10 Factors That Will Determine the Next President

A Commentary By Larry J. Sabato, Kyle Kondik and Geoffrey Skelley

Here’s a thought experiment: What if Republicans nominated the 2012 version of Mitt Romney — same fundraising, same baggage, same everything — at their 2016 convention? What sort of odds would that candidate have in 2016?

We suspect the candidate would be a small favorite at the start of the campaign. He would be running against a Democrat who lacked the power of incumbency, and he would be competing in an environment where the public was ready for a change: The most recent NBC/Wall Street Journal poll showed that about three-quarters of those surveyed wanted the next president to take a different approach to governing than President Obama, similar to how the public felt about how George W. Bush’s successor should act at a similar point in the 2008 campaign. It’s hard to precisely quantify, but there’s a generic desire for change that hampers a party the longer it stays in the White House. To satisfy that general feeling, a generic Republican might do the trick, which is why we cite Romney circa 2012 as an example of what could/should be enough to win the White House: A candidate who is largely average could flip a few percentage points of the national vote from the 2012 results, which is all it will take for the Republicans to win.

However, it’s quite unclear that the Republicans will produce a candidate of even the quality of Romney. After 2012, the party took a hard look at its inadequacies, producing a report that suggested the party needed to do more to reach out to nonwhite voters. Donald Trump, the GOP’s current polling leader, is not helping on that front. The Republican leadership is worried.

What follows is an exploration of 10 factors that will probably determine the White House winner next year. Some of these — many of them, in fact — suggest that the GOP should be seen as a narrow favorite. But a few factors, combined with the live possibility that the next Republican nominee will make Mitt Romney look like Ronald Reagan, indicate to us that, as we turn the page from 2015 to 2016, that the 2016 general election is still a coin flip.

1. THE CANDIDATES

It’s easy to forget, in this age of strong party polarization among voters, that the strengths and weaknesses of the presidential candidates are critical factors in an election. Partisans may not switch sides very often, but the intensity of support for their nominee affects donations, volunteer activities, and even turnout.

No one can know for sure how the candidates will look next fall. The first hurdle for Republicans will be reunification, and that may not prove an easy task. The party’s deep fissures are on prominent display right now. Given his high negatives, Trump might have a harder time bringing Republicans together than his competitors would. Either an independent bid by Trump, or in the unlikely event of a Trump nomination, an independent bid by a “real Republican” (a traditional mainstream candidate) cannot be ruled out at this point. Nor could a candidate as conservative and controversial as Ted Cruz count on the enthusiastic backing of the GOP establishment. Intense dislike of Obama and Hillary Clinton will help the GOP, and some contenders are better positioned than others to put the party back together. Nonetheless, party diplomats will probably have their hands full through November.

As for Clinton, party reunification will be relatively straightforward: Sanders supporters aren’t going to sit out the election or defect in any significant numbers. Clinton’s image is something else again. Voter views about her are so fixed after a quarter-century in the spotlight that she’ll have a difficult time projecting a new Hillary. On the one hand, few longtime Clinton observers seriously question her intelligence or grasp of policy. On the other, Clinton isn’t an exciting campaigner, and many people — and not just Republicans — don’t much like or trust her. The gender card may be her best bet to motivate partisans, along with liberal fear of what Republicans may do on social issues if they control both the White House and Congress.

Both party nominees may be flawed enough to look for issues that will make the election bigger than themselves. The most obvious one — sure to be used extensively by both sides — is the Supreme Court, which is almost as politically polarized as the elective branches. Given the ages of some current justices, it is very believable that the next president will reshape the court.

One other thing: While it seems likely that nominating Trump would be a political loser for Republicans, let’s not underestimate his potential to dramatically recalibrate his pitch for a general electorate. His established proposals (and outrageous statements) would remain, but if anyone could pull off a massive rebranding job, it might be The Donald.

