2022 Gubernatorial Races: A Baseline

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman

Aside from Maryland, no statehouses are initially favored to flip -- but surprises are surely coming.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— 38 states will see gubernatorial races over the next two years; Democrats currently hold 18 of the seats that will be contested while the GOP holds 20.

— Maryland, where popular Gov. Larry Hogan (R-MD) is term-limited, will be hard for Republicans to hold. With a Leans Democratic rating, the Crystal Ball expects a Democrat to flip the seat.

— We’re starting the cycle off with five Toss-ups: Arizona, Georgia, Kansas, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Not coincidentally, four of those gave President Biden very narrow margins last year.

— Democrats are clear favorites to retain governorships in three of the nation’s most populous states — California, Illinois, and New York — but they could be better-positioned in each.

— In the Senate, Sen. Roy Blunt’s (R-MO) retirement nudges that contest from Safe Republican to Likely Republican.

Sizing up 2022’s gubernatorial landscape

Midterm election cycles feature the lion’s share of the nation’s gubernatorial races, and there will be 38 gubernatorial elections over the next two years — New Jersey and Virginia in November, and the rest next year. We took a look at the 2021 races last week, and now we’ll dive into the 2022 races.

Just as in congressional elections, the president’s party often struggles in gubernatorial races. The president’s party has lost governorships in 16 of the 19 midterms since the end of World War II, and two of the three exceptions (1962 and 1998) were years where there was no net change. Only in 1986, Ronald Reagan’s second midterm, did the president’s party enjoy a gubernatorial net gain (eight seats) in the postwar era.

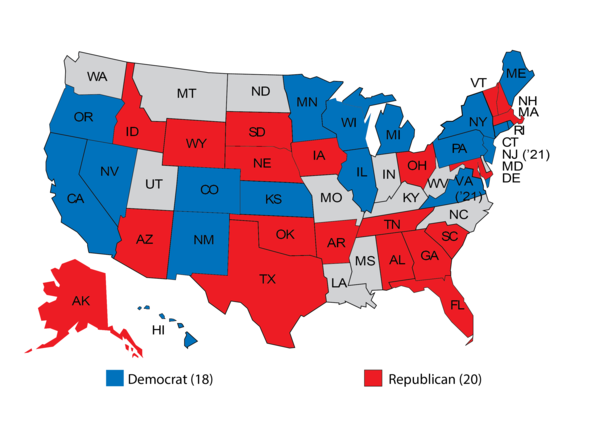

Overall, Republicans control 27 governorships and Democrats control 23. Of the 38 up this cycle, Republicans hold 20 and Democrats hold 18. The current party control of those governorships is shown in Map 1.

Map 1: Current party control of governorships being contested in 2021-2022

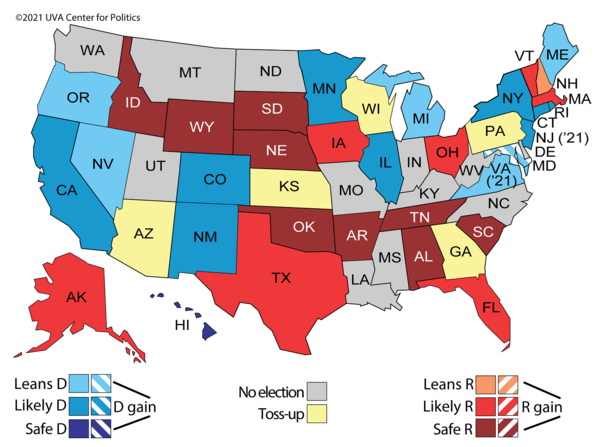

Our initial ratings for these races are shown in Map 2.

Map 2: Crystal Ball gubernatorial ratings

Compared to 2018, 2022 could be a cycle defined by greater stability in gubernatorial politics. Four years ago, only 20 races featured incumbents running for reelection. This time, only seven governors who were up in 2018 are term-limited, though others who are eligible to run again may decide not to. Still, this isn’t to say that there’s no potential for partisan turnover.

