Nebraska Senate: Osborn launches second run

A Commentary By J. Miles Coleman

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— In Nebraska, Dan Osborn, an independent candidate who held Sen. Deb Fischer (R) to a single-digit win last year, announced he’d challenge Sen. Pete Ricketts (R).

— Though Ricketts should be more formidable than Fischer, Osborn is still a credible challenger, so we are moving the race from Safe Republican to Likely Republican.

— We are also rating an imminent special election in TN-7 as Likely Republican. Republicans are still clearly favored to hold it but the dynamics of recent low-turnout special elections could make it more competitive than one might otherwise think.

— There will be a trio of special elections in some deep blue districts later this year. While Democrats are heavy favorites to retain them all, AZ-7 could represent an opportunity to see if the GOP’s recent gains with Latinos are sticking.

Nebraska Senate: Osborn launches second run

Virtually all Senate cycles in recent memory have included one, or both, of either 1) a popular former or outgoing governor running in a state that usually goes against their party in presidential races or 2) a well-funded independent candidate acting as a stand-in for a Democrat against a GOP incumbent.

The 2026 cycle, at least so far, lacks a contender from the former category. In fact, if anything, going the opposite route is becoming popular: senators are increasingly liking the idea of becoming governors.

Earlier this year, former Gov. Chris Sununu (R-NH) again passed on a Senate run. Ever since he became ineligible for a third term, now-former Gov. Roy Cooper (D-NC) rose to the top of national Democrats’ recruitment wish list in the Tar Heel State—and the pressure on Cooper only seemed to increase when Sen. Thom Tillis’s (R) seat opened up. Though North Carolina is basically a light red state in federal elections, the combination of a potentially blue environment and Cooper’s strong favorability ratings could be enough to put Democrats over the top. It seems possible that Cooper may announce his plans within the next few weeks. In any case, other governors from marginal states who have passed on open-seat Senate races this year include Georgia’s Brian Kemp (R) and Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer (D), both of whom seem to be more interested in 2028.

Getting into the second category, none of the red state independent candidates that Democrats have strategically backed over the last decade or so have actually beaten Republican incumbents. Last year’s Nebraska Senate contest resulted in the closest such call, though: Sen. Deb Fischer (R) won a third term by less than 7 points against former union leader Dan Osborn as Donald Trump carried the state by just over 20 points. That result, due to both the composition of the overall Senate map and Osborn’s lack of a party label, made Fischer the Republican incumbent who came closest to losing reelection that cycle.

After his loss, Osborn seemed to be keeping his options open for a future run. As part of his overall showing, he carried the state’s 1st District, a seat that includes Lincoln and has rarely gone against Republicans in recent decades. For Democrats looking to regain control of the House, Osborn would have probably been their strongest recruit in what would be a reach seat (assuming he’d caucus with them if elected).

But, for a time, Osborn reportedly was instead considering challenging Rep. Don Bacon (R) in the Omaha-centric 2nd District—Bacon has since announced his retirement. Though it is hard to speculate about internal party politics, the feeling among Omaha-area Democrats could have been that, in a district that has voted blue at the presidential level for the last two cycles, they might not need to step aside for an independent candidate. While Osborn carried it by 12 points, NE-2 was also the district where he generated the least crossover appeal: it was the only one of the three districts where he ran just single-digits ahead of Kamala Harris. Omaha’s broader leftward trend has had something to do with its white collar voters—a group that Osborn’s pitch as a candidate of and for the working class did not seem tailored to.

But, earlier this week, after months of floating the prospect, Osborn formally announced that he’d run for Senate again. Sen. Pete Ricketts (R), who was appointed in 2023 and won a special election that was concurrent with last year’s general election, will seek a full term in 2026. With this, the Nebraska race moves from Safe Republican to Likely Republican.

We ended last year’s regular Senate race in Nebraska as Leans Republican, which matched up nicely with Fischer’s 53%-47% win. So why are we rating the 2026 race as a level better for Republicans?

Though some appointed senators have struggled to defend their seats in recent cycles, this was not the case for Ricketts: his 25-point margin last year was stronger than Trump’s showing in the state. While Ricketts lacked well-funded opposition, he took almost 90,000 more raw votes than Fischer.

