The Fundamentals: Where Are We in This Strange Race for President?

A Commentary By Larry J. Sabato, Kyle Kondik and Geoffrey Skelley

And can Trump breach Fortress Obama?

Every presidential election is different, but nobody’s going to tell us that this one isn’t notably different from any other in the modern period.

It’s not just that the two major-party candidates are so disliked and unpopular with much of the public. While Donald Trump’s numbers are no better and sometimes worse, Hillary Clinton’s unfavorables are about as bad as we’ve ever seen for a frontrunner, with about three in five voters saying she’s not honest and trustworthy, a product of the stories about the Clinton Foundation, her private emails, and decades-long controversies involving Clinton and her husband, the former president. Trump got some of the best polls he has enjoyed of the entire cycle on Wednesday, taking leads in the must-win (for him) states of Florida and Ohio. Clinton is struggling with concerns about her health, and her status as the frontrunner in this race is eroding. Perhaps she can pull herself out of her tailspin, and the upcoming debate on Sept. 26 should be a big moment. If she continues to sink, the electoral map we have long tilted in her favor will be getting a lot redder.

Nonetheless, the defining difference in this election is not Clinton but Trump. Forget Wendell Willkie: There has never been a presidential nominee like him. He has divided the Republican Party — separating party elites from much of the party’s populist base — and he has rearranged the electorate in ways we haven’t ever seen, at least to this extent. Minority groups appear to be rejecting him by margins as bad or worse than recent GOP nominees. Trump is having trouble winning a group that is normally quite Republican: college-educated whites. At the same time, he has drawn very sizable, exceptionally intense backing from non-college whites and, disproportionately, blue-collar white men, and he has the potential to out-perform Mitt Romney’s 2012 showing among that group.

Regular readers will have noticed that we have been publishing political scientists’ predictive models for 2016, the quadrennial attempt to use certain variables to project the election results (at least the popular vote) months in advance. We’re publishing our final update on these models this week. They are mostly derived from election fundamentals that don’t change much over time — economic conditions, the number of consecutive terms a party has held the White House, and so on. Averaging all the forecasts together shows a two-party vote of Clinton 50.5% and Trump 49.5%. Obviously, that’s very close, and taken together these models produced a very similar prediction in 2012 (Obama 50.2%, Romney 49.8%). That undersold Obama, who won with 52.0% of the two-party vote.

The problem in 2016 is that the assumptions that undergird some models are disputable. Take our senior columnist, Alan Abramowitz of Emory University. His “Time for Change” model has an admirable record of prediction over many years, nailing the popular-vote winner in every cycle going back to 1988. Yet this time, Abramowitz has declared that his model will probably miss the mark. Why? As Abramowitz explains it, the assumptions upon which the model is built are unsound: “First, that both major parties will nominate mainstream candidates capable of unifying their parties and, second, that the candidates will conduct equally effective campaigns so that the overall outcome will closely reflect the ‘fundamentals’ incorporated in the model.”

Abramowitz’s model predicts a modest Republican victory this November, and considering Clinton’s myriad weaknesses and a competitive political environment, it is easy to imagine it if the GOP had nominated a mainstream candidate. (We’ll let you go through the 17 contestants and decide which ones might have been able to unite the party, run a solid campaign, and win.) Trump is neither mainstream nor conducting a campaign that is anything close technologically and financially to the Clinton effort.

In our view, this is why — along with strong partisan polarization — the contest, while close, has had Clinton pretty consistently in the lead: Trump is underperforming the fundamentals and reducing the odds of a GOP win. In another era, say the 1960s through the 1980s, the 2016 contest might well have produced a Democratic landslide much as outlier candidates in 1964 (Barry Goldwater) and in 1972 (George McGovern) generated big swings to the other party. Yet dislike of Clinton and polarization have kept her margin to a few points, excepting the post-convention bounce period. Clinton also faces an unprecedented challenge: She is not simply seeking President Obama’s third term and, in a sense, being responsible for the Obama record (good and bad), but in a way she is also pursuing Bill Clinton’s third term, too. Never before has a party nominee been held accountable for two two-term presidents.

