Trump Not Immune to the Usual Down-Ballot Presidential Penalty

A Commentary By Louis Jacobson

But the Senate remains a bright spot for Republicans amidst decline elsewhere.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— After just three years in the White House, Donald Trump is seeing a significant erosion of down-ballot seats held by his party.

— This erosion puts Trump in good company — at least since World War II, presidents typically experience at least some erosion across his party’s numbers of U.S. Senate, U.S. House, gubernatorial, and state legislative seats.

— The best news for Trump and Republicans is that they have held their own in the category of races that is arguably most politically important: the Senate.

The down-ballot White House blues

On Monday, President Donald Trump began his fourth year in office. His presidency has been unique in many ways, but he’s been like other presidents in at least one respect: His party has generally lost ground down the ballot since he took office.

In recent decades, presidents have typically seen an erosion of their party’s seats in the U.S. Senate, U.S. House, the governorships, and the state legislatures. In fact, to one degree or another, every post-World War II two-term president has bled seats in these categories, and so have the two-term, same-party combinations of John F. Kennedy-Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon-Gerald Ford. One-term president Jimmy Carter also presided over steep losses, while fellow one-termer George H.W. Bush saw only small gains in the House and in state legislatures.

“The surest price the winning party will pay is defeat of hundreds of their most promising candidates and officeholders for Senate, House, governorships, and state legislative posts,” this newsletter’s editor, Larry J. Sabato, wrote in 2014. “Every eight-year presidency has emptied the benches for the triumphant party, and recently it has gotten even worse.”

The Crystal Ball last looked at this phenomenon after the 2016 election, when we noted the massive scale of down-ballot losses under President Barack Obama. Here, we update the figures to reflect Trump, using the same methodology.

The pattern under Trump is clear: In just three years, Trump is presiding over down-ballot seat erosion for Republicans that, in some categories, is approaching the scale of what his recent predecessors experienced over a full eight years.

Let’s take a look at the numbers.

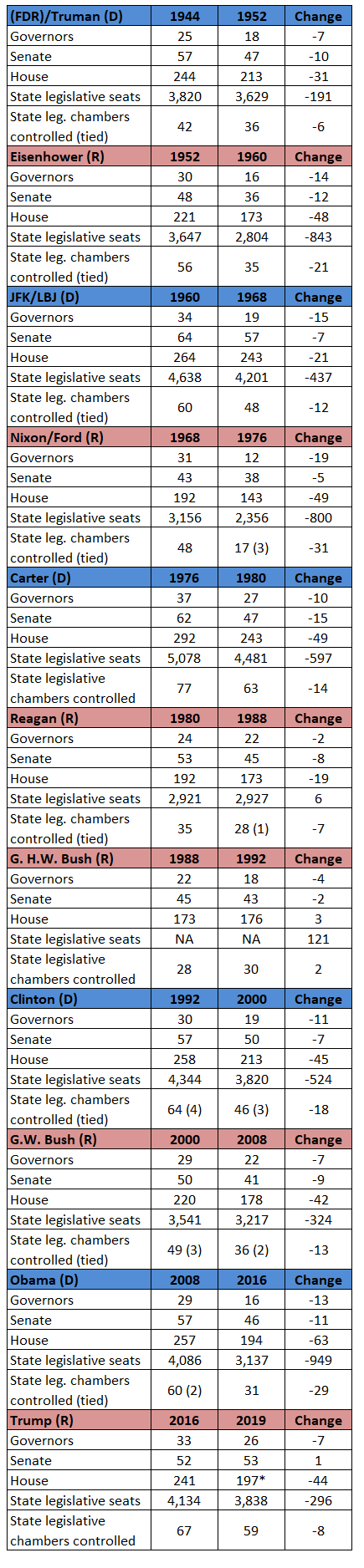

Table 1: Down-ballot partisan change for postwar presidents’ parties

Note: *This includes current vacancies.