Maryland: A tough hold for the GOP without Hogan

We’ll start our initial sweep through the map with Maryland, which is the only state we see changing hands right off the bat. Now-outgoing Gov. Larry Hogan (R-MD) was one of 2014’s upset winners. That year, Hogan made fiscal restraint a centerpiece of his campaign and had the good fortune of running against then-Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown (D-MD) — Brown was widely criticized for his handling of the state’s Obamacare exchange. In 2018, against an underfunded Democratic challenger, Hogan rode out a national Democratic tide to become Maryland’s first Republican governor since 1954 to secure reelection.

Though Hogan, who has emerged as one of the most prominent voices in the anti-Trump faction of the GOP, was able to find success, he’ll likely have a tougher time trying to dictate his successor. Lt. Gov. Boyd Rutherford (R-MD) may be an attractive candidate, but his office might as well have an “abandon all hope ye who enter here” sign above it — Maryland voters have never elevated an incumbent lieutenant governor to the state’s top job. With Democrats in charge of the state’s redistricting process, the lone Republican in Maryland’s congressional delegation, Rep. Andy Harris (R, MD-1), may very well get a blue district. This may push Harris to consider running statewide, though he’s much more conservative than Hogan.

Of the few announced Democratic candidates, state Comptroller Peter Franchot leads the field. First elected to public office in 1986, Franchot has carved out a niche as something of a moderate Democrat who will take on his own party. From an electoral perspective, this approach seems a hit with voters: in 2018, he was reelected 72%-28%, the best showing for a statewide Democrat since 1990. Aside from Franchot, there are no shortage of Democrats who could run in this blue state, and we think any competent Democrat would be favored over a generic Republican. Hence, our Leans Democratic rating.

The Toss-ups

Perhaps not surprisingly, four of the closest states in the 2020 presidential election feature Toss-up gubernatorial races in our initial 2022 ratings. Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin were all states that Donald Trump carried in 2016, but each gave President Joe Biden pluralities last year. Digging further into that quartet, there’s a nice symmetry: two will see open seat contests this cycle while two feature incumbents who can run again.

In Arizona, Gov. Doug Ducey (R-AZ) is term-limited. While some governors have seen their approval ratings soar as the COVID-19 pandemic has lingered on, this has not been the case for Ducey — as Arizona has been hit particularly hard, his image has suffered. So in Arizona, the GOP could benefit from running a fresh face. Aside from Ducey, who led the state Republican ticket in 2018, first-term state Treasurer Kimberly Yee was the best-performing Republican that year. But in a primary, Yee may have competition from state Attorney General Mark Brnovich, who is term-limited in his current job. Unlike the past few midterms, Democrats are entering the cycle with a statewide bench in Arizona — specifically, Secretary of State Katie Hobbs has been mentioned as a candidate, though other Democrats may run.

After two impressive performances in the Keystone State, Gov. Tom Wolf (D-PA) can’t run for a third term. In 2014, Wolf, who had no prior experience in elected office, parlayed his background as a business executive into a winning campaign against then-Gov. Tom Corbett (R-PA). If Wolf’s image as a political outsider was part of his appeal, many state Democrats seem intent on replacing him with a more experienced politician. In Pennsylvania politics, it’s been a poorly kept secret that state Attorney General Josh Shapiro, who was just reelected last year, has his eye on the governorship.

While Pennsylvania elects its governor in midterm years, it elects a slate of three row offices — auditor, attorney general, and treasurer — in presidential years. Even as Trump carried the state in 2016, Democrats swept the three row offices. But, almost paradoxically, as Biden flipped Pennsylvania, the GOP picked up the auditor and treasurer posts. So aside from Wolf, Shapiro is now the only non-federal statewide Pennsylvania Democrat who’s been elected in their own right (Lt. Gov. John Fetterman, also a Democrat, was part of Wolf’s ticket in 2018 and is running for U.S. Senate). The Republican side is more open. Pennsylvania is unique this year in that it has open contests for both Senate and governor, so candidates may take some time to settle on which campaign seems more promising. Until Wolf’s 2014 victory, one rhythm was constant in state politics: beginning in 1954, Pennsylvania voters would put one party in control of the statehouse for two terms, then choose the other party for two terms. Could 2022 mark a return to form?