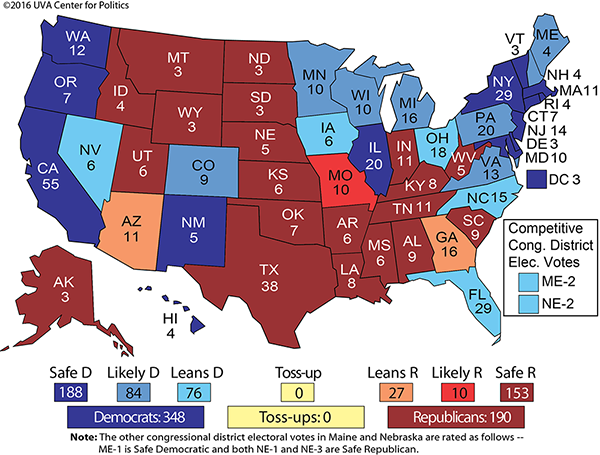

It may be that Clinton, if she does indeed win, will mimic one of Obama’s victory margins (four percentage points in 2012 or seven in 2008). Polarization was especially evident in Obama’s reelection contest. A four-point margin would be consistent with the Electoral College map the Crystal Ball has largely maintained since March: Her total of 348 electoral votes would place her performance in between Obama 2012 (332) and Obama 2008 (365). For Clinton to duplicate Obama’s 2008 broader sweep, Trump would probably have to collapse in the final weeks because of the accumulation of controversies and the lack of preparation in the ground game. If Clinton barely wins or Trump pulls an upset to rival 1948 (Harry Truman over Thomas Dewey), it probably means that Trump did something to improve voters’ perceptions of his qualifications for office — right now, a majority of the electorate does not believe he’s qualified — and Clinton, through a combination of mistakes, controversies, and Democratic apathy, can’t generate the kind of Democratic turnout she needs.

The challenge for the Democrats is to keep 2016 from becoming a change election, which it might have been without Trump (and could still become). Prospective Clinton voters will have to be reminded constantly why she believes Trump is unacceptable and why they have to swallow hard and vote for a candidate many are not enthused about. While our Electoral College ratings still show a Clinton victory, the polls have clearly gotten closer in recent weeks. Clinton is generally up about two-to-four points nationally in polling averages (based on RealClearPolitics and HuffPost Pollster), considerably tighter than the lofty eight-point lead she enjoyed in both averages about a month ago, when she was still basking in a post-convention glow and Trump was making mistake after mistake. In the lead-up to Labor Day, Clinton faced several questions about her emails and the Clinton Foundation, and Trump’s coverage became less negative by comparison.

Now Clinton is getting questions about her health (or, more appropriately, questions about how transparent she is being about her health) and Trump has succeeded, at the moment, in making the election less about him than about her. As former Obama speechwriter Jon Favreau observed, the race tends to get tighter when Clinton gets more attention and widens out to a bigger Clinton lead when Trump gets more attention, with an exception being the Democratic convention, which was essentially a big campaign ad for Clinton. This makes sense, particularly when the public views both candidates so poorly and coverage often focuses on their negatives (Trump’s lack of qualification for office and controversial statements versus Clinton’s lack of transparency and ethical challenges).

Generally, when the campaign has been more about Trump, he has suffered, and when it’s been more about Clinton, she has suffered. Gallup has been asking Americans if they have heard or seen anything about Clinton and/or Trump in “the last day or two,” which allows us to get a rough feel for which candidate is getting more attention on a given day. Over the period of July 5 to Sept. 13, there’s a weak negative correlation (-.29) between Trump’s polling margin in the HuffPost Pollster average and the margin between what percentage of respondents say they’ve heard about Trump minus the percentage who say they’ve heard about Clinton. That is, there appears to be at least a little bit of an inverse relationship between the relative level of coverage of Trump on the campaign trail and his polling margin. The more coverage, the worse his margin is, and vice versa. This correlation is stronger (-.49) over the past month (Aug. 13 to Sept. 13), moving beyond the convention period.

