage margin, and for 2016, it was among a handful of states that Trump carried with less than 50% the vote. This year, the outcome of the election should again rest on that tenuous balance between the urban cores and rural communities — so neither party can take much for granted.

Not surprisingly, the Biden campaign has made significant expenditures in the state, while pro-Trump groups have also prioritized it. Without North Carolina, Trump doesn’t have many feasible routes to 270 electoral votes. Given its persistent light red hue, if Trump has lost there, states that are more “purple,” like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, should already be in the Democratic column. For Biden, carrying North Carolina would likely be, from a purely mathematical standpoint, icing on the cake, though his campaign’s efforts there could boost down-ballot Democrats.

The Crystal Ball currently has North Carolina rated as Toss-up, so we believe that neither party currently holds a clear edge there.

Let’s next dive into key aspects of North Carolina’s electoral history and analyze the demographic and political changes that might give us a clue to which side the Tar Heel State will end up on this year.

Unaffiliated voters reshape state political landscape

North Carolina voters have become increasingly disaffected with the major political parties, at least in terms of party registration. The dynamics of statewide elections are more dependent on which candidate Unaffiliated voters support — but this was not always the case.

As part of the old Solid South, Democrats held an advantage in North Carolina voter registration, but that didn’t always equate to electoral success: As suggested above, Republicans have won 11 of the last 13 presidential contests there. How do we make sense of this? The answer is a simple intuition: Party registration does not equal party identification.

With the advent of Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy in 1968, the Democratic Party lost its stranglehold on southern politics. Nixon carried North Carolina with a 40% plurality — while independent George Wallace and Democrat Hubert Humphrey took about 30% apiece — and then he took close to 70% in his 1972 landslide. But voters were slower to change their registration to match their federal voting preferences. As of the 1974 Almanac of American Politics, 73% of the state’s voters were registered Democrats. So the disconnect between party registration and voting preference has factored into state elections for decades.

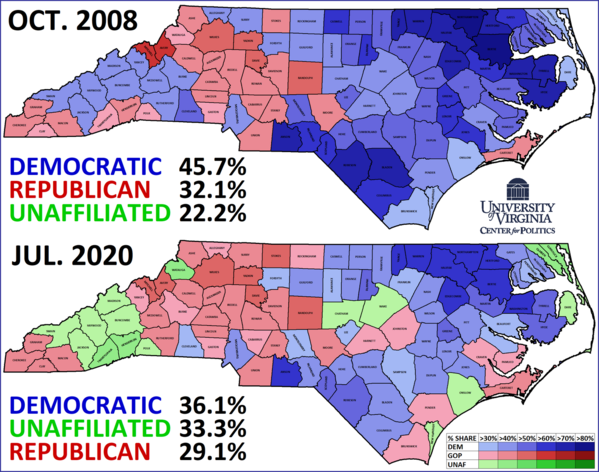

When Obama carried the state in 2008, the composition of the electorate was considerably different than it is now. In short, things were more two-party: In Oct. 2008, Democrats claimed 46% of voters, while Republicans took 32% and the remaining 22% were Unaffiliated. Roughly a dozen years later, Unaffiliated voters have supplanted Republicans, and could potentially outnumber Democrats soon (Map 1).

Map 1: NC voter registration by county, 2008-2020

In 2008, aside from the two parties and “Unaffiliated,” the only other option voters could select when registering to vote was the Libertarian Party. With 3,100 registered voters out of the state’s 6.2 million, the Libertarians were not a significant bloc at the time. Since then, the state has recognized the Green and Constitution parties, perhaps speaking to the appetite voters have for options beyond the two major parties. Together, Libertarian, Green, and Constitution Party members make up 1.5% of registered voters today.

As of July 2020, 16 counties are plurality-Unaffiliated. They’re spread throughout the state but have some common characteristics. Generally, the green counties on Map 2 tend to be rapidly growing. In terms of population size, Wake County has long played second fiddle to Mecklenburg County, but after years of more robust population growth, Wake became the largest county in 2019. Perhaps not surprisingly, Wake is plurality-Unaffiliated.