Wisconsin shouldn’t see an open seat contest in 2022, but, as usual, we expect the state to host a competitive race. In 2018, in their fourth attempt, Badger State Democrats finally defeated now-former Gov. Scott Walker (R-WI). But after taking office, Gov. Tony Evers (D-WI), a generally inoffensive Democrat who is expected to run again, has constantly battled with a hostile legislature. Though they’ve fought over several items, the COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated the fault lines between Evers and state Republicans. In the earlier months of the pandemic, legislative Republicans challenged a stay-at-home order that Evers issued — on a partisan vote, the GOP-friendly state Supreme Court sided against the governor. More recently, last month, Republicans, with their large majorities in the state legislature, repealed a mask mandate that Evers put into place.

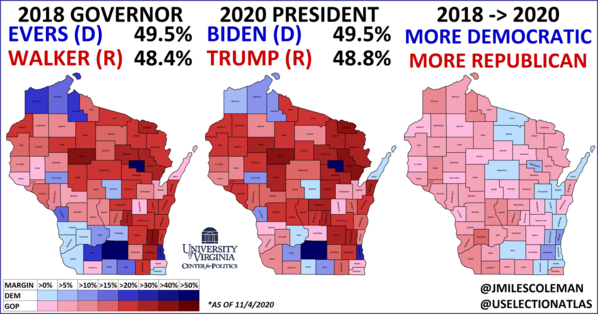

Former Rep. Sean Duffy (R, WI-7), who held down a rural district in the northern part of the state for much of the last decade, is sometimes mentioned as a gubernatorial candidate. Last week, Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI), who’s been noncommittal on his 2022 plans, suggested that he’s leaning towards retirement. The Senate race, without Johnson, would likely attract some ambitious Republicans, but in this sharply divided state, we have to imagine Republicans will find a quality recruit. In 2020, Biden carried the state by outperforming Evers in the suburban counties around Milwaukee — known to political junkies as the “WOW” counties (Map 3). If Evers can’t match Biden in those suburbs, he will need to retain as much of his rural appeal as he can.

Map 3: Wisconsin, 2018 vs. 2020

Moving back to the Sun Belt, we don’t consider Gov. Brian Kemp (R-GA) to be an especially strong incumbent. In fact, for Kemp, what Trump giveth, Trump may also taketh away. During the 2018 primary, Kemp, then the Georgia secretary of state, was locked in a competitive race with then-Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle (R-GA). Though it wasn’t the only decisive factor, Kemp’s endorsement from Trump was certainly helpful. After finishing 13 percentage points behind Cagle in the May primary, Kemp won the runoff by a smashing 39% margin. In a contentious general election campaign against former state House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams, a Black woman who got national attention for her historic run, Kemp ran to the right. On Election Day, Kemp won with 50.2%, and avoided a runoff — under Georgia law, if no candidate receives a majority in the general election, a runoff is required.

Once in office, and despite governing as a conservative, Kemp made several moves that drew Trump’s ire. After a Senate vacancy arose in late 2019, Kemp appointed businesswoman Kelly Loeffler, snubbing Trump’s choice, then-Rep. Doug Collins (R, GA-9). After the presidential election, Kemp signed off on Georgia’s official vote count, which showed that Biden carried the state by 11,779 votes. To Trump, who insisted, without any proof, that the election was rife with voter fraud, this amounted to a betrayal — the former president promised to campaign against Kemp. As of last month, Collins was considering challenging Kemp, though other pro-Trump candidates may emerge. On the Democratic side, it’s easy to see Abrams clearing the primary field — since her loss, she’s stayed active in Democratic politics. As the two senatorial runoffs from earlier this year show, Democrats can win Georgia in non-presidential scenarios.

As an aside, one of the key differences between our current map and our initial map for the 2018 cycle was the positioning of Georgia and Florida. Four years ago, we started Florida, the more traditional battleground state, off as a Toss-up, while Georgia was in the Likely Republican category — this year, those are switched. In a state where Democrats have struggled to get their act together for much of the last decade, Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) has posted positive approval ratings and seems to be well-positioned.