What’s problematic for Trump is that while we’ve seen this race yo-yo quite a bit over the past several months, it generally moves from a big Clinton lead to a small Clinton lead (where we are now). What we have not seen in polling is a period where Trump takes a consistent lead nationally and in a significant number of state-level polls. The key question of the moment is whether the race is clearly trending in Trump’s direction, and he soon will start to take consistent leads, or whether Clinton will reassert herself. Or, if this is just where the race will stay until Election Day, with Clinton holding a small edge.

Beyond the polls, there are other factors that will keep the Clinton campaign awake at night.

One is the fundamentals, particularly the seeming penalty that the president’s party pays for holding the White House for more than two terms, as we discussed above.

And then there is also the diversity and party makeup of the electorate. There’s a real possibility that it will not be as friendly to Democrats as the 2008 and 2012 versions.

Over the past several election cycles, the electorate has become more and more racially diverse, reflecting changes in the broader public. In 1996, 85% of registered voters were non-Hispanic white; now, just 70% are. This is according to the Pew Research Center, which just released an excellent new report on the composition of the two parties heading into this election. In 2012, Pew found that 73% of registered voters were white, so they’ve found the potential electorate getting more diverse over the last four years. So it is likely that the 2016 electorate will be at least as diverse as 2012 (28% nonwhite, according to exit polls) and potentially a couple of points more nonwhite.

But what if it isn’t?

It’s not impossible to imagine a small sag in African-American turnout now that Barack Obama is leaving the scene, and Clinton appears to be failing to motivate the youngest voters, who are very pro-Obama and do not like Trump but who also might vote third-party, as FiveThirtyEight’s Harry Enten found using SurveyMonkey research. The youngest generation is also the most diverse, and perhaps their turnout just isn’t quite as strong as it was four or eight years ago.

Trump does not benefit from growth in the nonwhite vote because our reading of the polls suggests that at best he’ll match Mitt Romney’s paltry 20% or so of the combined nonwhite vote, and he could easily end up doing worse. While a number of polls have shown Trump doing better than Romney with Hispanics, these voters can be difficult for pollsters to reach. Latino Decisions, a solid firm that contacts Hispanic voters in both English and Spanish, recently released a raft of national and swing-state polling that shows Trump lagging Romney among Hispanics.

Comparing 2012 polling data from three key battleground states — Colorado, Florida, and Nevada — to state exit polls that year provides some evidence for the underestimation of Democratic performance among Latino voters. Of the 21 polls with crosstab data from those three states completed between the final Obama-Romney debate on Oct. 22 and Election Day, 17 understated Obama’s margin among Hispanics compared to what each state’s exit poll found on Election Day. Now, some of that error was surely due to small Latino/Hispanic subsamples (though these were the swing states with the largest shares of such voters), and it’s always wise to remember that exit polls aren’t handed down by infallible polling gods — they too are polls, after all. Still, two-thirds of those surveys in Colorado, Florida, and Nevada missed the exit poll’s presidential margin (Obama’s percentage minus Romney’s) by at least 12 points, and nine undershot by 20 or more. It’s quite possible this could happen again, though the turnout challenge remains for Clinton, and if the nonwhite portion of the electorate sags, Trump could benefit.

One big challenge for Trump in this regard is that Clinton should have an advertising and ground game advantage. But it also may be that Clinton’s younger, more diverse base needs more cajoling to come out. There have been a number of recent state and national polls that have shown Trump doing better with likely voters than the larger universe of registered voters, which is in some ways a measure of enthusiasm (Republicans in general often do better after the LV screen is applied). Some of the gaps right now are large — a much-commented-upon national CNN poll that showed Trump leading by two points actually had Clinton up three among registered voters.

That leads to another question. What will the party ID makeup of the electorate be? In all likelihood, it will be more Democratic than Republican, because it usually is and that’s what the bulk of polling indicates, but the margin matters.

One of the most common polling complaints we hear is that the samples don’t accurately reflect what some people believe will be the partisan identification of the electorate. This charge led to the “unskewing” movement in 2012, when some Republicans took polls and changed the party ID in the Republican direction because they thought Republicans would make up a much bigger share of the electorate in 2012 than 2008 (they were wrong). Democrats picked at polls they didn’t like in 2014, and experts of all stripes found flaws with the many primary polls showing Trump leading in the primary (as it turned out most of the polls were right).