Some of the plurality-Unaffiliated counties contain public colleges: Buncombe (UNC-Asheville), Jackson (Western Carolina University), New Hanover (UNC-Wilmington), and Watauga (Appalachian State University) are examples. Wake County’s neighbor to the west, Chatham County, has seen an influx of new residents as communities closer to Raleigh have filled up, and it is just a few miles from both UNC-Chapel Hill and Duke University (those colleges sit in heavily-Democratic Orange and Durham counties, respectively). With that, it makes sense that, according to Carolina Demography, the state’s Unaffiliated voters are more likely to be millennials.

Carolina Demography also notes that, since 2016, the state has added just over a million registered voters — members of minority groups such as Hispanics and Asians have tended to account for a disproportionate share of new Unaffiliated registrants. Perhaps as a consequence of these groups registering as Unaffiliated at a greater clip, the Democratic share of the registered voter pool has dropped faster than the Republican share. One conclusion may be that millennials, including younger minority voters, will vote blue in elections, but otherwise don’t much care to be associated with party politics. Michael Bitzer of Catawba College confirms this, noting that, “Democrats may see greater numbers and loyalty among these voters,” as millennial Unaffiliated voters swamp the electorate.

Counties that have remained most faithful to the major parties are also heavily-minority, though their economic picture seems to play a role. In the northeastern corner of the state, Edgecombe (16%), Warren (20%), and Hertford (21%) counties have the lowest percentage shares of Unaffiliated voters in the state. Taken together, their aggregate population is nearly 60% Black, and each county is between 65%-70% Democratic by registration. However, they’re also three of the poorest and least transient counties in the state — the northeast has struggled to attract the type of new residents who have registered as Unaffiliated in large numbers in the booming metros.

The influx of new voters into the ranks of the Unaffiliated bloc may change the group’s electoral behavior. Previously, Unaffiliated voters were part of more conservative generations, and thus skewed more Republican. Exit polling seems to confirm this: self-identified independent voters in North Carolina supported John McCain 60%-39%, Mitt Romney 57%-42%, and Trump 53%-37% (in the context of polling, the terms “independent” and “unaffiliated” are often used interchangeably). So Republican support among these voters has declined a bit, but what does this tell us about 2020?

The polling in 2020 suggests that this trend has accelerated. A New York Times/Siena College poll conducted in mid-June pegged unaffiliated voters as pro-Biden by a 49%-31% margin. Public Policy Polling, a Democratic pollster which is based in the state, also found that unaffiliated voters support Biden, but by a much more narrow 47%-46%. Swings among unaffiliated and/or independent voters can certainly decide elections. Earlier this year, National Public Radio reported on the impact of unaffiliated voters in states like Colorado, Florida, and Arizona.

It’s tempting to think about unaffiliated voters as a monolithic, anti-partisan group, but this would be an oversimplification. Monmouth University, a respected pollster, addressed this. Monmouth concluded that unaffiliated voters can rely on partisanship less when making decisions — that does not mean that their partisan leanings play no role, rather that other factors carry more weight with unaffiliated voters. This year, Trump’s divisive behavior and mismanagement of the coronavirus may be decisive in pushing unaffiliated voters to the Democratic Party. The last time there was a crisis of this magnitude during an election year, Barack Obama became the first Democrat to win North Carolina since 1976.

East/west becomes urban/rural

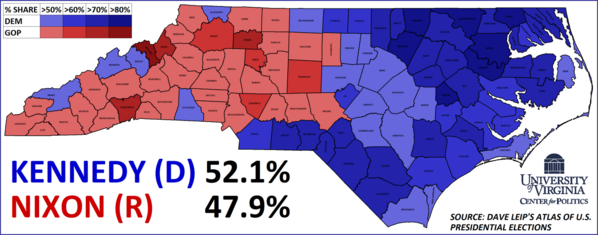

Historically, North Carolina featured something of a geographic tug-of-war: Democrats would rack up huge margins out east, while, if Republicans wanted to compete, they’d have a base in western counties — the Republican Party has had enduring strength in western North Carolina since the Civil War (both it and eastern Tennessee had a lot of pro-Union sentiment in the war). The 1960 presidential election illustrates this: as part of his razor-thin national margin, John F. Kennedy carried North Carolina by four percentage points. (Map 2)