Osborn enters the 2026 cycle with higher name recognition than he had two years ago, although we wonder if that comes at the cost of losing the element of surprise—something that seemed like a crucial ingredient in propelling him into contention against Fischer. Last summer, as Democratic donors looked frantically for a legitimate offensive opportunity outside of Florida and Texas, Osborn’s campaign habitually put out internal polls showing a close race in Nebraska. When he began to raise serious cash, outside Republicans got involved, if perhaps somewhat begrudgingly, on behalf of Fischer. This time, national Republicans clearly wanted to cover their bases in Nebraska: in May, One Nation, a conservative outside group, began running ads boosting Ricketts. Once the campaign begins in earnest, Ricketts will have the additional benefit of being able to self-fund, as he is from a wealthy family.

Last year, it probably worked to Osborn’s advantage that Fischer was less defined than Ricketts. During her time in the Senate, Fischer kept a low profile. That anonymity probably made it easier for the Osborn campaign to define her (one of his ads compared her to Hillary Clinton). Meanwhile, Ricketts entered the Senate shortly after serving two terms as a popular governor. In his announcement video, Osborn fashioned himself as the more populist candidate by bringing up Ricketts’ generational wealth, but we wonder if those attacks will have the same impact.

Even if we view Ricketts as a tougher opponent than Fischer, one factor in Osborn’s favor this time could be a bluer national environment. In his first campaign, Osborn also distanced himself from the Democratic Party, at least rhetorically, to an extent that other recent independents did not seem willing to—he talked about helping Trump build his much-mentioned border wall, for instance. This is something Osborn will almost certainly have to lean further into now. Though Osborn feuded publicly with the state Democratic Party last year, they ultimately did not run their own nominee against him—according to the Downballot, state Democrats will similarly not recruit candidates to run in the 2026 race.

The sole public poll of the race was put out by Osborn back in April, and showed Ricketts with a 46%-45% lead (and of course, internal polls released by a candidate are often designed to send some type of message).

Overall, Democrats are still looking for obvious offensive opportunities beyond Maine and North Carolina. While Ricketts is still a clear favorite for a full term, Nebraska is now a live contest in a way that it wasn’t before this week.

Checking in on special elections

A little over a month ago, Rep. Mark Green (R, TN-7) announced that he’d resign his seat to take a private sector job. Though his resignation would mean a temporary vacancy on the GOP side, Green was at least a bit of a team player on his way out, as he said he would not leave Congress until Trump’s so-called One Big Beautiful Bill passed. On Friday, Green followed through, designating July 20 as his last day in the House.

The timing of the special election seems somewhat up in the air: while the special general election could be held on November 4—in conjunction with this year’s gubernatorial races in New Jersey and Virginia—it could also be later that month, or even in December. There is some uncertainty about the state’s election law and how it may conflict with federal law, per the Nashville Banner. Primaries would presumably take place in late summer or early autumn.

The district that Green was originally elected to in 2018 would have gone on to back Trump 70%-29% in 2024. During redistricting, though, Republicans cracked the Democratic-held TN-5, which was then basically coterminous with Nashville’s Davidson County. While TN-5 was turned into a red seat, TN-7 necessarily took in more Democrats: the current version contains a quarter of Davidson County and backed Trump by a lesser, but still comfortable, 60%-38%.

Even if the current TN-7 is not as conservative as its past iteration, the district has reddened over the past decade or so. In 2012, for instance, its presidential result was considerably closer than what it saw last year, as it backed Mitt Romney by only a 55%-45% vote.

The details of that shift are complex and somewhat surprising.

The eastern part of the district consists of a handful of rural counties that have abandoned their Democratic heritage: Barack Obama lost that area 63%-37%, but by 2024, Harris got blown out 80%-20% there. While that was a strong shift, it was not exactly surprising to see Trump-era Democratic margins crater in the rural South. Moving west, Montgomery County (Clarksville) and three counties that orbit Davidson County account for a majority of the district’s population. Despite healthy population growth, this group, on the whole, has remained relatively stagnant, backing Republican nominees by about 30 points in both 2012 and 2024.