In the last two presidential elections, the electorate was 39% Democratic, 32% Republican, and 29% independent (2008) and 38% Democratic, 32% Republican, and 29% independent (2012). This is based on what voters tell exit pollsters, not what their formal party ID might be in states where voters register by party. In the Roper Center’s archive of national exit poll results, which dates back to 1976, the Republicans have never had a party ID advantage in a presidential election — the closest they came was a tie in George W. Bush’s close 2004 reelection victory. Republican party ID strength has since waned as conservatives have become disenchanted with their own party’s leadership, but just because a number of one-time Republicans consider themselves independents doesn’t mean that those voters truly swing from one party to the other. Most of the “independents” are hidden partisans — the Pew study found that the real party ID of registered voters is 48% Democratic or leaning Democratic and 44% Republican or leaning Republican, leaving just 8% of voters as true independents. This mirrors other polls and studies that show true independents as just a small portion of the electorate.

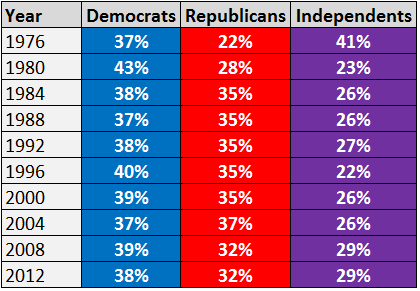

Table 1: Party identification in presidential elections according to exit polls

Source: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research

According to an average of national polls at HuffPost Pollster, this year’s electorate appears to largely mirror the electorate of 2008 and 2012 — it lists 36% of voters as Democrats, 30% as Republicans, and 32% as independents.

It stands to reason, based on the weight of polling evidence and history, that exit polls will show more Democrats in the electorate than Republicans, although keep in mind that the independent group could be more Republican-leaning than truly independent (the 2012 exit poll showed Romney won that group 50%-45%). But what will the actual number be? If the electorate is indeed D +5 or D +6, that should be sufficient for Clinton, and she could probably survive a narrower Democratic margin, but not too narrow.

But might the electorate actually be more Republican? Some polls are showing it. A Bloomberg poll of Ohio on Wednesday, conducted by the respected pollster J. Ann Selzer (mostly known for her Iowa polls), showed Trump up five points in Ohio and an electorate of R +7, much more Republican than Ohio in 2008 and 2012 (D +7-8 or so in both) but not in 2004 (which was R +5). Another Ohio poll, released late Wednesday by CNN, also showed a five-point Trump lead in Ohio with a party ID of R +1. These were Trump’s best polls of the whole cycle in Ohio.

If the electorate does end up leaning Republican, it’s of course good news for Trump. That’s because despite some anecdotal evidence to the contrary, we’re seeing a fairly high degree of party unity in this election. Given trends in American politics toward more partisanship and party polarization, this shouldn’t necessarily come as a shock.

Again according to HuffPost Pollster’s collection of two-way national polls, Clinton leads 84%-7% among Democrats, and Trump leads 83%-7% among Republicans (almost identical). Independents split 37%-35% for Trump. In the four-way contest, Clinton leads 81%-6% among Democrats, with 4% going to Libertarian Gary Johnson and another 3% going to “other” (HuffPost doesn’t name Green Party candidate Jill Stein, but that’s basically who is represented by “other”). Trump leads among Republicans 80%-6% with Johnson at 6% and other at 2%. Independents are tied 34%-34%, with 13% going to Johnson and 7% going to other. Total undecideds in the two and four-ways make up about 6%-7%.

We generally think that it’s hard for a candidate to win if he or she is short of 90% party unity, and Clinton and Trump both are. But we should see a fair amount of third-party voting this year — potentially close to 10% or the total vote — which lowers the amount of party unity that either candidate is likely to achieve.

Trump vs. Fortress Obama

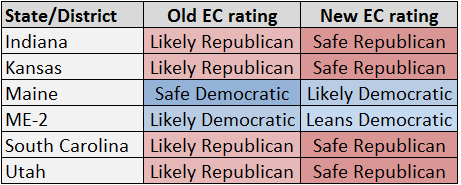

Trump’s improved position among Republicans and overall should at the very least allow him to solidify some typically reliable Republican states. While there have occasionally been close polls in Indiana, Kansas, South Carolina, and Utah, we just can’t imagine them voting for Clinton in anything other than a blowout election, and this one appears as though it will be relatively close. All four of these states move from Likely Republican to Safe Republican.

