The Minnesota Twins: A Complete History of Double-Barrel Senate Elections

A Commentary By Geoffrey Skelley

Sen. Al Franken’s (D) impending resignation due to sexual harassment allegations will create a vacancy in Minnesota’s Class II Senate seat, precipitating a special election in the North Star State next November. Gov. Mark Dayton (D) announced last week that he would name Lt. Gov. Tina Smith (D) to the post, and Smith said that she intends to run in the 2018 special election for the remainder of Franken’s term (the seat is due to be regularly contested in 2020). Because Franken did not immediately resign, there was some speculation that he might reconsider leaving office — among others, Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) wants Franken to remain in the Senate — but his spokesman said on Wednesday that Franken intends to resign on Jan. 2, 2018, and that Smith will be sworn into office on Jan. 3. This article is based on the assumption that Franken will indeed resign.

The special election for Franken’s seat is notable not only because it puts a potentially competitive seat on the 2018 map but also because it will coincide with the regular election for Minnesota’s Class I seat, held by Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D), who is seeking reelection. With the appointment of Smith, Minnesota will become the sixth state to ever be represented by an all-women Senate delegation and the fourth currently (California, New Hampshire, and Washington presently have two women senators). With another of what we call “double-barrel” elections, Minnesota’s pair of Senate races will mark the 55th time a state has had contests for both of its seats on the same day in the popular election era (which covers roughly the last century).

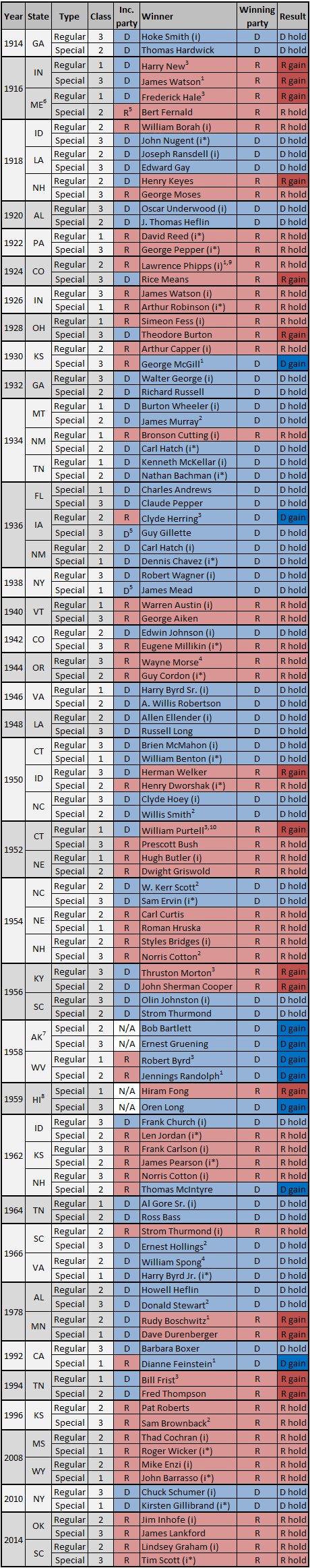

We previously reviewed double-barrel Senate elections early on in the 2014 election cycle, but in that case we didn’t include three irregular election pairs in Alaska, Hawaii, and Maine that took place at times different from the standard federal Election Day in November. Additionally, we missed a Colorado duo from 1924, and the original article, which was pegged to a double-barrel Senate election in South Carolina in 2014, predated the events that led to Oklahoma also having a double-barrel election that year. Table 1 below shows all 54 pairings since 1913, when popular elections for the U.S. Senate were established by the ratification of the 17th Amendment.

Table 1: Double-barrel U.S. Senate elections, 1913 to present

Notes: “(i)” denotes an elected incumbent and “(i*)” denotes an appointed incumbent. “N/A” denotes that no party held a seat previously in Alaska and Hawaii because these were the first elections for the U.S. Senate in those states. Concurrent regular and special elections for the same Senate seat are not included as double-barrel elections. Click here to download this table.

