How Long Is Romney's Road To The Nomination?

A Commentary By Larry J. Sabato, Kyle Kondik and Geoffrey Skelley

The moon over Miami was a blue moon for Newt, a bad moon rising for Gingrich. This moon’s shine was all for Mitt Romney, illuminating a moon river that seems set to eventually carry Romney to the Republican presidential nomination.

But how fast is "eventually?" In this roller coaster race, no one should pretend to know the end point of the ride. There are some powerful examples of candidates who started losing with some frequency once their nominations seemed all but assured.

For example, President Gerald Ford looked like he had vanquished the challenge from Ronald Reagan once he had won the Iowa caucuses and primaries in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Vermont, Florida and Illinois. Then came March 23 and Reagan’s surprise victory in North Carolina, which started a see-saw battle that led all the way to the floor of the 1976 Kansas City convention.

Four years later, President Jimmy Carter thought he had iced Ted Kennedy after winning the Iowa caucuses and then primaries in New Hampshire, Vermont, Alabama, Florida, Georgia and Illinois. (In that stretch, the only primary Kennedy won was on March 4 in his home state of Massachusetts.) But on March 25, Kennedy shocked Carter by winning New York and Connecticut, and all told, Kennedy won 10 primaries and 37.1% of Democratic primary votes cast.

Can Newt be Romney’s Reagan or Kennedy? What will Ron Paul’s effect be, particularly in upcoming caucuses? And what of Rick Santorum, the forgotten man? He got more votes in Florida than Paul, after all.

First, let’s take a quick look back at why Florida turned out the way it did. After a bad week and a half in South Carolina, Romney responded with a good week and a half in Florida, particularly in the two debates held last week. Romney had perhaps his best moment of the entire campaign season when, last Thursday, he castigated Gingrich for what critics might describe as his early primary state “pork politicking” -- such as deepening the port of Charleston or, in an appeal to Florida’s space industry (that turned a bit comical), his proposal to establish a moon colony that could eventually seek statehood. Meanwhile, Gingrich fell flat in the final debate before the primary, even whiffing on his favorite technique: attacking the moderator. This time, Wolf Blitzer, unlike his CNN colleague John King in a South Carolina debate, didn’t walk right into the Gingrich haymaker.

Romney also brought his massive organization and fundraising advantages to bear, which made a big difference in Florida. With more than 600,000 ballots cast by absentee or early voting, Romney’s was the only campaign to organize the effort in a substantial way. This paid off, and he cleaned up among the early vote. Romney and his Super PAC outspent Gingrich and his PAC by about five to one, and Romney’s TV ads were relentlessly negative. Romney also called in his chits among establishment Republicans -- Bob Dole and a bevy of current and former GOP officeholders -- to condemn Gingrich in the strongest possible terms. South Carolina convinced Republican leaders that Gingrich could win the nomination and, in their view, sink the party’s chances in November. Oddly, Newt’s big Palmetto victory was the yin that produced the yang of Romney’s triumph in Florida.

Why does the Florida victory matter so much more than the first three contests? For one thing, the Sunshine State has 29 very independent electoral votes; the previous contests in Iowa (six electoral votes), New Hampshire (four) and South Carolina (nine) had 19 combined, with the third contest being guaranteed Republican for any GOP nominee. And make no mistake: Compared to South Carolina, Florida was a naturally more hospitable place for Romney, seen as the more moderate-conservative candidate. According to exit polls, two in five voters were evangelical or born-again Christians in Florida, much less than the more than three in five in South Carolina.

Gingrich’s decisive defeat should quiet rumblings of a late entrant, although as our Rhodes Cook argued in December, there’s still time for a candidate to get on the ballot in several late, important contests, such as primaries in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California. But the deadline for entry, in some cases, will come and go as early as next week. The Florida result will only hasten the march of top Republicans, officially or unofficially, into the Romney camp. Republicans may not love Romney, but most of them don’t fear him at the top of their ticket. As a result, the existing field looks more set than ever.

Given Romney’s long lead in money and organization, it is somewhere between very difficult and impossible for Gingrich to seize the actual nomination. But can Gingrich cause headaches -- maybe even migraines -- for Romney by winning more primaries? Definitely.

Whatever Romney’s problems, February is not a good month for Gingrich. The next event is in Nevada, where four years ago Republican caucus-goers -- more than a quarter of them Mormon -- cast a majority of their votes for Romney (51%). Expect Romney to do well there again, and it’s even possible that Ron Paul will push Gingrich into third place. Beyond Nevada are more caucuses in Maine (where Paul has been spending a good deal of time), Colorado and Minnesota. Any caucus gives an opening to Paul to exceed expectations. Afterwards, there is a three-week lull before the primary season returns with big contests in Michigan and Arizona.

Rick Santorum, who is appealing to some of the same voters as Gingrich, faces some of the same problems as Newt. And Santorum’s moment appears to have come and gone; he has done poorly since Iowa. Were Santorum to leave the race, the battle for the nomination could get somewhat more interesting -- although polling suggests that Santorum’s backers are not monolithic and would split between Romney and Gingrich. When the money runs out, candidates usually depart the race, but Gingrich is a good bet to hang in, in no small part because of his rich friends in Nevada, the Adelsons, who have already given $10 million to support his cause. Paul could outlast his non-Romney rivals, but his low ceiling in most non-caucus states prevents his nomination.