The final race that the Crystal Ball sees as a Toss-up isn’t a swing state at the presidential level, but like Wisconsin, it features a Democrat who could be in for a tough race. In 2018, now-Gov. Laura Kelly (D-KS) had the benefit of running against a polarizing Republican, former Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach. While Kobach, who was known for his hardline stances on immigration, was outright toxic in the suburban pockets of the state — after Clinton narrowly carried the Kansas City-area KS-3, Kelly did so by almost 20% — Kelly was also able to keep the GOP margins down in the rural parts of the state: In KS-1, a sprawling, rural district that often gives Republicans over 70% of the vote, Kobach took just 51%.

Two big-name Republicans have gotten into the race already: former Gov. Jeff Colyer and state Attorney General Derek Schmidt. A Colyer nomination may give Democrats reason to bring up his old boss, former Gov. Sam Brownback (R-KS), who left office a deeply unpopular figure. Colyer, formerly the state’s lieutenant governor, took over the top job after Brownback left office for a diplomatic post in 2018 but then narrowly lost to Kobach in the gubernatorial primary. Had Colyer won the primary, he might have beaten Kelly in 2018. As Kelly won in 2018, Schmidt was elected to a third term as Attorney General 59%-41%, suggesting he may lack the baggage of some other Republicans.

Gov. John Bel Edwards’ (D-LA) reelection may offer somewhat of a template for Kelly. Edwards was first elected in 2015 — in a red state, he was running against a well-known but flawed Republican to replace another Republican who had low approvals. Edwards was reelected in 2019 over a less problematic opponent, but it was an all-hands-on-deck effort by state Democrats.

New England: Still defying political gravity?

On the gubernatorial map, no single region defies its presidential partisanship more than New England. Though Biden carried all six states in the region fairly comfortably, we don’t put any New England states in the Safe Democratic category.

In terms of personality and style, Maine may feature one of the biggest contrasts of any race. In 2018, then-state Attorney General Janet Mills won the open gubernatorial race to replace Republican Paul LePage. As governor, Mills has kept a low-key profile while LePage was known for his bombastic attitude. Since leaving office, LePage has worked as a bartender and even spent some time living in Florida. But back in Maine now, LePage seems intent on challenging Mills. We’d start LePage off as an underdog — if he follows through with his plans — but he did beat expectations last time he was on the ballot, in 2014. In fact, his strength in northern Maine’s 2nd District presaged Trump’s showing in the area two years later.

Moving one state west, we’re starting New Hampshire off as Leans Republican; until Gov. Chris Sununu’s (R-NH) plans are more solid, this will be something of a hedge rating. Sununu, who is broadly popular in the state, is under pressure from national Republicans to run for Senate against Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-NH) — Hassan also preceded him as governor. While Sununu isn’t term-limited, Granite State governors must face voters every two years. If he takes the plunge against Hassan, an open gubernatorial contest may look more like Toss-up. If Sununu runs for a fourth term as governor, we’d probably upgrade the GOP’s chances here.

In next-door Vermont, the only other state that requires its governors to run biennially, Gov. Phil Scott (R-VT) hasn’t announced his 2022 plans, but he is immensely popular. As one of the most moderate Republican officials in the country, he was reelected last year with nearly 70%, as Biden took about the same share up the ballot. Recently, Scott was tested in hypothetical polling against veteran Sen. Pat Leahy (D-VT) and was actually slightly ahead. Serving as governor and handling the day-to-day affairs of a state is one thing but going off to the Senate to vote with the national party is something else entirely. So we’re skeptical that, when push comes to shove, Scott, or any Republican, could win a federal race in Vermont. But for now, while Vermonters give national Democrats landslide margins, they seem content with electing moderate Republicans to state office. We’ll start this race off as Likely Republican, though an open seat situation would make for an attractive Democratic target.