2. THE PRESIDENT’S JOB APPROVAL

President Obama is not on the ballot, but he looms over the race. His national standing has remained very consistent — some would say stagnant — throughout much of his presidency. Throughout 2015, Obama’s approval has generally been around 45%, with a little bit of variation. It seems reasonable to expect that he will be around the same point next year, unless further domestic terrorism or other developments send his ratings tumbling. According to Gallup, Obama has averaged a middling 47% approval throughout his presidency, and as we found earlier this year, his approval has been the steadiest in modern history.

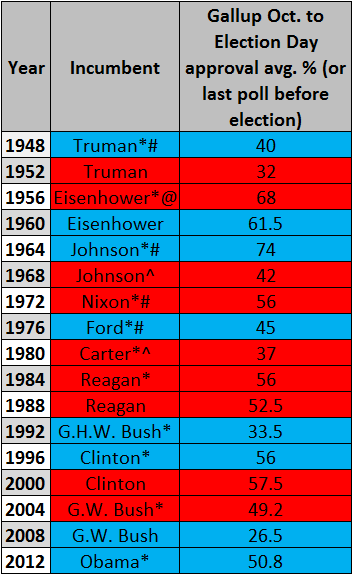

Postwar history suggests that when a president has weak approval, his party pays a price in the next election. Harry Truman (1952), Lyndon Johnson (1968), Gerald Ford (1976), Jimmy Carter (1980), George H.W. Bush (1992), and George W. Bush (2008) all had mediocre-to-poor approval ratings, and the opposing party won all of those elections (defeating incumbents Ford, Carter, and H.W. Bush, and winning open-seat races in the others). Meanwhile, the strong approval ratings of Dwight Eisenhower (1960) and Bill Clinton (2000) couldn’t save their would-be successors, Vice Presidents Richard Nixon and Al Gore. Both lost excruciatingly close elections. Some of these approval ratings are from months before the election and don’t necessarily reflect where the incumbent’s approval was on Election Day — Truman, for example, was at 40% in late June 1948, but his approval was likely higher by November, when he won an upset victory.

Table 1: Approval of sitting president at time of election, 1948-2012

Notes: *Signifies an incumbent seeking reelection. The years are shaded by the color of the party that won the election (blue for Democrats, red for Republicans). These symbols indicate the polling month of the approval rating if not October or November: #June, @August, ^September.

Source: Gallup Presidential Job Approval Center

There’s one other factor to consider, though. It’s possible that in a partisan age, job approval doesn’t mean what it once did. Just think back to the 2014 midterm. Then-Gov. Pat Quinn (D-IL) was at about 30% approval, but he only lost by four percentage points. Gov. Sam Brownback (R) and Sen. Pat Roberts (R) of Kansas had approval ratings in the mid-30s, but both won reelection. Granted, both of those states have strong partisan tilts (Illinois is Democratic, Kansas is Republican), and these were state-level races in a midterm year, but it’s possible that low approvals aren’t as much of a drag as they might once have been. Perhaps Obama’s approval will drop below the mid-40s, but Clinton could win if the Republicans produce a poor nominee. The other thing is that, with the history of presidential approval ratings cited above, we do not have a huge sample size. There isn’t a hard-and-fast rule here, but there is a reason that Clinton, so far, is generally staying close to the president. Presenting a united Democratic front, and seeing Obama have a successful final year in office, can only be good for her chances. Plus, if Obama tanks, so probably do Clinton’s chances.

3. THE STATE OF THE ECONOMY

As we noted earlier this year, there’s been on average about one recession every five years since 1901, and the last recession ended in June 2009. That doesn’t mean there will be a recession before the next election, but if there is, there’s every reason to expect that it would be a drag on the incumbent president’s party (the Democrats).

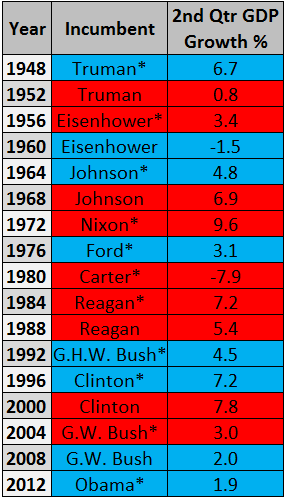

Table 2 shows second-quarter GDP growth in election years dating back to 1948. We picked second quarter GDP because it is an important variable in Crystal Ball Senior Columnist Alan I. Abramowitz’s Time for Change presidential election model, which has a strong history of predicting the national two-party vote in presidential elections.

