Republican Governors Draw Primary Challengers, But History Suggests They Face Long Odds

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman

Checking in on gubernatorial races in Georgia, Massachusetts, Ohio, Texas, and elsewhere.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— With months to go until the 2022 gubernatorial primaries, several Republican governors have drawn notable primary challengers.

— Still, it is relatively rare for sitting governors to lose renomination, and all GOP incumbents appear to be favored in their primaries.

— Most, though not all, Republican primary challengers who have emerged are running to the right of their incumbents.

— While we’re holding off on making any ratings changes for now, any primary upsets may prompt us to reevaluate some races.

2022 Republican gubernatorial primaries take shape

It’s been almost exactly four months since the Crystal Ball launched our initial 2022 gubernatorial ratings. While we’ve written quite a bit about the race developing in our home state, Virginia, this calendar year, there are three-dozen states that will hold contests next year. Though we won’t be making any ratings changes at this point, some of the developments in key races deserve attention.

One theme so far this cycle is that several incumbent Republican governors, from across the GOP’s ideological spectrum, have drawn primary challengers who are at least somewhat credible.

Still, it is rare for incumbent governors to lose primaries. The last time more than two incumbents lost a primary in any even-numbered year was 1954, and the last time more than one lost a primary was 1994. That said, at least one incumbent has lost renomination in each of the last four midterms.

Georgia and Texas

One of the first governors to draw a challenge was Georgia’s Brian Kemp, who originally won his post in 2018. With the help of then-President Donald Trump in the primary, he went on to defeat the Democratic nominee, former state House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams, in a close race. But Kemp made two moves, which bookended the 2020 election cycle, that gave Trump loyalists reason to grumble: in late 2019, he snubbed Trump’s preferred choice for a Senate appointment, then, as the 2020 calendar year wound down, he insisted that his state’s tally in the presidential contest — which showed now-President Biden carrying the state — was accurate. The latter move, in particular, infuriated Trump. Kemp was booed at a state GOP convention last month, although he came out of the confab still appearing formidable, according to David Siders and Maya King of Politico.

Since our initial look at the race, former state Rep. Vernon Jones has entered the primary. Hailing from DeKalb County, he served as a Democrat in state and local office, on and off, beginning in 1993, before making an appearance at the 2020 Republican National Convention to endorse Trump. Jones switched from Democratic to Republican and is running as a Trumpier alternative to Kemp. However, Kemp retains a sizeable fundraising advantage, making him seem like a clear favorite. Assuming Kemp is renominated, he’ll likely face a rematch with Abrams — though she hasn’t announced any 2022 plans, it’s considered an open secret that she has her eyes on the governorship.

In Texas, a similar situation seems to be unfolding. As Gov. Greg Abbott (R-TX) gears up to seek a third term, he’s faced some challenges. His leadership was criticized earlier this year during a winter storm, although a majority of voters ended up giving him high marks on handling the crisis. A late June poll from the Texas Tribune puts Abbott’s approval/disapproval at a neutral 44/44 spread — ostensibly not great, but all other statewide officials were on slightly negative ground.

In fact, going into this cycle, it seemed that any potential challenge to Abbott may have come from another statewide row official. Instead, former state Republican Chairman Allen West, who is — like Vernon Jones in Georgia — a Black Republican, got into the primary last month. West spent the last year leading the state GOP, but if his name sounds familiar to political observers, it’s because, a decade ago, he was serving as a congressman from the Palm Beach area in Florida. In 2010, West embraced the Tea Party movement and ousted a Democratic incumbent in a swing seat. Two years later, though, running in a redrawn seat, West was ousted himself — it was the cycle’s most expensive House contest.

In a state as transient as Texas, West’s carpetbagging may not even be his biggest liability. Rather, there simply doesn’t seem to be much of an appetite for replacing Abbott, at least among Republicans: the Texas Tribune poll found his approval at nearly 80% within his own party.

West is not Abbott’s only primary challenger. In May, former state Sen. Don Huffines got into the GOP primary. With a base just north of Dallas, Huffines served one term in the legislature — in 2014, he primaried a more moderate incumbent, but was swept out in 2018, as the pro-Democratic swing in the suburbs that year crashed especially hard in the area. Huffines has shown some fundraising strength: He’s raised $9 million since getting into the race. If this were an open-seat race, a figure like that would likely put him in a much better position. But even that sum is dwarfed by the $55 million that Abbott has in the bank.