None of the February contests are good for Gingrich. Caucuses, by their very nature, reward long, detailed planning and considerable resources to gin up turnout. Translation: They are tailor-made for Romney and Paul. Additionally, from what we know about these states from 2008 exit polling, none of them are likely to have the heavy percentage of evangelical voters that Iowa or South Carolina had (about 60% or so apiece), which means they will be less conservative and more amenable to Romney or Paul.

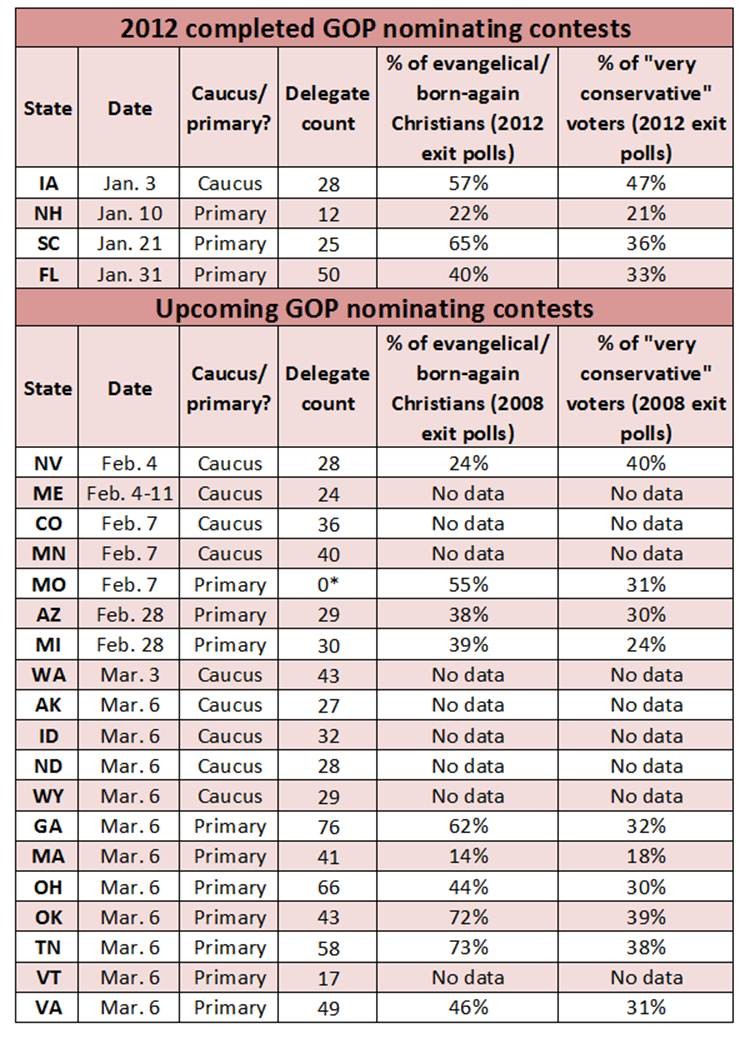

Chart 1 shows the nomination contest calendar from now through Super Tuesday. Keep an eye on the Washington State caucus, which is the last event before Super Tuesday. Washington has the most delegates of any upcoming contest prior to Super Tuesday, and Romney and Paul are already organizing there.

Chart 1: After Florida – Upcoming GOP nominating contests through Super Tuesday

Notes: Exit/entrance poll data comes from CNN. "No data" indicates that there was no exit/entrance polling information from CNN. Delegate counts gathered from Frontloading HQ.

*The Missouri primary is non-binding and Newt Gingrich did not qualify for the ballot there. The GOP will hold a caucus on March 17 to determine its delegates.

It is on Super Tuesday, March 6, when Gingrich might be able to get back into a decent position to win somewhere. With heavily conservative, evangelical electorates, Southern states Georgia, Oklahoma and Tennessee might be receptive to the Gingrich candidacy. After all, Newt is running as the closest thing to a traditional Southern Republican. Alabama and Mississippi vote the following week, on March 13. Virginia, too, could have been fertile ground for Gingrich, but thanks to his failure to make the ballot, we’ll never know. (Primary voters in the Old Dominion can only vote for Romney or Paul on Super Tuesday. There are no write-ins.)

By the way, this Super Tuesday is less Man of Steel than Clark Kent. In 2008, there were 21 Republican contests that awarded more than half of the total delegates to the Republican convention. This Super Tuesday, there are only 11 contests that award just about a fifth of the total delegates to the convention.

One major question in determining the effective length of this race is how long the press wants to cover it. Perhaps the best piece of news for Romney now is that, after seven debates in January, only one is scheduled in February (in Arizona on Feb. 22). The other candidates would surely like more, but Romney -- who apparently considered skipping last week’s debates in Florida before realizing that he couldn’t -- is unlikely to agree to more. How the press assesses whether Romney is the prohibitive front-runner -- or even the presumptive nominee -- is a significant factor in determining whether he actually is the prohibitive front-runner or presumptive nominee. As it is, Romney only has about 7% of the 1,144 or so delegates he needs to secure the nomination. But perception in these early contests is always more important than reality.

When it’s all said and done, we believe that Romney will be giving the acceptance address in Tampa come late August. But it matters enormously whether he wins pretty or limps home ugly. A much tougher opponent remains for Romney when the harvest moon shines.

Larry J. Sabato is the director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

See Other Commentary by Larry Sabato

Kyle Kondik is the House Editor at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

See other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik .

See Other Political Commentary

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.