Table 2: Second-quarter GDP growth in presidential election years, 1948-2012

Notes: *Signifies an incumbent seeking reelection. The years are shaded by the color of the party that won the election (blue for Democrats, red for Republicans)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

The GDP growth totals complement the approval numbers listed above. Perhaps a reason why Nixon couldn’t capitalize on Ike’s high approval was an economy that suffered a significant slowdown in the middle of the year. Carter was doomed by many factors in 1980, including a weak economy; George W. Bush (2004) and Barack Obama (2012) won competitive reelections with middling approval ratings and mediocre growth.

One related factor sometimes cited by Republicans as evidence of their bright prospects next year is right direction/wrong track polling, which currently features a highly negative split. According to both major poll aggregators, only about a quarter of those polled believe the country is headed in the “right direction,” while about two-thirds believe it’s on the “wrong track.” That is a very poor number, although the Daily Beast’s Dean Obeidallah found that Americans almost always say the country is on the wrong track, going back more than four decades when pollsters first began to ask the question. When Obama was reelected, the right direction/wrong track gap was about -15 points — significantly better than now but also weak. This is a broader measurement than economic growth and, while it is persistently negative, it may be another measure that merits monitoring.

4. FOREIGN POLICY AND TERRORISM

Democrats are attacking Sen. Rob Portman (R-OH) for recent comments suggesting that a focus on foreign policy and terrorism would be good, politically, for the Republican Party. “We’re in a period in our country’s history sadly where we have a threat from abroad again,” Portman said. “And, y’know, people tend to look to Republicans to help protect the country.” He’s probably right. Since 9/11, the public has generally seen Republicans as the stronger party in dealing with terrorism. Recent issue polling has also suggested that Americans are increasingly concerned about terrorism, no shock given the twin horrors of Paris and San Bernardino. What’s important now is not guaranteed to be important in fall 2016, but it will be a surprise if terrorism isn’t one of the top concerns at election time.

5. SOCIAL ISSUES

Some of the Democrats’ greatest and unlikeliest political triumphs in recent years came when Republicans led with their chins on social issues — just think about the many poor Republican Senate candidates in recent years who made out-of-the mainstream comments about abortion and other issues, comments that contributed to their losses. Democrats will surely try to paint the Republican nominee as too far right on certain issues, depending on the candidate. Against Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz, they would emphasize abortion (Rubio has suggested he opposes abortion without any exceptions, while Cruz backs fetal personhood, a position that has been defeated in ballot issues even in very conservative states). Against Donald Trump, it would be his alleged hostility to nonwhites. Just like Republicans on terrorism, Democrats believe that if the election is about issues such as abortion and immigration, and their opponent’s far right positions on these issues, they can make the GOP nominee unelectable.

6. RUNNING MATES

We’ll hear a thousand times in the next year that the last vice presidential running mate who made a decisive difference was Lyndon Johnson in the squeaker election of 1960, carrying Texas and some other Southern states that John F. Kennedy might have lost on his own. That’s true — a Johnson is a rarity, but then again, maybe we’re overdue for another LBJ. Many VP candidates have had some impact, though the effect, while minor, has often been negative and distracting, modern examples being Spiro Agnew (R, 1968), Thomas Eagleton (D, 1972 — Sargent Shriver ended up replacing him on the ballot), Geraldine Ferraro (D, 1984), Dan Quayle (R, 1988), and Sarah Palin (R, 2008).

In 2016, the potential exists on one or both sides to nominate a VP candidate who enhances the ticket and maybe even helps carry one of the few real swing states. It’s pointless to list Republican possibilities because we do not yet know the identity of the GOP presidential nominee. Privately, Republican leaders mention a “dream ticket” of Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida and Gov. John Kasich of Ohio, who together might deliver 47 swing-state electoral votes. At this early juncture, it might be better termed the “pipe dream” ticket.