Footnotes: (1.) Winner defeated an appointed incumbent from the other party in the general election. (2.) Winner defeated an appointed incumbent for the party nomination and won the general election. (3.) Winner defeated an elected incumbent from the other party in the general election. (4.) Winner defeated an elected incumbent for the party nomination and won the general election. (5.) Seat was vacant at time of election and is labeled with last party to control. (6.) Non-presidential elections in Maine took place in September prior to 1960. (7.) Alaska elected its first U.S. senators concurrently on Nov. 25, 1958, prior to the granting of its statehood on Jan. 3, 1959. (8.) Hawaii elected its first U.S. senators concurrently on July 28, 1959, prior to the granting of its statehood on Aug. 21, 1959. (9.) Sen. Lawrence Phipps (R-CO) won reelection by defeating fellow Sen. Alva Adams (D-CO), who had been appointed to fill a vacancy in Colorado’s Class III seat but ran against Phipps in the Class II seat instead of running in the special election for the Class III seat. (10.) William Purtell (R-CT) won the nomination for Connecticut’s Class I seat to face Sen. William Benton (D-CT) in May 1952, was subsequently appointed to fill the state’s Class III seat after Sen. Brien McMahon (D-CT) died in July, and then went on to defeat Benton for the Class I seat in November.

The main takeaway from Table 1 is the fact that the same party tends to win both seats in a double-barrel Senate election. In 54 cases, just eight have featured split-ticket outcomes. More importantly for Minnesota in 2018, the last time a split-ticket outcome occurred was in 1966. That year, Sen. Strom Thurmond (R-SC) won reelection for South Carolina’s Class II seat while former Gov. Ernest “Fritz” Hollings (D) defeated the Democratic appointee in the special primary for the Class III seat and then won the general election. But Thurmond had switched parties in 1964, leaving the Democratic Party because of civil rights legislation. In the 10 double-barrel contests after 1966, the same party has won both seats every time. While some of the states that have held such elections in those 10 cases were relatively safe for one party or the other, three elected or appointed incumbents did lose in them: appointed Sen. Wendell “Wendy” Anderson (D-MN) lost to businessman Rudy Boschwitz (R) in 1978 (more on that below), appointed Sen. John Seymour (R-CA) lost to former San Francisco Mayor Dianne Feinstein in 1992, and elected Sen. Jim Sasser (D-TN) lost to future Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R) in 1994.

Given the straight-ticket pattern in such elections, Minnesota’s historical Democratic lean, and the likelihood of a pro-Democratic environment next year (to an unknown extent at this point), it seems at this early juncture that a Democratic sweep in Minnesota in 2018 may be more likely than not. But time will tell — Minnesota has consistently trended toward the GOP in presidential elections even while remaining the second-most Democratic state in the Midwest (behind only Illinois), so we’re certainly not writing off a GOP win in Franken’s soon-to-be-old seat.

We will talk more generally about double-barrel elections, but first let’s dig into Minnesota’s history with such elections. The 2018 election will mark the second time Minnesota has had concurrent contests for both of its Senate seats. Republicans won both seats in 1978 as part of what was known as the “Minnesota Massacre,” where Democrats lost control of both Senate seats as well as the state’s governorship.

The setup for Minnesota’s 1978 election cycle involved a number of fascinating moving parts. In 1976, Sen. Walter Mondale (D-MN) won the vice presidency as Jimmy Carter’s running mate on the Democratic ticket, creating a Senate vacancy. Gov. Wendell Anderson (D), in the middle of his second term as Minnesota’s governor, opted to resign the governorship and have his successor, Lt. Gov.-turned-Gov. Rudy Perpich (D), appoint him to replace Mondale in the state’s Class II Senate seat. In the lead-up to the 1976 election, as debate grew over what should happen to Mondale’s seat if the Carter-Mondale ticket won, it was fairly clear that Minnesotans took a dim view of Anderson’s eventual arrangement. A late September survey on behalf of the Minneapolis Tribune newspaper (today the Star Tribune) asked respondents if Anderson should resign and be appointed to Mondale’s seat, or if Anderson should appoint someone else. In the poll, 55% said Anderson should appoint someone else while only 23% supported Anderson maneuvering to become a senator. This included 49% opposition among Democratic-Farmer-Labor (the name of the Democratic Party in Minnesota) identifiers compared to 28% support. But despite the potential blowback, Anderson followed through. He would face the voters in a regularly-scheduled election in 1978 — the Class II seat was due to be contested then, regardless of the vacancy. There was sufficient irritation among Minnesotans, including Democrats, over Anderson’s appointment that the Minnesota House of Representatives — controlled three-to-one by the DFL — responded to public pressure by passing a bill in 1977 that would have provided for a special election within 12 to 14 weeks of a U.S. Senate vacancy. But the bill died in the DFL-controlled Minnesota Senate.