Massachusetts, though its governors enjoy the luxury of four-year terms, is in much the same situation as Vermont. Gov. Charlie Baker (R-MA) was first elected in 2014 has and routinely ranked among the country’s most popular state executives. Last month, polling from MassINC showed him with a 74% approval rating; often, his numbers are higher with Democrats than Republicans. A frequent critic of Trump, Baker seems to also benefit from the electorate’s appetite for split government — as a Republican who emphasizes bipartisanship, he’s in a position to work with, and serve as a check on, the Democratic supermajorities in the legislature. With his fundraising picking up, it seems like he’ll run for a third term (there are no term limits in the Bay State). We’ll default to Likely Republican for now, but if he runs, Baker is a very strong bet for reelection.

Rhode Island has the nation’s newest governor, though it may also see competitive primaries. As then-Gov. Gina Raimondo (D-RI) was sworn in to lead the Department of Commerce earlier this month, her lieutenant governor, Dan McKee, replaced her in the Ocean State’s top office. McKee was first elected as lieutenant governor in 2014 and he survived a close primary from a more liberal challenger in 2018. As McKee looks to winning the governorship in his own right, another potential primary looms large. Both Secretary of State Nellie Gorbea and state Treasurer Seth Magaziner are term-limited in their positions, and either would be formidable opponents in a Democratic primary. Rhode Island is also expected to lose one of its two congressional districts, as a result of the 2020 census — rather than running against each other for the state’s sole seat, one of Reps. David Cicilline (D, RI-1) or Jim Langevin (D, RI-2) may run for governor.

Like other New England states, Rhode Island tends to be more receptive to local Republicans, and it has seen competitive state-level races over the last few decades. In fact, when Raimondo received 53% in 2014, it was the first time since 1992 that a Democrat claimed a majority of the vote in a gubernatorial race there (until 1994, it elected governors biennially). Still, given the strong Democratic bench, if McKee loses a primary, we think most of his potential foes would perform at least as well as he could in a general election. We’re starting Rhode Island off as Likely Democratic.

Rounding out New England, Connecticut may be in for a different type of gubernatorial election. After losing the keys to the governor’s mansion in 1990, Democrats were locked out until 2010. They’ve since strung together three victories, but the margins have been close. Despite the red environment of 2010, then-former Stamford Mayor Dan Malloy won an open seat race by six-tenths of a percentage point — on Election Night 2010, some networks called the race for him while he was still behind his GOP opponent. Even with subpar approval ratings throughout his first term, Malloy was reelected by about 3% in 2014, and now-Gov. Ned Lamont (D-CT) won by about that same amount in 2018.

With the pandemic, Lamont’s approvals numbers went up, and they haven’t come back down — last week, some polling found his approval rating at 71%. During Malloy’s time leading the state, his party’s standing in the legislature eroded: after 2016, for the final stretch of his tenure, the state Senate was tied and Democrats had only a slim majority in the state House. By contrast, in 2020, voters strengthened Lamont’s hand by giving him a supermajority in the state Senate while expanding the Democratic edge in the state House. Though he’s taking his time setting up his campaign, Lamont seems to be in a surprisingly strong position for reelection, so we see the race as Likely Democratic.

Democrats’ big three: Likely but not Safe

One of the things that most stands out about the Crystal Ball’s initial map is the lack of states that we consider to be Safe Democratic. Aside from Hawaii, which is actually open — though in gubernatorial races there recently, Democrats have generally won by wider-than expected margins — there aren’t any states that we’d place in that most secure category.

On one level, this reflects the nature of gubernatorial races — as mentioned earlier, in state-level contests, voters tend to be less partisan than in federal contests. Also, with the election roughly a year and a half away, a lot can change. But in three of the most populous states that they control, Democrats aren’t as well-off as they could optimally be.

After his initial landslide election in 2010, over a controversial Republican nominee, Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D-NY) fell into something of a holding pattern for 2014 and 2018. A moderate Democrat, he was never beloved by liberals. For his two reelection campaigns, he easily beat back underfunded challengers from the left in primaries, but would go on to win by double-digits in the general elections, as many of his Democratic critics held their noses for him. In the early months of the pandemic, Cuomo became a national figure — with many press outlets based in New York City, his daily briefings buoyed his profile and his approval ratings were stratospheric for much of the year. But more recently, Cuomo’s image has taken a massive hit. Criticism is mounting over his handling of the state’s nursing homes during the pandemic. Meanwhile, at least six women have come forward accusing the governor of sexual harassment. Last week, polling from Quinnipiac University found that, while New Yorkers don’t think the governor should resign, they would rather not see him stand for a fourth term (the state has no term limits).