Hillary Clinton’s VP choices are limited because of the wipeouts the Democrats have suffered at other levels in Obama’s two midterm elections. The most mentioned and logical possibilities are Sen. Tim Kaine of Virginia, Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio, and perhaps Gov. John Hickenlooper of Colorado. Should the Republicans put Rubio on their ticket in either position, then Clinton may want to pick one of the Castro brothers, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Julian Castro or U.S. Rep. Joaquín Castro of Texas, to solidify her standing with Hispanics.

The Democrats may not have a long list of possibilities, but they have one significant advantage in the 2016 Veepstakes: Theirs is the second convention next summer, so Clinton can make her decision after seeing what the GOP ticket looks like.

7. THE DWINDLING NUMBER OF SWING STATES

Abramowitz, our Crystal Ball colleague, often reminds us that we don’t really have national elections for president anymore.

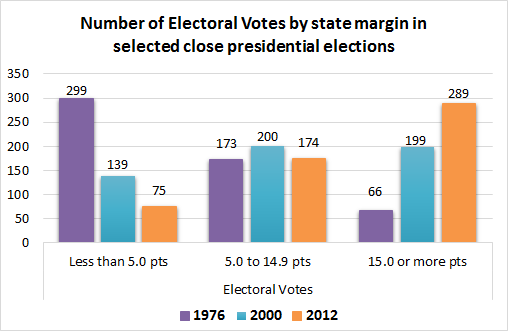

In the 1976 Jimmy Carter-Gerald Ford election, 20 states were decided by less than five percentage points, including every one of the most populous states (such as California, Illinois, New York, and Texas). Fast forward to the 2012 contest between Obama and Romney. It was within five percentage points in a mere four states, and a blowout for one candidate or the other in a large majority of the states. Chart 1 shows the decline in the number of electoral votes contained in truly competitive states in three recent close elections: 1976, 2000, and 2012:

Chart 1: Number of electoral votes by state margin in selected close presidential elections

Sure, if Donald Trump is the GOP nominee (or possibly a few others in the current lineup), the country might temporarily break out of its hardened Electoral College map. However, we’d bet that any Republican — even Trump — would fare far better than Barry Goldwater did in 1964. Our polarization is such that the GOP nominee will probably start around (at a minimum) John McCain’s 2008 percentage, 46%, not Goldwater’s 38%. (This assumes there are no 2016 third-party candidates that complicate the picture.)

Without a major independent ticket and assuming a close election, there’s a high probability that about 40 states can effectively be called by Labor Day. The campaigning will thus concentrate on the closest swing states: Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Virginia. Republicans will make some effort yet again to win over Pennsylvania and Wisconsin (and possibly a few others) while Democrats will try to replicate Obama’s 2008 win in North Carolina. Maybe the VP nominees will add a state or two to the competitive category.

Still, if you live in dark red or deep blue America, plan on watching the White House contest from afar.

8. SCANDAL

You just never know when a scandal will strike, or whether it will matter, or which candidate will suffer disproportionately.

Ever since Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign, when the future president survived enough incoming scandal fire to sink a battleship, it’s been less likely that private-life revelations — or most anything else — would automatically eliminate a candidate. Perhaps in the anything-goes modern era of press coverage and widespread social media rumor-mongering, voters have become hardened to scandals. We have a low opinion of politicians, we expect it, and we shrug it off.

It’s pointless, and irresponsible, to speculate about what lies in store next fall. Yet with four national candidates on the two major-party tickets (plus possible independents and third-party pairs), there are bound to be several scandals or scandal-ettes that will dot the calendar.

Do they matter? We’ve already seen this year that Hillary Clinton’s use of a private server weakened her, and it’s not over yet. Scandal and controversy about Donald Trump apparently have had no effect on his supporters. Small scandal bursts have been recorded above Marco Rubio, Bernie Sanders, Ben Carson, and others, with varying degrees of impact.

On the whole, scandal is probably a greater danger during the primary season, because there are alternatives available to jittery partisans. In the general election, except for a massive, fundamental expose, the party candidates are protected by party and polarization. Bigger factors and issues are likely to drive the election outcome.

A little spice, though, keeps everyone attentive.

