The Virginia Gubernatorial Election: Clues from the Past

A Commentary By Rhodes Cook

It is often said that the past is prologue. In that regard, this year's gubernatorial candidates in Virginia--Democrat Creigh Deeds and Republican Bob McDonnell--share a bit of common history. They ran against each other for state attorney general in 2005, a race that ended as one of the closest statewide elections in Virginia history. Following a recount, McDonnell emerged the winner by a margin of just 360 votes out of nearly 2 million cast.

The question is how much that first, razor-close Deeds-McDonnell race can serve as a road map for their rematch this year. Four years ago, they were part of the "under card," overshadowed by the much higher profile race for governor. Since then, Virginia politics has been turned on its head, with a succession of Democratic victories that has arguably transformed the state from bright red to at least the color purple.

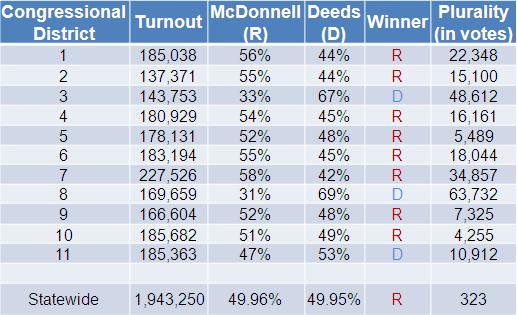

Yet their first contest for attorney general highlighted the generic strength of each party that to a large degree still holds true today. Of the state's 11 congressional districts, McDonnell carried eight, Deeds only three. But the election ended in a virtual tie because McDonnell's strength geographically was broad but not particularly deep, while Deeds' support was concentrated in a small number of places where Democrats dominate.

McDonnell ran best in 2005 in the 7th Congressional District, which extends from Richmond northwest to the Blue Ridge Mountains. The district is currently represented in Congress by a rising star in the national Republican Party, Eric Cantor, and in 2005 it gave McDonnell 58 percent of the vote. In no other district did McDonnell win more than 56 percent.

Meanwhile, Deeds garnered fully two-thirds of the vote in both the black-majority 3rd Congressional District in southeast Virginia's Tidewater and the Northern Virginia 8th. The latter is a liberal suburban enclave along the Potomac River that is represented by Democrat Jim Moran (the older brother of one of Deeds' unsuccessful Democratic rivals this year, Brian Moran).

To this day, the two districts form the basic building block for statewide Democratic victories. In 2005, Deeds won the pair by a combined plurality of more than 110,000 votes. That, plus his 11,000-vote edge in Northern Virginia's 11th District, which includes much of suburban Fairfax County, produced what was essentially a dead heat with McDonnell.

McDonnell-Deeds Round One: A Virtual Tie in 2005

|

Note: The numbers above reflect the vote totals in the race before a recount was undertaken which resulted in a 360-vote win for McDonnell rather than the pre-recount margin of 323 votes. The recount adjusted figures are almost identical to those shown above, but were not available to the state board of elections at the time of publication. |

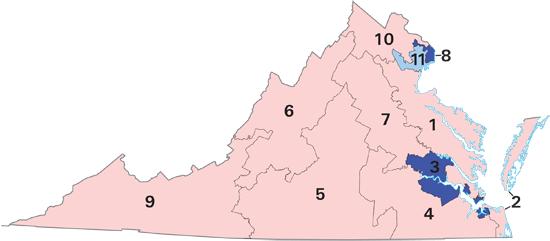

Red districts were won by McDonnell (R), while blue were carried by Deeds (D). Lighter colors indicate that the winning candidate garnered less than 60 percent of the vote.

|

Source: Official results from the Virginia State Board of Elections. |

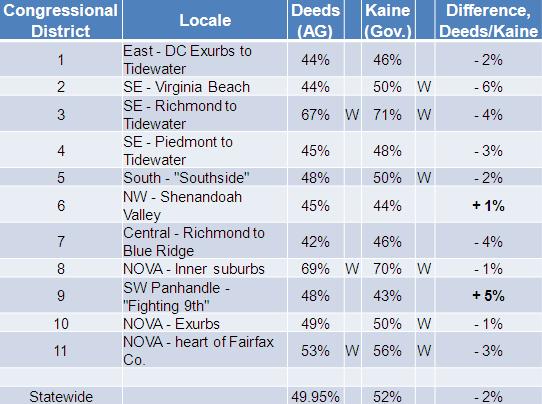

For Deeds, there is probably no better electoral model this time than the present governor, Tim Kaine. Four years ago, Deeds drew 49.95 percent of the vote for attorney general and lost; Kaine polled 51.7 percent of the vote for governor and won comfortably. While Deeds was a little-known rural state senator (and to a large degree, still is), Kaine was a former mayor of Richmond and the sitting lieutenant governor under a popular governor (Mark Warner, now one of the commonwealth's U.S. senators). Kaine was able to present himself as a quasi-incumbent.

Kaine won six congressional districts, twice as many as Deeds. And in only two largely rural districts--the Shenandoah Valley 6th and the western panhandle's "Fighting 9th"--could Deeds draw a higher percentage of the vote for attorney general than Kaine did in his campaign for governor.

In the other districts, Kaine outran Deeds by margins ranging from one to six percentage points, with the largest disparity in the Tidewater 2nd District, which is anchored in McDonnell's home base of Virginia Beach and includes portions of Norfolk and Hampton. There, Kaine won 50 percent of the vote for governor, compared to Deeds' 44 percent share for attorney general.