Looking to the general election, Texas Democrats have a few disadvantages compared to their counterparts in Georgia. First, while it’s been a poorly kept secret that Abrams is intent on seeking a rematch, most state observers expect her to eventually run — anticipating her candidacy, no other Democrats have entered the contest, The Democratic primary in Texas seems to be in a somewhat similar state of limbo, though it’s possible Democrats may not end up with their best-known candidate. Former Rep. Beto O’Rourke (D, TX-16) held Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) to a close margin in 2018 and has remained very active in state politics after a failed bid for president. O’Rourke is considering the race, and many Democrats seem to be deferring to him — but he’s emphasized that the state filing date is “not until December,” and doesn’t seem to be in much of a rush to decide.

Actor Matthew McConaughey, a Texas native, has taken some steps towards running — and he’s even polled ahead of Abbott in some hypothetical matchups — though it’s not clear that he’d run under the Democratic banner. If McConaughey runs as an independent, will Democrats line up behind him? Some comparisons have been drawn to the state’s 2006 gubernatorial election: in a field with four major candidates, then-Gov. Rick Perry (R-TX) won with just a 39% plurality, as Democrats blamed an independent candidate, musician Kinky Friedman, for pulling votes away from their candidate. Considering that McConaughey has polled better with non-Republican voters, if he runs as an independent, there could be some creative maneuvering on the part of state Democrats, especially if they can’t recruit a prominent candidate of their own.

Additionally, compared to Georgia, Texas is simply a redder state. Though it’s acting increasingly like a swing state in presidential elections, Trump still held the state by about 5.5 percentage points last year. While there are some signs that Trump-era Democratic gains in the state will endure — in 2018, even as Abbott was reelected by double-digits, he couldn’t match the suburban numbers that Mitt Romney received in 2012 — Trump’s impressive 2020 numbers in South Texas may encourage Republicans to make the region more of a priority going forward.

As an aside, one of the bigger national news items this week was that, to block Republican-sponsored legislation, Democrats in the Texas legislature left the state, and many of its caucus members have vowed to stay in Washington, D.C. until a special legislative session called by Abbott ends in early August. Texas is one of the few states with legislative rules that require two-thirds of its members to be present to conduct business — the vast majority of other states require a simple majority, which means that the majority party will always be able to produce a quorum. The legislation that prompted this “walk out” centered on Republican changes to the state’s voting laws.

Democrats staged a similar protest in 2003 — they fled across the border to Oklahoma — which had the effect of delaying a GOP-engineered mid-decade congressional redistricting plan. Despite their tactics, Democrats actually gained seats in the Texas state House after their 2003 walkout, though the new congressional map was enacted for 2004, to the benefit of Republicans. Given today’s fast-moving news cycles, and the fact that the midterms are over a year away, it’s hard to tell what impact this episode will ultimately have on next year’s races, though Democratic candidates will surely continue to emphasize voting rights as an issue on the campaign trail.

Ohio

Republicans in receding battleground states have not been immune to primary challenges, either. Last year, Gov. Mike DeWine (R-OH) was among the first state executives to call for large-scale lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 epidemic. DeWine’s experience in government — he was first elected to local office in Ohio in 1976 — likely informed his more cautious approach to containing the pandemic. While this very well may have been the correct course from a public health perspective, DeWine’s perceived heavy-handedness won him few supporters within his own party. Though DeWine supported Trump in the 2020 election, he blamed the then-president for inciting the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

Last month, former Rep. Jim Renacci (R, OH-16) got into the race, citing the governor’s handling of the pandemic as the main raison d’etre of his campaign. Coincidentally, Renacci, with a Trump-esque “Ohio First” platform, was originally a candidate for governor in 2018 in a multi-candidate primary that featured DeWine. But as it became clear DeWine had the upper hand in that race and after then-state Treasurer Josh Mandel surprisingly dropped out of the Senate race, Renacci ran for Senate instead. Renacci won the Republican nomination but lost the general election to Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) by seven percentage points — even as the rest of the GOP statewide ticket won. In fact, Renacci’s loss to Brown represents the only instance since 2012 that a Republican has come up short in a partisan statewide race in Ohio. Mandel has re-emerged as a candidate in the state’s open-seat Senate race this cycle.

The Crystal Ball continues to see the Ohio gubernatorial race as Likely Republican, in part because DeWine, with his universal name recognition and history in the state, seems favored in the primary. Though Renacci is running as an ardent Trump supporter, it remains to be seen how much the former president will get involved on his behalf, and Renacci has a lot to prove as a candidate after his lackluster Senate bid. Ohio’s semi-open primary system may also boost DeWine, as independent voters may pull ballots for him. Renacci would probably be a weaker general election candidate, though even then, the race may still seem more like a Leans Republican contest than a Toss-up, considering the reddening Ohio has undergone in recent cycles.

One wild card, in both the primary and the general election, is a scandal involving a now-partially-repealed state bailout of a major energy company, which brought down now-former state House Speaker Larry Householder (R). A couple of weeks ago, a book from the late GOP superlobbyist Neil Clark — who died by suicide earlier this year — was released, and it makes a serious charge against DeWine, one that the governor denied through a spokesperson, relating to the bailout.