Cuomo has not ruled out running again. On a historical, and lighter, note, his father, the late Mario Cuomo, was defeated in his bid for a fourth term in 1994 but immediately afterwards, landed a high-profile gig advertising Doritos chips. New York is a Democratic state, but to some degree, we’re waiting to see what Cuomo does. Despite facing calls to resign in early 2019, Gov. Ralph Northam (D-VA) rode out a scandal stemming from a mid-1980s photograph allegedly of Northam in blackface alongside someone dressed in KKK garb, plus another blackface incident from the same era where Northam was posing as Michael Jackson. Two years later, the Virginia governor has largely resuscitated his image, so perhaps Cuomo may be trying to follow a similar path. But in Virginia, which limits its governors to a single consecutive term, reelection is not an option for Northam anyway, and if a damaged Cuomo runs again, Republicans may be more competitive than usual.

In the heart of the Midwest, Illinois is a blue state, but it’s also one that doesn’t fall in love with its governors: it’s ousted two over the last two midterms. In 2009, as his legal troubles were compounding, an actor impersonating then-Gov. Rod Blagojevich (D-IL) on Saturday Night Live joked that in Illinois, having a governor end up in jail is “like flipping a coin and landing on tails.” While we consider Gov. J. B. Pritzker (D-IL) to be better off for reelection than some of his predecessors, there are a few uncertainties for Illinois Democrats on the horizon. In a referendum in 2020, voters defeated a tax proposal that Pritzker supported. Perhaps with that in mind going into an election year, the governor’s most recent budget excluded an income tax hike. Pritzker probably will be fine but we’re not going to start the race as Safe Democratic.

Finally, in California, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) made a strong debut in 2018 — aside from Hawaii’s term-limited David Ige (D-HI), he was the only Democratic candidate for governor to win with more than 60% of the vote that year. Ordinarily, Newsom would be a solid choice for reelection, but he faces the prospect of a recall election later this year, which injects some uncertainty into the picture.

In California, recalls are essentially a two-part proposition. On the ballot, voters are first asked whether the current governor should remain in office. A second ballot question lists a slate of replacement candidates — the incumbent governor is not eligible to be a choice. On the first question, if a majority of voters agree to replace the current governor, the candidate who gets the most votes on the second question becomes the new governor. In 2003, the last (and only) time such an effort has been successful in California, voters chose to recall Gov. Gray Davis (D-CA) by a 55%-45% margin, while Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger — with high name recognition from his acting career — got the most votes as the replacement candidate.

As of last month, Newsom’s approval rating was above 50%, but organizers of the recall claim that they’ll gather enough signatures to initiate the process. Republicans have also recruited one of their strongest candidates, former San Diego mayor Kevin Faulconer, and their 2018 nominee, businessman John Cox, is also running. Against either, Newsom likely would have little to worry about, but under recall rules, and out of an abundance of caution, we’re rating California as Likely Democratic.

Streaks to watch out for and some other notes

Though we don’t expect them to be among the most closely-contested races, two states we’ll be watching are Oregon and Arkansas — both carry some historical significance. Aside from its neighbor, Washington state, Oregon has the longest continuous streak of electing Democratic governors, as no Republican has won there since 1982. Oregon Republicans can sometimes come close — the last time the state saw an open seat contest, in 2010, Democrats held the governor’s mansion by just 1.5% — but putting together the final pieces of a winning coalition has proved challenging for them. Republicans had a credible candidate in 2018, former state Rep. Knute Buehler. But in what could be an ominous sign for the GOP, Buehler has since left the party. As Gov. Kate Brown (D-OR) cannot run for another term, we’ll start the race as Leans Democratic, though if Republicans have trouble finding a quality recruit, we may shift the race more in the incumbent party’s direction.