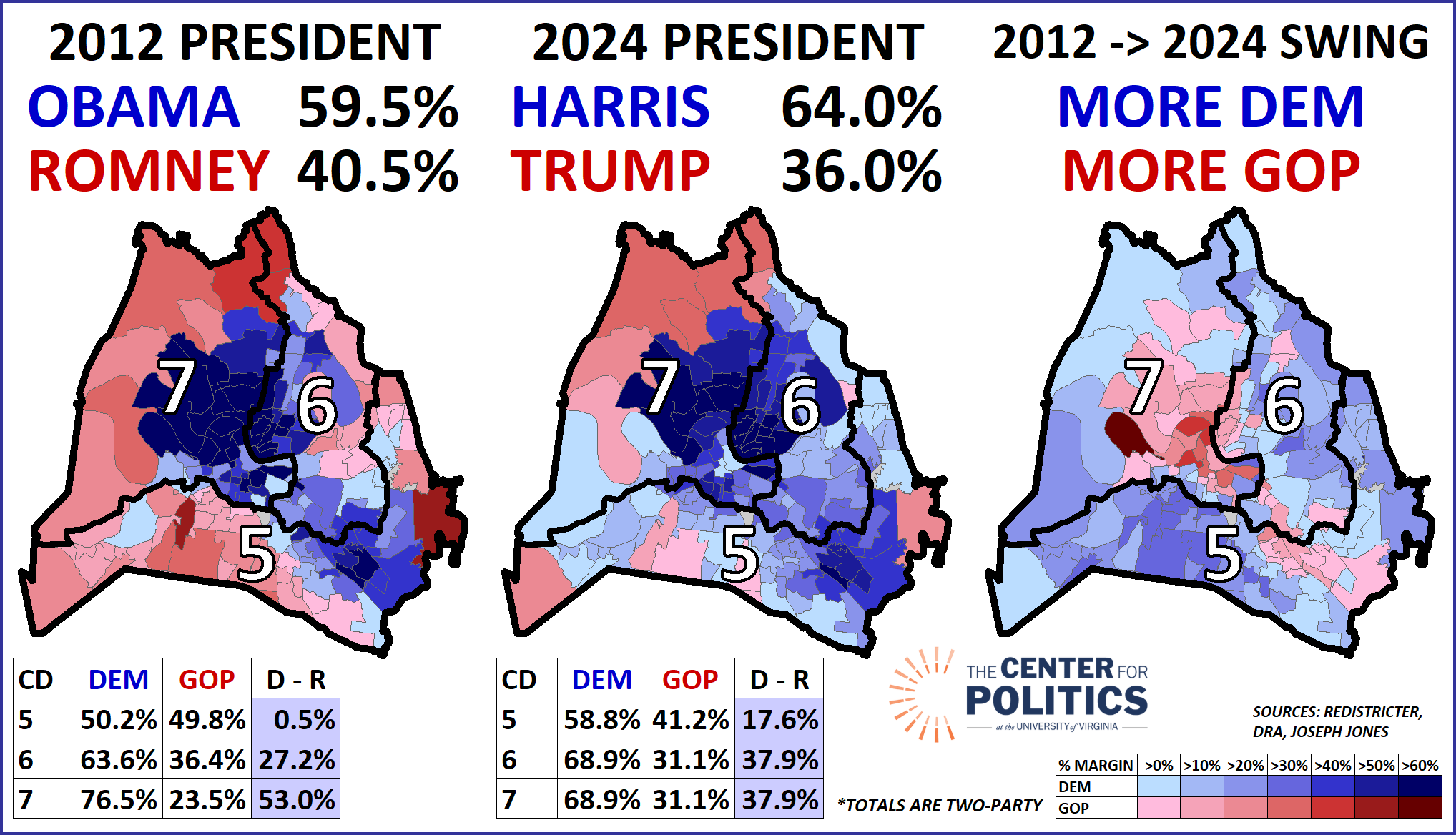

Things get more interesting around Nashville. While the Davidson County portion of this seat, which includes much of Downtown Nashville, is still very blue, it has also seen some clear movement to the right. While Davidson County as a whole became 9 percentage points bluer since 2012, Harris’s 38-point two-party margin in the TN-7 part of the county was down from Obama’s 53-point two-party margin. Map 1 shows Davidson County, broken down by district, between those elections:

Map 1: 2012 vs 2024 in Davidson County, TN

As the last image implies, Republican mappers put the reddest-trending parts of the county in District 7. These changes have probably been informed by demographics. According to Redistricter’s data, in 2010, the TN-7 slice of Davidson County was evenly divided in terms of its racial demographics, at 47% white and 46% Black. But by the 2020 census, that split grew to 51%-35%, as it added about 22,000 white residents while losing 5,400 Black residents. So, the voters who are gentrifying Nashville’s closer-in neighborhoods are not the white liberals that have flocked to other southern metros, like New Orleans and Atlanta, and who give Democrats near-unanimous margins. Despite this longer-term trend, in a special election we’d still expect this part of the district to punch at least a little above its weight for Democrats both in terms of turnout and performance.