9. AMERICA’S CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS

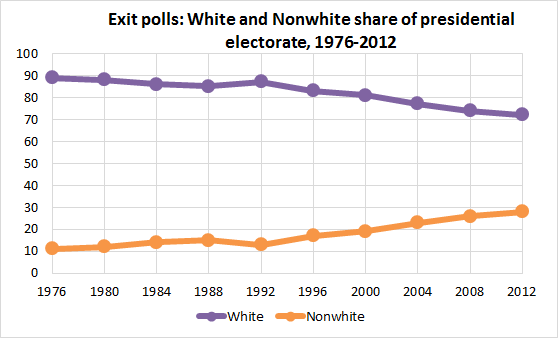

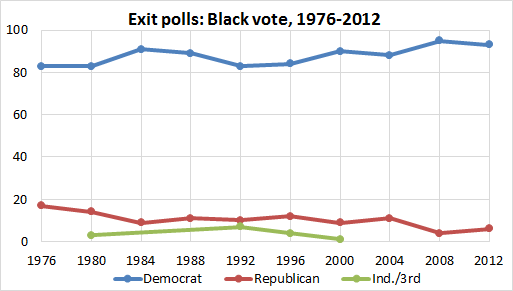

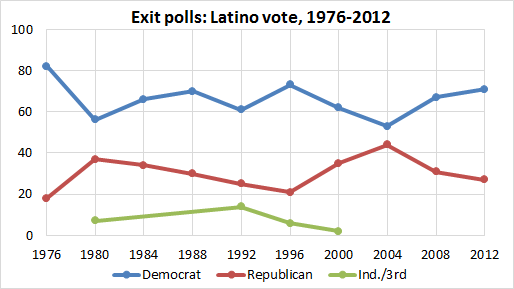

It’s quite possible that the most important data point on Nov. 8, 2016, will be the nonwhite share of the electorate. This assertion is based on two observations: First, that exit polls have shown nonwhites to be an increasingly large portion of the electorate; and second, that nonwhites backed Barack Obama at a higher than 80% rate in 2008 and 2012.

The nonwhite share of the electorate is likely to continue growing, as shown in Chart 2. In 1976, exit polls found that nonwhites made up 11% of voters; in 2012, that figure was 28%. Except for a blip in 1992, this trend has been continuous.

Chart 2: White and nonwhite share of the electorate, 1976-2012

Source: Roper Center

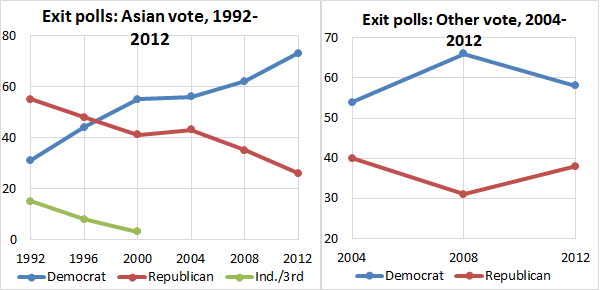

Minority voters are a key component of the Democrats’ “Coalition of the Ascendant” — nonwhites, Millennials, and highly-educated whites — which many Democrats believe gives them a natural edge in the 2016 presidential contest. Some Republican strategists worry that the GOP’s struggles with nonwhites will make it hard for the Republican nominee to win in 2016 (and beyond). After all, Mitt Romney won 59% of the white vote but lost nationally by about four percentage points. Still, can the Democratic nominee repeat Obama-levels of support among nonwhite voters? And if the GOP nominates Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz, could it reap at least some benefit from having a more diverse ticket? Obama gained a small boost among African Americans in 2008 and 2012 compared to Al Gore and John Kerry, so it’s not far-fetched to think Rubio or Cruz could do so, although blacks were already heavily Democratic. While Hispanics generally lean Democratic, their political identity isn’t as monolithic — Pew’s 2014 data showed 82% of Latinos tilting one way or the other (56%-26% Democratic), versus 91% of African Americans (80%-11% Democratic).