The Crystal Ball sees Arkansas as a safely Republican state, but some history could be made there next year. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, who served as former President Trump’s press secretary and is the daughter of former Gov. Mike Huckabee (R-AR), is running with Trump’s endorsement. Sanders will have a primary with state Attorney General Leslie Rutledge. In a general election, either would be heavily favored to replace outgoing Gov. Asa Hutchinson (R-AR) — in a sign of the times, this would mark the first time since Reconstruction that a Republican has handed off the Arkansas governorship to another Republican.

Looking to some more competitive states, aside from Evers and Kelly, we’re starting off all of the Democratic governors who were first elected in 2018 as favorites. In the west, it remains to be seen if Govs. Jared Polis (D-CO) or Michelle Lujan Grisham (D-NM) will draw credible opposition — both won open seats by solid margins in 2018 and are now in Likely Democratic races. Gov. Tim Walz (D-MN) was another solid performer that year, winning an open seat by a 54%-42% vote. This week, former Republican state Sen. Scott Jensen announced plans to run. Jensen represented Carver County, west of the Twin Cities, in the legislature, though another prominent local figure may make the race: Trump has reportedly encouraged MyPillow CEO Mike Lindell to run for governor. Given his outlandish statements after (and before) the election, Lindell would likely be a weaker nominee. In any event, we put Walz in the Likely Democratic category, as well.

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D-MI) saw her national stock rise with the COVID-19 pandemic last year. While Whitmer’s approval numbers are usually healthy, Republicans may be competitive, depending on their recruit. Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak (D-NV) also starts off a slight favorite, though some recent upheaval within the state Democratic Party may add a layer of uncertainty here. Biden carried Michigan and Nevada by about 2.5% apiece, so starting each off as Leans Democratic seems reasonable.

Two of Biden’s disappointments last year were Iowa and Ohio, on either side of the Midwest. Though polling showed him competitive in both, he lost them each by about 8%. In 2018, despite serious efforts, the story was similar for state Democrats. Govs. Kim Reynolds (R-IA) and Mike DeWine (R-OH) each won by about 3%. DeWine, who has upset some local Republicans with his COVID-19 restrictions, could potentially have more to worry about in a primary than a general election. No major Democrat has entered the race against Reynolds, though state Auditor Rob Sand hasn’t ruled out seeking a promotion. Both are Likely Republican for now.

Conclusion

Even though 2018 was, broadly, considered a “blue wave” year for Democrats, Republicans still won several of the most competitive gubernatorial races. So with local issues figuring more prominently into campaigns, statewide races are often more candidate-driven than federal elections, which are increasingly breaking along presidential fault lines. Going into the 2014 cycle, Republicans, who had a great year in 2010, were thought to be overexposed. But by running candidates who fit their states, like Hogan in Maryland and Baker in Massachusetts, the GOP ended the cycle with a net gain of statehouses.

Hopefully by 2022, the COVID-19 pandemic will have subsided. While many governors are still riding high from their handling of the pandemic, more “conventional” issues may be dominating gubernatorial campaigns by then — perhaps this will lead to more competitive races.

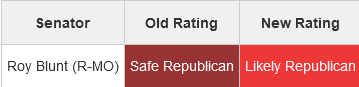

P.S. Missouri Senate to Likely Republican

Table 1: Crystal Ball Senate rating change

On Monday, Sen. Roy Blunt (R-MO) became the fifth Republican senator of the 2022 cycle to announce his retirement. Blunt’s departure may open the door to a competitive GOP primary in the Show Me State. Democrats may look harder at the contest as a long shot opportunity, especially if former Gov. Eric Greitens (R-MO), who left office in disgrace in 2018 but is reportedly eyeing a comeback, is nominated.

To be clear, we recognize that Missouri, which gave Trump 57% of the vote last year, is not the bellwether that it once was. If he were around today, Harry Truman, the state’s favorite son, might not even be able to win there as a Democrat. But for now, we’re keeping the race at the right edge of the playing field.

J. Miles Coleman is an elections analyst for Decision Desk HQ and a political cartographer. Follow him on Twitter @jmilescoleman.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.