Though more Democrats may get into the field, their primary is essentially a head-to-head between two mayors from the southwestern part of the state. Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley is making her second attempt at the governorship — she ran in the 2018 Democratic primary for a time, but ultimately dropped out — while Cincinnati Mayor John Cranley is termed out of his current job and is running.

Massachusetts

For much of his term, Gov. Charlie Baker (R-MA) has been one of the most popular governors in the country, despite the deep blue lean of his state. First elected in 2014 as a pro-business and socially moderate Republican, Baker went on to become of one of the leading voices in the anti-Trump faction of the GOP. This independence has unquestionably played well with his state’s overall electorate — a poll from last year found that nearly 90% of Democratic primary voters approved of his job performance. Despite his popularity, Baker has not announced whether he’ll seek a third term (the Bay State doesn’t have term limits for its governors). Judging by an uptick in his still-modest fundraising, he may be gearing up for another campaign, although his lieutenant governor, Karyn Polito, is out-raising him. If Baker opts against a third term, Polito could very well run in his place.

In the meantime, former state Rep. Geoff Diehl entered the Republican primary earlier this month. Known for his (successful) campaign to repeal the state’s gas tax indexing law in 2014, Diehl is a Republican more in line with the party’s base — during the 2016 election, he actively campaigned for then-candidate Trump. In what is becoming something of a theme with gubernatorial primary challengers this cycle, Diehl is a failed 2018 Senate candidate, as he lost 60%-36% to Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA).

In March, we wrote that if Baker chooses to stand for reelection, he’d be a strong bet, regardless of the Democratic nominee. That generally still stands true today, and no big Democrats have gotten into the race. Partisan primaries in Massachusetts are open to unaffiliated voters, and Baker would likely rely heavily on support from independents — fewer than 10% of registered Bay Staters are actually registered with the GOP, and those that are tend to have philosophies closer to that of Diehl’s. If Baker ultimately decides to forgo reelection, that may embolden any number of ambitious Democrats to join the race — against a more conservative Republican, most any Democrat who takes the general campaign seriously would probably start out as a favorite, though Baker himself could be a helpful surrogate for Polito, if she ends up the nominee.

Idaho and Oklahoma

Finally, two ruby red states to watch for primary action next year are Idaho and Oklahoma. While the Crystal Ball rates both contests as Safe Republican, in next year’s primaries, they could offer a study in contrasts.

Idaho Gov. Brad Little (R-ID) has not announced his reelection plans, though he’s expected to run for a second term. Nearly a dozen candidates — most of them lower profile — have gotten into the race, but Lt. Gov. Janice McGeachin (R-ID) stands out. Little, who has generally kept a low profile, is a mainstream Republican, similar to DeWine: He won a competitive 2018 primary, against several more conservative opponents. One key policy difference in that primary was that Little pledged to fund the state’s Medicaid expansion plan if voters approved it in a referendum (it passed with two-thirds of the vote).

McGeachin is positioning herself closer to the party’s grassroots — and she’s not done so without sparking some controversy. Last month, when she briefly assumed the role of acting governor while Little was out travelling, she issued an executive order that rescinded the state’s local mask mandates. Little overturned the order immediately upon his return. Even before her inventive executive order, McGeachin has been criticized as being sympathetic to right-wing militants — Ammon Bundy, an anti-government militant, is also in the primary.

In Oklahoma, Gov. Kevin Stitt (R-OK), generated some negative headlines in March 2020: at the onset of the pandemic, he posted a selfie of his maskless family dining out in a crowded restaurant. Though he eventually took the picture down, critics pointed out the tone deafness. With this in mind, former state Sen. Ervin Yen, a physician by training, got into the race shortly after the 2020 presidential election — Yen cites the state’s handling of the pandemic as a primary reason for running. While Stitt is still a clear favorite, it may be worth watching how much regional appeal Yen has: he is from the Oklahoma City area, which voted for another local candidate (its former mayor) over Stitt in the 2018 primary. On the other hand, Yen lost his own state Senate primary that same year by 20 points.

Conclusion

While some of these challenges may gain traction by the time GOP partisans go to the polls, it is difficult to primary sitting governors. In fact, since 2010, only three have lost: Jim Gibbons (R-NV), Neil Abercrombie (D-HI), and Jeff Colyer (R-KS). Both Republicans, Gibbons and Colyer, were special cases, to some degree or another: Gibbons was the subject of multiple ethics investigations, and Colyer was not elected in his own right (he ascended to the job after his predecessor took a post in the Trump Administration).