Not surprisingly, the Republicans have a deep bench in the district. As of earlier this week, a handful of Republican candidates had entered the race. Names included state Reps. Lee Reeves, Jody Barrett, and Jay Reedy, Montgomery County Commissioner Jason Knight, former state General Services Commissioner Matt Van Epps, and Army veteran Jonathan Thorp. Tennessee lacks runoffs, so it is not uncommon for primary winners to secure their nominations with small pluralities: TN-6’s 2010 Republican primary and, more recently, TN-1’s 2020 Republican primary are examples. Democrats have a competitive primary of their own, as state Reps. Bo Mitchell and Aftyn Behn have both announced their campaigns for the seat.

We are starting the 2025 special election as Likely Republican, despite the heavy GOP lean of the seat. Earlier this year, Democrats logged double-digit overperformances in a pair of Florida districts that are even redder. The trajectory of those races seemed to play some role in prompting President Trump to withdraw Rep. Elise Stefanik’s (R, NY-21) then-pending nomination to be Ambassador to the United Nations. If the GOP nominee to replace Stefanik in a special election underperformed by a similar amount, a Trump +21 seat could have been in real danger of flipping. Though TN-7 is probably a less elastic district than NY-21, the two districts had nearly identical results in the last two presidential elections. More broadly, Democrats have been running well ahead of Kamala Harris’s 2024 showing in state legislative specials this year, and Democrats competed for districts with similar profiles in special elections in 2017 and 2018. They actually flipped a district Trump won by nearly 20 points, PA-18, in an early 2018 special election that, like TN-7, paired part of a blue-leaning urban area (Pittsburgh) with much redder rural and small-town areas. We’ll re-rate the seat after the special election—if the GOP wins it would almost certainly be Safe Republican in the context of a general election. But the circumstances of a special election adds a little more uncertainty.

For more color on the TN-7 special election, this walkthrough of the district by Elections Daily’s Nick Morris pairs up well with what we’ve described here.

On the Democratic side of the aisle, there are currently three special elections on the horizon—all of which were prompted, sadly, by member deaths.

The two political parties recently selected their nominees in VA-11, which is basically the “Fairfax County district” in Virginia. James Walkinshaw, who won a multi-way Democratic firehouse primary in large part due to his time working for the late Gerry Connolly (D), will face former FBI agent and veteran Stewart Whitson (R) on Septe. 9. Though Walkinshaw is an overwhelming favorite in this 65%-31% Harris seat, both parties may be looking to the race for hints about the state’s November gubernatorial race.

On Nov. 4, we’ll be watching TX-18, in the Houston area. Though Texas’s use of jungle primaries for special elections adds some intrigue, this seat backed Harris by 40 points, making it the bluest of these districts.

Finally, in between those two elections, we’ll be looking towards southern Arizona, which will hold a special election on Sept. 23. Though the now-vacant AZ-7 backed Harris 60%-38%, her showing in this Latino-majority seat was still 11 percentage points weaker than Joe Biden’s 2020 result. AZ-7’s 20% college attainment rate is also markedly lower than that of TX-18 (29%) and VA-11 (66%).

Primaries in AZ-7 are next week. The Democratic primary, which will be the key race, features three serious contenders. Pima County Supervisor Adelita Grijalva has given few indications that she’d depart ideologically from her late father, Rep. Raul Grijalva (D), who led the Congressional Progressive Caucus for a decade. Her main rivals for the nomination include former state Rep. Daniel Hernandez and activist Deja Foxx, both of whom have gotten outside help from progressive groups. While her opponents are hoping to ride the anti-establishment frustration that has been bubbling up on the left, the compressed timeframe of the election has likely benefitted Grijalva, who has a familiar name and a long track record in local politics. The three-way GOP primary has gotten less attention.

Though we still rate AZ-7 as Safe Democratic, it strikes us as a seat that could have been Likely Democratic if this special election were being held during a Harris presidency. Still, it will be worth watching how this Latino-majority district votes a year after it swung markedly to the right.

See Other Political Commentary by J. Miles Coleman.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.