Map 2: 1960 presidential election in North Carolina

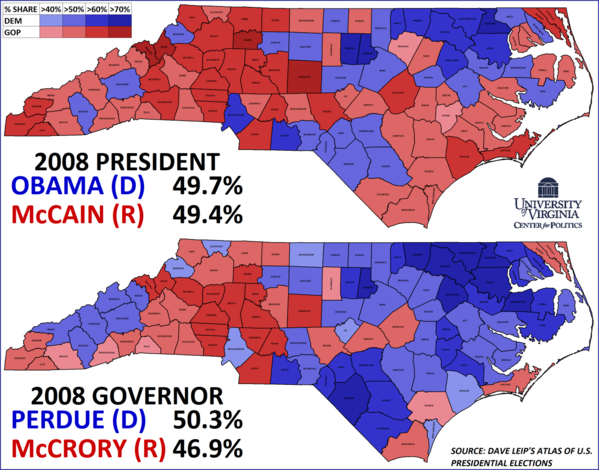

A half-century later, 2008 was something of a transitional year in North Carolina’s electoral landscape. If Obama’s close win in the state was a sign of national change, at the state level, voters simultaneously endorsed the status quo in Raleigh by elevating then-Lt. Gov. Bev Perdue (D) to the governor’s mansion. Both races broke the Democrats’ way, but a split was notable. Obama carried the state by turning out minority voters in unprecedented levels, while making major inroads in suburbs. Perdue, who had been in state government for almost two decades, was from the east — her down-to-home accent was apparent in her ads — and put together a Kennedy-esque coalition. (Map 3).

Map 3: 2008 presidential and gubernatorial elections in North Carolina

Perdue’s opponent was Pat McCrory, the then-incumbent mayor of Charlotte. Over his 14 years as mayor of the state’s largest city, he fashioned himself as an independent-minded “Eisenhower Republican” — this was a contrast to Perdue, and that image paid some dividends. Mecklenburg County, which cast over 400,000 votes that year, supported Obama 62%-37% but McCrory lost it by just 337 votes. McCrory, with his reformer image, also played well with suburban voters outside of Charlotte — as Obama carried Wake County 57%-42%, he held Perdue to a 51%-45% edge there. But Perdue made up for that by carrying 27 counties that supported McCain, the bulk of which were located out east. So while Obama gave national Democrats a blueprint to win North Carolina, Perdue’s election was very much the last truly “traditional” map.

Going forward, Obama’s winning coalition in 2008 may be instructive for Biden in 2020. Though Biden has very much run on his association with Obama, he likely won’t be able to replicate Obama’s historic levels of enthusiasm with Black voters — though perhaps running mate Kamala Harris, a Black candidate, could help. Still, Biden may be able to run up the score with another group: affluent white professionals. Often originally from other states, this group dominates North Carolina’s suburbs, like the South Charlotte area and Wake County’s Cary (it’s a running joke that the city’s name is an acronym for “Containment Area for Relocated Yankees”).

As the 2018 midterms demonstrated, the GOP is going to have a tough time in 2020 if they continue to hemorrhage votes from suburban areas. In 2008, the state’s 9th Congressional District, which then centered on suburban neighborhoods in south Charlotte, was reflexively red at all levels of government — Republicans have since seen serious slippage in the area. It’s a good bet that Biden’s campaign will rely heavily on these voters.

Another sure bet for 2020 is that state-level results will take on a more nationalized character. Again, let’s consider the ballad of Pat McCrory. After her 2008 victory, Perdue saw negative job approval ratings from essentially the start of her tenure. With Perdue struggling to make a positive impression on voters — in 2010, the legislature flipped Republican, further weakening her hand — it was an open secret that McCrory, who had a certain “I told you so” factor on his side, was going to run for a rematch. Perdue ended up retiring in 2012, and McCrory waltzed to an easy win that year.

Once in office, the pragmatic McCrory was pushed rightward by an ideological legislature, as he ended up signing several conservative bills, ranging from voter ID legislation to tax cuts. In March 2016, he signed House Bill 2, which would become commonly known as the “Bathroom Bill.” The bill was seen as having anti-LGBT intent, and prompted some businesses to boycott the state — most notably, for a state where basketball is sacrosanct, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).