Other primaries, on both sides, could heat up as the midterms draw closer. For instance, Gov. Henry McMaster (R-SC) may still face a primary challenge from businessman John Warren, who McMaster beat in 2018. Compared to 2018, fewer governors will be term-limited in 2022, which may naturally lead to a greater volume of challengers to incumbents.

Overall, just five governors have lost primaries since 1996 out of 179 who have sought renomination in even-numbered years. While there is clearly a lot of primary activity on the Republican side of the gubernatorial ledger, we have not seen compelling evidence — as of yet — to believe that any of the aforementioned governors are in very deep trouble.

P.S. RIP Edwin Edwards

While on the topic of governors, we’d be remiss not to acknowledge the passing of Louisiana’s Edwin Edwards. On Monday, the Democrat (who is not related to the current incumbent) died at 93 — by many measures, he was the most colorful governor, from any state, of the last half-century. Eminently quotable, and with a famously cavalier approach to public ethics, Edwards was among the nation’s most experienced state executives, as he led the Bayou State for four terms. His final gubernatorial win, in 1991, was one of the most storied non-presidential races in recent history, so we’ll take a brief look back at that.

Then a congressman from Crowley — a Cajun town that the Almanac of American Politics jests has “produced more prominent politicians per capita than any other place in America” — with a history of supporting civil rights, Edwards first ran for governor in 1971. He won, was reelected in 1975, and then returned in 1983, after term limits forced him to wait four years after his second term concluded. In 1987, he came up short in his reelection bid. As it turned out, his successor, then-Gov. Buddy Roemer (R-LA), seemed vulnerable himself four years later; elected first as a Democrat, Roemer switched parties in early 1991. However, another Republican, then-state Rep. David Duke (R-LA) was gaining steam, despite his past as a grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

As a result of the state’s jungle primary system, where all candidates, regardless of party, run on the same initial ballot, Roemer, who tried earnestly to placate most everyone during his term but wound up with few firm supporters, was squeezed out of a runoff. Roemer ran best with college-educated voters in a handful of parishes across the state, but finished third. Edwards relied on Black voters (in office, he diversified the ranks of state government) and, with his fluency in French, he could typically count on white Catholics in Acadiana. Duke often made not-so covert racial appeals by attacking the welfare state, and found support with blue collar whites, especially in the state’s Protestant north.

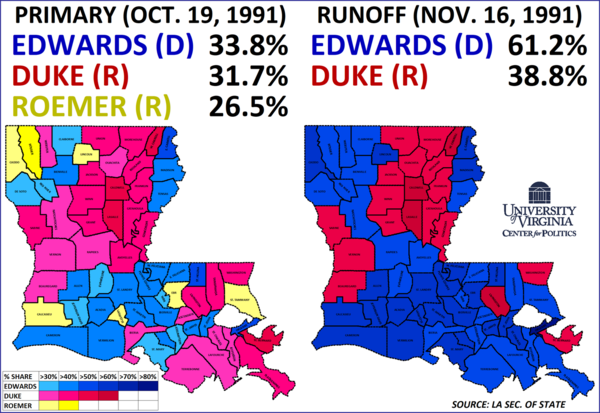

Conveniently for Edwards, the jungle primary was an electoral reform that he instituted during his first term — almost two decades later, it was still working its magic, putting him in a runoff with a toxic opponent. Though some polling showed Duke starting out only a few points behind, his past drew intense scrutiny, and state business leaders warned that adverse economic consequences could be in the cards if the former Klansman won. Many voters held their noses for Edwards: at a runoff debate, the former governor noted that the nature of his opposition enabled him to build a broad coalition that included voters who’d never backed him before. More visibly, bumper stickers across the state displayed the slogan “VOTE FOR THE CROOK: IT’S IMPORTANT.” It ended up a landslide for Edwards (Map 1).

Map 1: 1991 Louisiana gubernatorial election

To his good government critics, Edwards reinforced the perception that big personalities matter more than efficiency in Louisiana. They have some compelling evidence for that claim: though Edwards’ vivid style harkened back to the heyday of the state’s legendary Long dynasty, since he first took office, Louisiana has lost two seats in Congress (it would have still lost representation during that time span even without Hurricane Katrina’s unfortunate impact on its population trends).

While Edwards’ career represented a more recent manifestation of the state’s enduring populist strain, he was still, like all governors, a product of his time. During his earlier terms, in the 1970s, massive oil revenues filled the state’s coffers, providing him ample funds to spend on social programs and infrastructure — he was wildly popular. But by the 1980s, tough economic circumstances made it harder for him to get by on the sheer force of his character. He could not evade his ethical woes forever, either — towards the end of his life, he spent close to a decade in jail. With all his ups and downs, Edwards’ story helps explain what draws many in our profession to politics.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.