In the Senate, Trump was fortunate in 2018 to have a highly favorable map for Republicans — this enabled him to survive his first midterm election with a net gain of one Senate seat.

Beyond that, though, Trump’s down-ballot losses have mirrored those of his predecessors, especially his most recent ones. Here’s a comparison of Trump’s down-ballot losses to those under President Bill Clinton, President George W. Bush, and President Barack Obama:

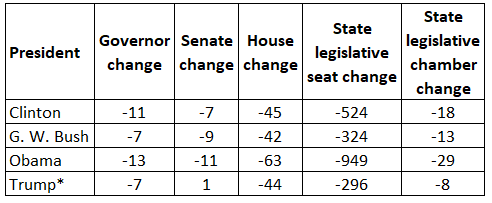

Table 2: Down-ballot change under most recent presidents

Note: *First three years only.

Beyond the unusual results in the Senate — where Trump’s party is actually up a seat so far — Trump’s three-year losses for the other offices are quite close to those experienced over eight years by the younger Bush, the only other Republican in this chart.

Losses under the recent Democrats — Clinton, and especially Obama — have mostly been larger than those under Bush.

One explanation could be that the Democrats experienced a wholesale loss of seats in an entire region — the South — that is unlikely to swing back any time soon. By contrast, suburban losses for Republicans, a comparable seismic event for the GOP, only really accelerated beginning in 2016, meaning they could snowball the same way in the years ahead.

Another explanation could be that voters in midterm elections tend to be older, whiter, and more conservative, which would give Republicans some protection from midterm headwinds.

Why do presidents suffer down-ballot losses so consistently? The biggest factor is likely the public’s fatigue with the president’s party and the policy decisions it has made. With only a small number of exceptions, voters have regularly punished the president’s party in midterm elections, seemingly registering their displeasure with the status quo. Indeed, staying comfortably in power is hard: Only once since World War II has one party won three consecutive presidential elections — the Republicans from 1980 to 1988, when Ronald Reagan won twice and his vice president, George H.W. Bush, succeeded him.

As I speculated in Governing in 2014, “Presidents try to accomplish things, but not everyone likes what they do. Even if they have support from the majority of voters, it’s always easier for critics — even if they’re in the minority — to block major initiatives than it is for supporters to pass them. Once a president’s agenda has been blocked, their supporters grow disappointed, joining critics in their unhappiness. The president’s overall approval ratings sag, and voters take out their anger on whichever party that controls the White House.”

Exacerbating this is the tendency for presidents to accumulate popularity-sapping scandals the longer they stay in office, from Nixon’s Watergate to Reagan’s Iran-Contra to Clinton’s Monica Lewinsky. Not only do such scandals sour voters on the president’s party, but presidents who are fighting for their own political standing don’t have a lot of political capital to share with those from their party who serve at lower levels. By becoming the first postwar president to face impeachment in his first term, Trump has reached this stage at hyper speed.

It’s important to note that it’s premature to say how punishing Trump’s down-ballot losses will be by the time he leaves office. For starters, Trump may not win reelection, which would keep him from reaching the two-term threshold, and the usual presidential down-ballot penalty would transfer to the Democrats. In addition, it’s unclear how much of a positive coattail effect Trump will have on fellow Republican candidates in 2020; a president’s party typically fares better in down-ballot races when the president is on the ballot themselves.

Still, it’s fair to say that while Trump took an unconventional path to the White House, he’s looking very much like his predecessors in presiding over difficulties down the ballot. The White House is very much worth winning, but generally speaking, there are consequences for holding it.

Louis Jacobson is a Senior Columnist for Sabato’s Crystal Ball. He is also the senior correspondent at the fact-checking website PolitiFact and was senior author of the 2016, 2018, and 2020 editions of the Almanac of American Politics and a contributing writer for the 2000 and 2004 editions.

See Other Political Commentary.

See Other Commentaries by Louis Jacobson.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.