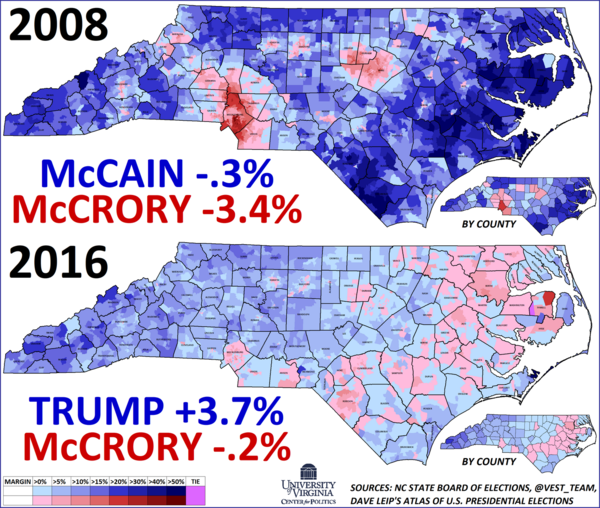

Even before HB2 became a national story, McCrory had drawn a top-tier opponent in popular state Attorney General Roy Cooper (D-NC). It’s rare that statewide candidates, from either party, win with over 60% of the vote, but Cooper took 61% in his 2008 reelection and was unopposed in 2012. In a result that went to a recount, Cooper won the governorship by 10,000 votes, or two-tenths of a percentage point. For McCrory, it had to feel like a familiar situation: in both 2008 and 2016, he ran a little over three percentage points behind his party’s presidential nominee. (Map 4)

Map 4: McCrory vs GOP presidential nominees, 2008 and 2016

Though there were some regional factors still at play in 2016, the depth of the crossover vote became much more shallow. In the suburbs of Charlotte and Raleigh, McCrory performed markedly better than McCain, but ran over 50 percentage points behind in some rural eastern precincts. For 2016, McCrory and Trump were within 10% of each other in the majority of precincts, so the shades of red and blue are lighter.

Trump’s 29% deficit in Mecklenburg County made him the worst-performing Republican presidential nominee there since in 1944, and Charlotte’s “Mayor Pat” did only slightly better than Trump in the area. One of the more visible blows to McCrory’s hometown image was that, to protest HB2, the National Basketball Association pulled its 2017 All-Star game from Charlotte. Perhaps a more local factor that hurt McCrory in the northern precincts of the Charlotte region was his support for toll roads — something unpopular with commuters.

As with McCrory, Cooper actually didn’t have much of a home region vote, either. Cooper hails from Nash County, which sits just east of Raleigh. Roughly 40% Black by composition, it’s one of the few true swing counties in the state, though it recently followed something of a countercyclical trend: it was one of about a dozen counties, nationally, that supported McCain in 2008 but then flipped to Obama for 2012. Lacking Obama’s historic Black support, Clinton lost Nash County, but by just 84 votes. Given the presidential margin, Cooper’s 52%-47% vote there seemed underwhelming. From 1987 to 2001, he represented it in the legislature, and during his three contested races for Attorney General, he never took less than 69% in his home county.

In something of an irony, considering where he underperformed most in his original statewide run, McCrory ran ahead of Trump in much of eastern North Carolina. This was a historical anomaly, as recent GOP candidates for governor would struggle there, even while eastern counties had been supporting Republican presidential nominees for decades. Shortly before the 2016 election, Hurricane Matthew blew through the region, causing severe flooding. From an optics standpoint, McCrory earned some positive press during the storm’s aftermath — considering the final margin, it may have nearly saved him. Still, even considering any of Hurricane Matthew’s likely effects, it was clear that the old east/west electoral split in the state was done. If anything, McCrory’s underperformance in western North Carolina may be a sign that longer-term, the mountains may see more investment from Democrats than the Coastal Plain.

This year, Cooper, in part due to his handling of the pandemic, is a clear favorite for reelection. More often than not, polls have found the governor with double-digit leads over his GOP opponent, Lt. Gov Dan Forest (R-NC). With Cooper’s prospects looking strong, the Crystal Ball rates the race as Likely Democratic, and Democrats are hoping that his coattails will be enough to gain seats in the legislature. Republicans have controlled both chambers of the legislature since the 2010 elections, and they’re each at least somewhat in play.