We’re also pushing Maine’s Second Congressional district from Likely Democratic to Leans Democratic. While we still see Clinton as a favorite to capture that single electoral vote — Nebraska and Maine both award some of their electoral votes by congressional district — it is a big, rural, blue-collar white district where Trump probably will outperform Romney. In fact, this rating may be generous to Clinton: A couple of recent polls of Maine have shown Trump leading in the district, although that would be a major shift in a district that President Obama carried by nine points. Still, this one could be headed to Leans Republican soon. And Maine itself goes from Safe Democratic to Likely Democratic, although it, like states such as Minnesota and Michigan that are also in the Likely Democratic column, seems very unlikely to actually flip even if Trump does win ME-2.

Map 1: Crystal Ball Electoral College ratings

Table 2: Crystal Ball Electoral College ratings changes

Now, we know what many of you are thinking — in fact, we’ve gotten plenty of emails expressing the same thought: How could the Crystal Ball still have Clinton at 348 electoral votes when she is only up by a small amount nationally? Hasn’t Trump done enough to flip at least one or more of the Leans Democratic states?

As of yet, he hasn’t. It is true that, if we were using the Toss-up rating (we are trying to hold off on that this year, in what could be a mistaken stroke of courage), then several states could probably be classified as such. Iowa, for instance, appears to be Trump’s best opportunity to win a state that Obama carried twice: The GOP establishment there, led by long-time Gov. Terry Branstad (R), is with him completely, and the state’s demographics are favorable to Trump. Iowa has a high percentage of non-college educated whites, and it is very white overall, two attributes that are helpful to Trump. Iowa also is more evangelical than many other Midwest states, which is helpful to Republicans more broadly, although Democrats have been able to hold the line there in recent presidential elections. If Trump really is flipping a fair number of typically Democratic blue collar voters, this would be a place we would see it.

Florida and Ohio, two big swing states that are must-wins for Republicans, are both very close. Trump now appears to have a small lead in Ohio, at least in the public polls, and perhaps in Florida, too, although we question the ability of public pollsters to get an accurate read on the true voting intentions of the state’s sizable Hispanic population, as described above. The same can be said for Nevada, another state that has been close in the polls. And North Carolina appears close, although many Republicans seem pessimistic about winning it. The Tar Heel State is another must-win for Trump, in all likelihood — he can afford no defections from Mitt Romney’s 206-electoral vote base.

Think about it this way: Clinton is running for President Obama’s third term, and she is not only defending his policies and record — she’s also defending his Electoral College fortress, if you will. There are 359 electoral votes worth of states (and Nebraska’s Second District) that voted for Obama at least once. Indiana, which Obama carried in a fluke in 2008, is already gone, which knocks Clinton’s total down to 348, where we have her right now. The fortress’s outer ring of defenses — the Leans Democratic states — is made up of Florida (29 electoral votes), Iowa (6), Nevada (6), North Carolina (15), Ohio (18) and two electoral votes from congressional districts in Maine and Nebraska. If Trump can break through in all of those places, he gets to 266 — four short of the majority he needs. He would need one other state, coming from the Likely Democratic column — places like Colorado, Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin. Trump is losing in those six states by an average of six points in the RealClearPolitics polling average, and Clinton has led 109 of 119 polls conducted in those states, combined, since last summer (Trump led just four, and there were six ties).

Trump has unquestionably made progress, but he’s yet to definitively take a lead in any state that voted for Obama outside of Indiana. He has a lot of work to do if he’s to breach Fortress Obama, let alone capture it. But for the Clinton campaign, these must be nervous times. The Democratic electorate does not seem particularly motivated right now — particularly the youngest voters, who can be hard to turn out anyway and who might disproportionately opt for third party candidates — which may amplify the importance of the first debate as a way for Clinton to try to rebuild her once-big lead. Or further fritter it away.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.