The Crystal Ball has previously highlighted that a uniform shift of three points in the 2012 result would have handed Romney 305 electoral votes and victory. Correspondingly, David Wasserman recently pointed out that a three-point swing toward Republicans among five major demographic groups from 2012 — with the same turnout levels — would result in a GOP win in 2016. At this very early point, most election fundamentals point to a competitive environment in 2016, so it’s certainly feasible that this kind of shift could happen, especially without an incumbent on the ballot. Turnout among different groups, discussed next, is also vital. But first, take a look at the exit polls for different demographic groups from 1976 to 2012.

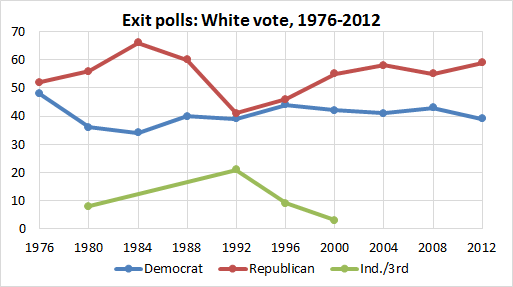

Charts 3, 4, 5, and 6: Presidential vote by different demographic groups, 1976-2012

Notes: Data available for Whites, Blacks, and Latinos from 1976 to 2012. Data for the Asian vote available from 1992 to 2012, “Other” available from 2004 to 2012. Independent and/or third-party vote only for leading non-major party candidate in respective year (1980: John Anderson; 1992 and 1996: Ross Perot; 2000: Ralph Nader).

Source: Roper Center

10. TURNOUT

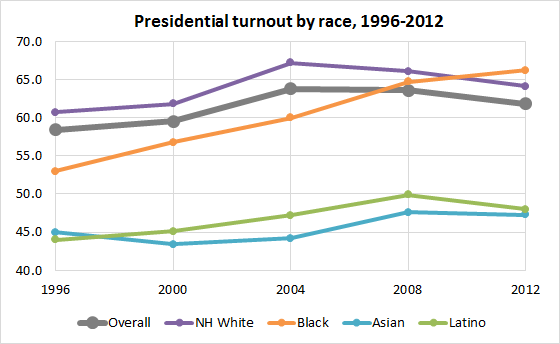

Without Obama’s name on the ballot, it’s an open question whether Democrats will be able to be repeat what they accomplished in 2008 and 2012. According to the Census Bureau’s postmortem on 2012 turnout, African Americans turned out at a higher rate than non-Hispanic white voters for the first time in terms of reported turnout of the citizen voting-age population (CVAP). As Obama was winning 95% (2008) and 93% (2012) of the black vote, based on the exit polls, the increased number of voters from this demographic group obviously buoyed his campaign. To some extent, overall turnout will probably remain relatively high in 2016, if the last few elections are any indication — going back to 2004, turnout has been above 60% of CVAP. Granted, these weighted estimates were based on self-reported voting, which usually sees over-reporting (by about 3.7 million votes in 2012). Still, these numbers are useful for analyzing turnout rates among different demographic groups, and the difference between actual turnout and reported turnout has been relatively small in the last three elections. Chart 7 shows the turnout levels by CVAP by racial and ethnic groups since 1996.

Chart 7: Presidential turnout by demographic group by citizen voting-age population percentage, 1996-2012

Note: Figures represent the percentage of the citizen voting-age population that reported voting

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey report

Sans Obama, turnout among parts of the Obama coalition, particularly African-American voters, could slide a bit. Considering that a three-point shift toward the GOP among major demographic groups would have resulted in a narrow Romney win in 2012 without lower turnout, reduced turnout among Democratic-leaning constituencies would only boost Republican chances. If the Republican nominee makes some inroads with minority voters while holding the line or even improving support from white voters, the GOP will be positioned to win. In other words, we can say that demographics are not necessarily destiny; as always, those who show up will decide the election, and projections of change in the electorate do not always materialize along consistent lines.

Larry J. Sabato is the director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

Geoffrey Skelley is the Associate Editor at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

See Other Political Commentary by Larry Sabato

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik

See Other Political Commentary by Geoffrey Skelley

See Other Political Commentary

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.