In contrast to Wisconsin — in our profile of the state last week, we noted that it has few major non-presidential races this year — North Carolina elects a slate of ten statewide officials in presidential years, known collectively as the Council of State.

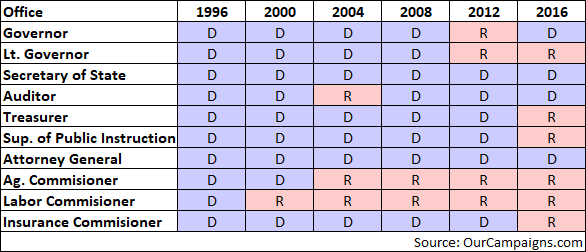

Given the state’s Democratic heritage, the GOP didn’t hold any of the 10 offices after the 1996 elections. In 2000, then-state Rep. Cherie Berry (R) was elected Commissioner of Labor, which opened the floodgates for the GOP in the 21st century (Table 1). As an aside, though she’s retiring for 2020, Berry is something of a celebrity with local political observers — her picture is in every elevator in the state, which some research suggests has aided her in elections.

Table 1: NC Council of State by party affiliation

In 2016, Republicans captured six of the 10 offices — the first time they could claim a majority on the Council of State since Reconstruction. Still, five races, including the gubernatorial contest that year, were essentially coin flips. Assuming the presidential result in the state is close, 2020’s statewide results could be similarly volatile.

Unaffiliateds may decide Senate race, too

While North Carolina Democrats have, all things considered, benefited from the scheduling of statewide elections in presidential years — in the Obama era, the Black turnout he inspired also helped lift down-ballot Democrats — Republicans, on the whole, have gained from the timing of the state’s U.S. Senate seats. Both 2006 and 2018, two of the biggest Democratic wave years in recent decades, were “blue moon” years in North Carolina, meaning that there were no statewide executive or Senate races those years. If the state had a Class I seat — Crystal Ball Senior Columnist Louis Jacobson explored the composition of Senate classes in a recent article — it would have been easy to imagine a Democrat winning that seat in the anti-George W. Bush election of 2006, retaining it by running a few points ahead of Obama in 2012, and then enjoying a favorable national environment in 2018.

Instead, the state’s senior senator, Richard Burr (R-NC) has kept a low profile for most of his tenure but won his three elections in years that were favorable to Republicans. In 2004 and 2016, he faced a presidential electorate, but was helped, to some extent, by his party’s nominees. In between those years, he drew a credible opponent in longtime Secretary of State Elaine Marshall (D-NC) in 2010, but in an anti-Obama midterm, the race wasn’t a priority for national Democrats.

Favorable timing also helped the late Sen. Jesse Helms (R-NC). One of North Carolina’s most famous and polarizing national figures, Helms won five terms in the Senate. With a penchant for antagonizing liberals, he was swept into office in 1972 on Richard Nixon’s coattails. His closest race was in 1984, against then-Gov. Jim Hunt (D-NC), who was then concluding a successful eight-year tenure in Raleigh. In what was dubbed the ugliest campaign in the country, Helms pulled out a narrow win by constantly tying himself to President Reagan, who carried the state by 24% that year.

Helms’ old seat is now held by first-term Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC). If Unaffiliated voters are going to decide the election, Tillis may have a tough battle for their support. Earlier this week, polling from Morning Consult gave Democrats’ nominee, former state Sen. Cal Cunningham (D-NC), a 47%-39% lead, which included a 41%-34% advantage with independents. Though GOP partisans may ultimately come home, Tillis must also work to shore up his right flank — while a near-unanimous 93% of Republicans are backing Trump in that poll, only 78% support Tillis.

Polling has usually shown a high amount of undecided voters, especially compared to the presidential race, so the race may be fluid. In 2014, the year Tillis was elected, most polling had the late Sen. Kay Hagan (D-NC) with a small, but consistent leads throughout the campaign. Unfortunately for Hagan, most undecided voters broke for Tillis late in the cycle. This year, the North Carolina contest is one of just three Senate races that the Crystal Ball considers a Toss-up.

Overall, no other state appears to have as many important and competitive races this year as does North Carolina. It is the only big state to feature competitive races for president, Senate, and governor. It also has new congressional and state legislative maps, which will allow Democrats to net at least two new U.S. House seats and could threaten GOP majorities in the state legislature.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.