Meanwhile, the health of Minnesota’s other senator, the legendary Hubert Humphrey (D), was deteriorating due to bladder cancer. After his defeat in the 1968 presidential election, Humphrey returned to the Senate by winning an open-seat election in 1970 for Minnesota’s Class I seat and easily won reelection in 1976 (Humphrey had first been elected to Minnesota’s Class II seat in 1948 and served there until taking office as Lyndon Johnson’s vice president following the 1964 presidential election; Mondale was appointed to take Humphrey’s place). Humphrey died on Jan. 13, 1978, creating a vacancy that would necessitate a special election in 1978, which would coincide with the regular election for the state’s other seat, held by the appointed Anderson. On Jan. 25, Perpich appointed Humphrey’s wife, Muriel, to fill the seat by Perpich, though not expressly as a “caretaker” appointment — she said the election was too far off for her to know if she’d run in the special election. While Muriel Humphrey announced she wouldn’t run in early April, the weeks of discussion regarding the prospect of yet another unelected Democrat running for reelection may have exacerbated the already-negative environment for Democrats in 1978.

As it was, Minnesota Republicans (at that time, technically the Independent-Republicans, or I-Rs) were well-positioned to fight for both Senate seats in part because a Democrat occupied the White House in 1978 — midterm elections often break against the White House party. But the kerfuffle over appointments and unelected DFL incumbents also helped the GOP. Al Quie (R), the eventual Republican nominee for governor, tapped into the dissatisfaction by putting up billboards across the state that read: “Something scary is going to happen to the DFL. It’s called an election.” Highlighting the fact that the state’s two U.S. senators, governor, and lieutenant governor were all unelected Democrats, the sign became a famous part of the 1978 campaign.

The final nail in the Democrats’ coffin was the division between the party’s liberal and more conservative factions — a schism partly due to abortion views — that was exposed in the DFL nomination contests for both Senate races. The DFL convention served as a warning shot for disunity. Needing 60% of the delegates to earn the party’s endorsement, the moderate Anderson only narrowly surpassed that mark on the first ballot for his Class II seat, while it took three ballots for liberal Rep. Donald Fraser (D) to clinch the party endorsement for the Class I seat. But the convention endorsements didn’t allow the party to avoid contested primaries, especially in the case of the Class I seat. In that race, conservative businessman Bob Short (D) — who bypassed the convention — defeated Fraser in the Sept. 12 primary 48.0%-47.4% to win the Democratic nomination. Because of Short’s nomination, some liberals defected to Dave Durenberger (R) in the general election. As for Anderson, he fended off his more liberal convention opponent in the primary, but still only won 57%, a mediocre mark for an incumbent senator and twice-elected former governor.

In the general election, the divided Democrats suffered huge losses. Durenberger defeated Short 61%-35% in the Class I special election while Rudy Boschwitz (R) beat Anderson 57%-40% in the Class II contest. Perpich, who had appointed Anderson and Muriel Humphrey to the Senate, lost 52%-45% (though he would win the governorship back in 1982 and win reelection in 1986). The weak top-of-the-ticket performance for Democrats helped Republicans double their seat total in the state House of Representatives and also elect Arne Carlson (R) state auditor (Carlson would defeat Perpich in 1990 when the Democrat sought his third consecutive term in a truly wild election).

