The Georgia Senate Runoff: The First Shot of 2010?

A Commentary By Rhodes Cook

The 2008 election these days may seem long ago and far away. But it is worth remembering that while the Republicans had a bad time at the polls in November, they fared well in the array of contests that concluded the election cycle in December.

The GOP scored two House wins last month in Louisiana, including the improbable upset of Democrat William Jefferson by a little-known Republican, Anh Cao. The latter became the first Vietnamese-American in Congress. And in Georgia, Republican Sen. Saxby Chambliss scored a decisive victory in a runoff required by state law when he narrowly failed to win a majority of the vote in November.

For symbolic value, Cao's victory was a powerful tonic for a party that had run poorly among virtually all minority groups in 2008. But as a harbinger of the 2010 midterm elections, Chambliss' Senate victory could have much greater import.

Not only did the GOP incumbent expand a 3 percentage point lead over Democrat Jim Martin in the November general election balloting into a 15-point blowout in the early December runoff, but he did so with what was a midterm election-sized turnout.

While nearly 4 million Georgians cast ballots in the presidential voting, only 2,137,956 participated in the Senate runoff. That is nearly identical to the number who cast ballots in the state's 2006 gubernatorial election (2,122,258)--a race that was won handily by Republican Gov. Sonny Perdue. Voter turnout in 2010 will undoubtedly be much closer to these lower numbers than the higher presidential turnout figure.

It can be precarious to draw global conclusions from a single state, yet the Georgia Senate race does give Republicans some hope for 2010 and Democrats a cause for concern. In short, while the latter can turn out their large constituency with Barack Obama atop the ticket, can they do so when he is not on the ballot?

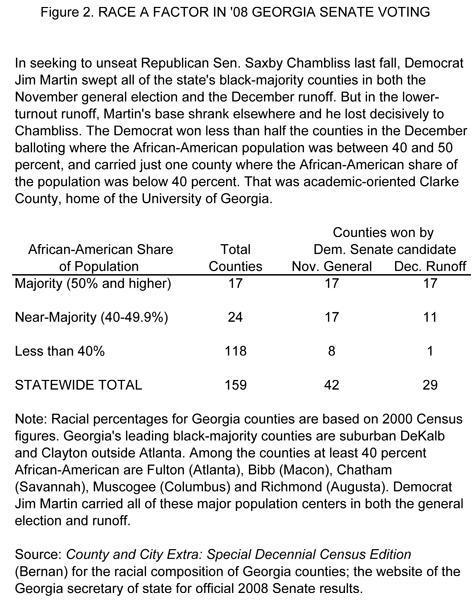

In Georgia, the answer was no. Obama pulled 47 percent of the presidential vote--a losing share to be sure, but the highest for any Democratic presidential candidate in the Peach State since native son Jimmy Carter in 1980. Helped by the outpouring of African-American support for Obama, Martin drew 46.8 percent of the vote, putting him only 3 points behind Chambliss.

But that was Martin's high-water mark. In the runoff, he drew barely half as many votes as he had in November, compared to a falloff of roughly one-third in Chambliss' vote. In a number of populous counties with a significant African-American population, the runoff vote for Martin was less than half as large as Obama's tally a month earlier. Among the counties in this group: Those that include the cities of Atlanta, Augusta, Columbus, Macon and Savannah.

Martin sought to spur Democratic turnout in the runoff by tying himself closely to Obama. He argued that he would be a loyal supporter of the new president, with one flier declaring: "Jim Martin for Senate, Don't Stop With Barack."

But there were no Obama coattails without Obama himself. He sent campaign volunteers to the state, cut a radio ad for Martin, and recorded an automated phone message for the candidate. But conspicuously, he chose not to campaign personally in support of Martin.

Meanwhile, Chambliss brought the Republican ticket of John McCain and Sarah Palin to Georgia to campaign on his behalf, and portrayed the runoff as the first contest of 2010. To Chambliss, the contest was a high-stakes struggle with national importance. If he lost, Democrats would be in position to reach a 60-seat, filibuster-proof supermajority in the Senate if Democrat Al Franken also won his still unresolved contest in Minnesota. If Chambliss won, he could serve as a "firewall" against Democratic excesses on Capitol Hill.

Even under these circumstances, Obama's reticence to get involved was understandable. He was focused at the time on forming his administration. Involvement in the Georgia runoff could have damaged his early moves for bipartisanship. And Democratic victory in the contest was far from certain.

In addition, there was the lesson of Bill Clinton from 1992. Fresh off his presidential victory that year, which included a narrow plurality win in Georgia, Clinton came to the state to campaign for Democratic Sen. Wyche Fowler. Like Chambliss in 2008, Fowler had fallen below the required majority needed to avoid a runoff. But Clinton's involvement did little good. Fowler, who had run ahead in the November voting, was defeated in the runoff by Republican Paul Coverdell. And Clinton lost a bit of his political capital before he was even inaugurated.

Would greater engagement by Obama have made much difference this time? In a state that is still shaded red on the electoral maps, possibly not. But his direct involvement in the runoff would have provided an early test of Obama's ability to offer some coattail pull for Democratic candidates even when he is not on the ballot.

The basic question now is what role Obama will choose to play in the 2010 midterm election. He has quickly assumed the part of commander in chief. Left unanswered is how he will wear his party hat, or more specifically his role as "Democrat in chief."

It may not fit naturally with his bipartisan instincts. And to be sure, how well the Democrats fare in 2010 will in part be determined by how successful Obama and his Democratic congressional colleagues fare at the work of governance.

But the president also must lend a hand in mobilizing the party base to turn out for a midterm election in which he is not on the ballot. And on Obama's ability to do that, the jury is out.

See Other Commentary by Rhodes Cook

See Other Political Commentary

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.