2010 Primaries: Gauging Anti-Incumbent Sentiment

A Commentary by Rhodes Cook

The 2010 primary season is under way, which at the congressional and gubernatorial levels is often no more than a quiet backwater in America’s electoral process. In recent years, only a few such incumbents have lost their bids for renomination, and only a handful more have had to break a sweat.

No sitting senator or governor has lost a primary bid since 2006—when Democratic Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut and Republican Gov. Frank Murkowski of Alaska were both defeated. Meanwhile, just two House members were denied renomination in 2006. In 2008, there were only four.

But this year could be dramatically different. Distaste with government is palpable. In last month’s first-in-the-nation primary in Illinois, Democratic Gov. Pat Quinn came within 10,000 votes of losing his party’s gubernatorial primary. This week in Texas, Republican Gov. Rick Perry won renomination by making the Washington experience of his principal rival, Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, more odious to GOP primary voters than his own long run in Austin.

To be sure, no House incumbents were defeated in either Illinois or Texas, or for that matter, were even closely contested. But by modern standards, it would still be quite noteworthy if even six or seven House members, and a senator and governor or two, were beaten over the course of the primary season.

Several basic questions flow from all this: How high, really, will the level of anti-incumbent sentiment be in 2010? Will it be aimed almost exclusively at the Washington-ruling Democrats or will it envelop a significant number of Republican officeholders as well? Or might it play out on a piecemeal basis—in favor of a populist outsider such as Sen. Scott Brown, and against an experienced Washington hand such as Sen. Hutchison?

Primary voters over the course of the next few months will help provide answers, which should better define the true nature of the political landscape heading toward November.

In historical terms, the number of memorable primary seasons has been limited.

First to mind is 1938, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried unsuccessfully to purge powerful conservative congressional Democrats from the New Deal coalition.

Then there is 1946, a major transitional year in American politics immediately after World War II. Eighteen House incumbents were beaten in primaries, while a slew of others led by John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon made their first steps onto the political ladder by winning their party’s congressional nomination and ultimately a seat in the House of Representatives.

And finally there is 1992, when the combination of redistricting and the House banking scandal lashed at the Democrats and served as a precursor of the anti-incumbent tide that would rout them from Congress two years later. Altogether, 19 House members were beaten in the primary season of 1992, a post-World War II record. Fourteen of them were Democrats.

In recent decades, only the years that end with “2” routinely see much primary action on the House side. That is when the lines have been redrawn following the decennial census and incumbents are forced to take in new terrain that that they have not been representing. Some even find themselves paired against each other in the same district.

After that, House members tend to settle in for the rest of the decade, at least in terms of the primaries. And by the time the election year rolls around that ends with “0,” the political scene is usually quite placid. In 2000, just three congressional incumbents lost renomination bids. In 1990, it was just one.

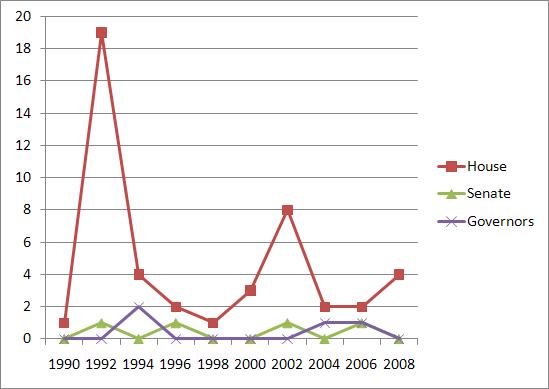

Chart 1. Primary Elections: Usually a Low Hurdle for House, Senate and Gubernatorial Incumbents

For congressional and gubernatorial incumbents, party primaries are usually a low hurdle on the path to reelection. Primary losses by sitting senators or governors are few and far between. Only four of each have lost primary bids for renomination since 1990. Meanwhile, significant primary losses for House members have tended to be concentrated in election years that end with “2.” They are the ones that follow the decennial congressional reapportionment and redistricting, with a degree of political upheaval caused by the drawing of new district lines.

Note: An asterisk (*) indicates that in spite of Sen. Joe Lieberman’s loss in the 2006 Democratic primary, Connecticut law enabled him to run for reelection that November as an independent, a race that he won.

Sources: Vital Statistics on Congress 2008 (Brookings Institution Press) for House and Senate incumbents defeated in primaries from 1990 through 2006; America Votes (CQ Press) for House incumbents defeated in 2008 and gubernatorial incumbents since 1990.

Unlike a general election, primary seasons are hardly ever affected by large national waves that send a host of incumbents to the political sidelines. Rather, officeholders are usually rejected by their party’s voters for a variety of individual reasons, beginning with personal ethics scandals and controversial voting records.

Lieberman, for instance, got in trouble with many Connecticut Democrats for his support of the Iraq war. Murkowski alienated many Alaska Republicans with displays of high-handedness, including the appointment of his daughter to his vacant Senate seat. He ultimately lost the Republican gubernatorial primary in 2006 to Sarah Palin; Lieberman ran for reelection that year as an independent and won.

But this year could be the rare election year with overarching themes that could spell primary problems for a number of incumbents in both parties.

On the Republican side, an “insider-outsider” dynamic is developing in many states. Conservative activists—many part of the “tea party” movement—are promoting primary candidates against those favored by the GOP establishment.

In Arizona, Sen. John McCain, the party’s 2008 presidential nominee, is facing a primary challenge from former Rep. J.D. Hayworth. In Utah, three-term senator Robert Bennett has drawn an array of intra-party challengers. In Florida, Republican Gov. Charlie Crist has encountered serious resistance in his bid for the GOP Senate nomination from former state House Speaker Marco Rubio, who has emerged as a darling of conservative activists nationwide.