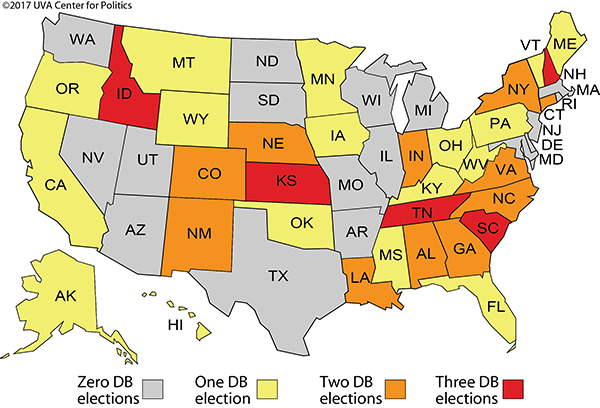

With both seats up in 2018, this will be Minnesota’s second double-barrel Senate election, which will make it the 17th state to have had at least two different years with concurrent contests for both Senate seats. The state count is laid out in Map 1 below.

Map 1: Number of double-barrel Senate elections by state as of 2017

Five states have had three pairs of concurrent Senate elections for both senate seats while 11 others have had two. Including Minnesota for the time being, 17 states have had one and 17 other states have had none.

Three of the states with only one such election are Maine (1916), Alaska (1958), and Hawaii (1959), and they are worth discussing because none of their double-barrel contests took place on the standard, early November federal election date. In the case of Maine, that’s because prior to 1960 Maine held all non-presidential elections in September. The phrase “as Maine goes, so goes the nation” came from the Pine Tree State’s early elections, which tended to provide a clue as to how the rest of the country would vote in November. In 1916, the state had concurrent Senate elections on Sept. 11: Frederick Hale (R) defeated incumbent Sen. Charles Johnson (D) in the regularly-scheduled contest for Maine’s Class I seat, and ex-Gov. Bert Fernald (R) won the special election for the Class II seat. Notably, the GOP candidates didn’t win by very large margins in the Republican-leaning state (seven and nine percentage points, respectively), perhaps foreshadowing the November presidential result, where President Woodrow Wilson very narrowly won reelection against Republican Charles Evan Hughes. But Maine lost its supposed bellwether status after the 1936 election cycle: GOP victories in September seemed to augur poorly for President Franklin Roosevelt, who then won every state except Maine and Vermont in the presidential contest. This led to the famous alteration of the phrase about Maine by FDR’s campaign manager, James Farley: “As Maine goes, so goes Vermont.”

As for Alaska and Hawaii, their elections took place just prior to statehood. Alaska held elections for statewide office on Nov. 25, 1958 — three weeks after the Democratic wave in the 1958 midterm — and elected long-time territorial Delegate E.L. “Bob” Bartlett (D) to one Senate seat and former territorial Gov. Ernest Gruening (D) to the other, providing two more net seats for Democrats in 1958, bringing their gains to 15 Senate seats. Eight months later, it was Hawaii’s turn to elect statewide officers as it got ready for statehood. On July 28, 1959, the Aloha State split its Senate ticket, electing former territorial Gov. Oren Long (D) and former territorial legislator Hiram Fong (R).

There are interesting stories associated with every double-barrel election in Table 1, and we recommend taking a look at our article from late 2012 on the subject, which contains other engaging details.

To close, we will mention — with great trepidation — something to consider when thinking about double-barrel Senate elections in 2018. Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) was admitted to Walter Reed Medical Center to receive treatment related to his ongoing battle with glioblastoma, a lethal brain cancer. We fervently hope that the senator can overcome this very serious health challenge. Still, a vacancy in that seat, because of resignation by McCain due to his health troubles or worse, is a possibility. Arizona’s other Senate seat, held by retiring Sen. Jeff Flake (R), is up in 2018 and is already one of the most watched races in the country. Regrettably, it is not out of the question that the Grand Canyon State could have its first-ever double-barrel Senate election in 2018, with potentially major consequences for the balance of power in the upper chamber. We sincerely hope that Arizona will have only one Senate race next year.

One other possibility, given the sexual harassment accusations that seem to emerge daily against powerful men across American life, is that someone else in the Senate will, like Franken, be forced to resign, perhaps necessitating another double-barrel Senate election somewhere else next year. We say this with no inside knowledge, but rather just as a caveat that is worth keeping in mind in a tumultuous time.

Geoffrey Skelley is the Associate Editor at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

See Other Political Commentary by Geoffrey Skelley

See Other Political Commentary

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.