Deeds and Kaine: The Difference in '05 Between Winning and Losing

|

In 2005, Tim Kaine ran only 2 percentage points better in his race for governor than Creigh Deeds did in his campaign for Virginia attorney general. But Kaine won and Deeds lost, because Kaine succeeded in running a bit better across the state than Deeds did. In his gubernatorial victory, Kaine carried six congressional districts, twice as many as Deeds won in his race for attorney general. And in nine districts, Kaine polled a higher percentage of the vote than Deeds. The two exceptions were the rural 6th and 9th Districts in mountainous western Virginia, where Deeds drew a higher percentage than Kaine. |

|

Note: "W" indicates congressional districts that either Tim Kaine or Creigh Deeds carried in 2005. Listed in bold are the two districts where Deeds drew a higher percentage of the total vote in his race for Virginia attorney general than Kaine did in his contest for governor. |

|

Source: Official results from the Virginia State Board of Elections. |

In the four years since then, Virginia Democrats have been on a roll. In 2006, they picked up a U.S. Senate seat. In 2007, they gained control of the Virginia Senate. And in 2008, they won a political trifecta--taking the other U.S. Senate seat, winning a majority of the state's U.S. House seats, and pulling the Old Dominion into the Democratic presidential column for the first time since 1964. For good measure, Barack Obama's 52.6 percent victory in Virginia nearly matched his national number.

The recent Democratic advance has been fueled by the party's gains in suburban Northern Virginia, which contains the largest jurisdiction in the state, Fairfax County. There, what was a narrow plurality for Republican George W. Bush in the presidential election of 2000 was transformed into a majority of more than 100,000 votes for Democrat Obama in 2008.

But have the Democrats permanently rearranged Virginia's political landscape to their advantage? Republicans think not. President George W. Bush is no longer around to serve as a handy foil for the Democrats. And the energy and enthusiasm that propelled Obama and his ticket-mates in 2008 has seemed to dissipate, at least for the time being.

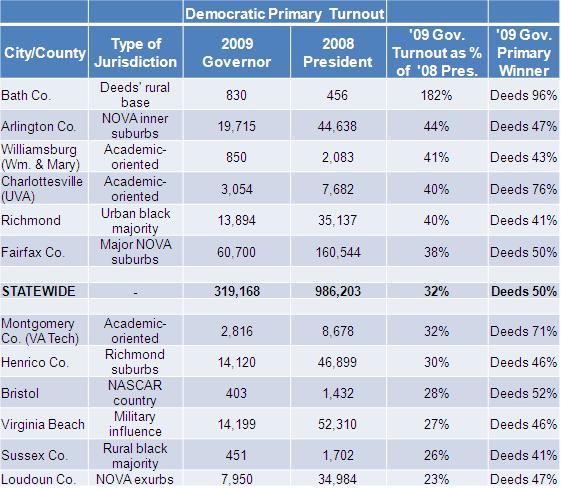

Case in point: nearly one million Virginia voters turned out for the Democratic presidential primary last year, with almost two-thirds of them voting for Obama. Turnout for this June's Democratic gubernatorial primary was only 320,000, even though the field of candidates included a "celebrity" of sorts in the form of former Democratic National Committee Chairman Terry McAuliffe.

Deeds proved to be broadly acceptable to those who cast Democratic primary ballots, taking about half the vote cast, with McAuliffe and Moran almost evenly dividing the rest. As a result, Deeds won practically everywhere, although in many Democratic strongholds he posted plurality, not majority, victories. He narrowly lost the black-majority 3rd District to McAuliffe. In the suburban 8th, Deeds won a 43 percent plurality, actually a rather impressive showing since it is the home base of the politically potent Moran brothers.

The Northern Virginia suburbs, which have trended Democratic of late, will be one of the prime battlegrounds in the fall election. McDonnell was raised in Fairfax County, and in their 2005 race for attorney general was able to beat Deeds in the 10th District, which includes many of Northern Virginia's outer suburbs.

Meanwhile, with his rural roots and "pro-guns" stance, Deeds hopes to poach some votes in the villages and small towns of Virginia--a portion of the state that is often hostile to Democrats.

Virginia's one-term limit on its governors virtually ensures a competitive open seat race every four years for the state's highest office. Even if it were not one of only two gubernatorial elections this fall, the rematch between McDonnell and Deeds would be a campaign worth watching.

'09 Democratic Gubernatorial Primary: Where They Voted ... and Where They Didn't

|

Last year nearly 1 million Virginia voters cast ballots in the Democratic presidential primary, won easily by Barack Obama. This year less than one-third that number participated in the party's gubernatorial primary that was won handily by state Senator Creigh Deeds. The proportion of Democratic primary voters this year compared to last tended to be highest in Democratic strongholds such as Arlington, Charlottesville Richmond, as well as Deeds' rural base of Bath County. On the other hand, there was often a much lower proportion of primary voters this year in cities and counties that are either politically marginal or lean Republican. As for Deeds, he won virtually everywhere, but was particularly strong in the more rural western half of the state. Following is a comparison of 2008 and 2009 Democratic primary turnouts in a sampling of a dozen cities and towns across Virginia that were picked to reflect the array of constituencies within the state. |

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.