And in Kentucky, Secretary of State Trey Grayson, who has the backing of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, is being challenged for the party’s Senate nomination this year by Rand Paul, the son of Republican Rep. Ron Paul. The latter’s libertarian campaign for the 2008 GOP presidential nomination made him a hero to many conservative activists of his ilk, and that loyalty is being transferred in some measure to his son.

On the Democratic side, most of the high profile primaries on tap thus far feature incumbents that have the White House imprimatur running against active and potential challengers who do not. President Barack Obama has already lined up behind Sens. Michael Bennet in Colorado, Arlen Specter in Pennsylvania, and Kirsten Gillibrand in New York. And at the House level, Obama provided a primary-eve endorsement to Sheila Jackson Lee, who used it to help turn back a pair of challengers in her Texas congressional district on Tuesday.

As for Bennet and Specter, they have significant primary opposition (former state House Speaker Andrew Romanoff and Rep. Joe Sestak, respectively). Gillibrand thus far has escaped serious intra-party competition, with former Rep. Harold Ford of Tennessee the latest Democrat to explore a primary challenge to Gillibrand before pulling back.

Sen. Blanche Lincoln of Arkansas is not so fortunate. Already embattled, she has recently drawn a primary opponent in the form of Democratic Lieut. Gov. Bill Halter. But it is unclear what role, if any, the White House will play in a state where Obama is not inherently that popular.

In terms of both the Democrats and Republicans, this could be just the tip of the iceberg as to the turmoil that could embroil the 2010 primary season. Only two states have held their nominating contests thus far. The remaining 48 will vote from early May to mid-September, with the primary filing deadline still well in the future in many of them.

And if the primaries do turn volatile, it would validate a bit of conventional wisdom that so far has yet to be proven—namely, that both parties have moved so far from the center in recent years that satisfying the party base in a primary can be tougher for a candidate than winning a general election. The actual results in recent years have yet to prove that. But a turbulent primary season in 2010—with a slew of incumbent defeats—just might.

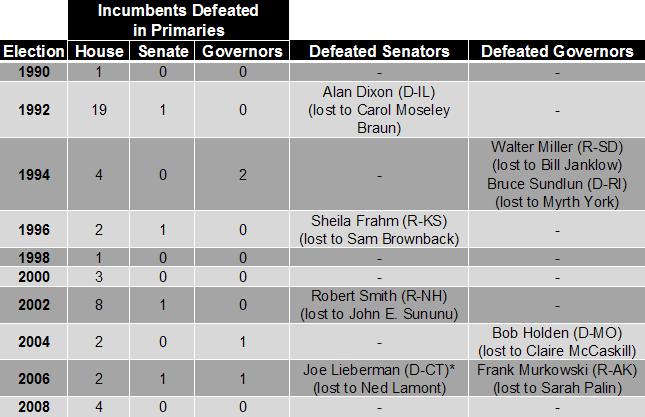

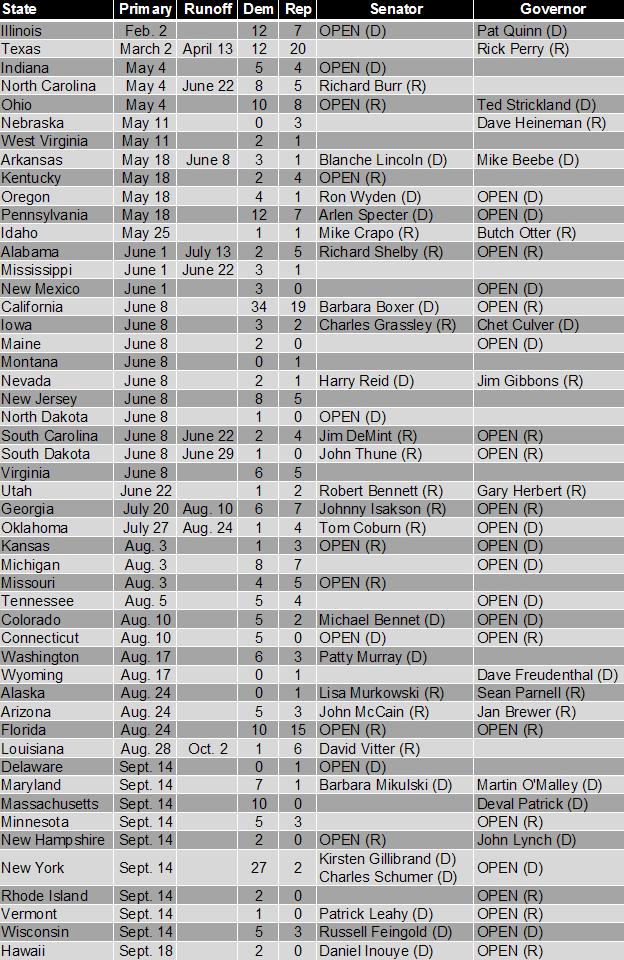

Chart 2. 2010 Primary Calendar

The 2010 primary season starts slowly with one state voting in February (Illinois) and another in March (Texas). But once it gets rolling in May, there is virtually non-stop primary action across the spring and summer months until the nominating season ends in mid-September. The two big days of primary voting are June 8, when 10 states from Maine to California will be nominating candidates, and Sept. 14, when nine states anchored by New York will be holding primaries.

Note: The partisan breakdown of House seats reflects the result of a special election and a party switch since 2008. Current vacancies, however, are credited to the party that last held the seat.

Source: Federal Election Commission.

Rhodes Cook is a senior columnist at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia

See Other Commentary by Rhodes Cook

See Other Political Commentary

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.