Obama and Reelection: One Term or Two?

A Commentary by Rhodes Cook

When it comes to presidents and reelection, two things seem clear. If they appear to be in control of events, they win. If events seem to be controlling them, they lose.

Often the economy is their top concern, as almost certainly will be the case in 2012. In some elections, it is a foreign crisis or the shadow of a government scandal such as Watergate that drives debate. Yet the basic perception of whether or not the president is a competent leader often determines the political environment in which he seeks reelection.

Embattled presidents—such as Jimmy Carter in 1980 or George H.W. Bush in 1992—usually find their party dispirited or divided, with a significant primary challenger to contend with before the general election. In addition, the weakness of the president often inspires unity in the opposition as they see victory readily attainable.

Yet presidents riding high—such as Ronald Reagan in 1984, Bill Clinton in 1996 and George W. Bush in 2004—often find themselves surrounded by good fortune. Their party is confident and united. The president faces no significant primary opposition. And the other party must frequently search long and hard to find a respectable candidate to run against him.

Where does President Barack Obama fit into all this?

He begins the 2012 election cycle with a presidential approval rating in the Gallup Poll in the vicinity of 50%. Historically, that is pretty good. Recent presidents have been able to win reelection with election-eve job approval ratings as low as 48%, which was where George W. Bush stood a few days before his 2004 reelection.

Obama has gained stature of late. It started with a series of legislative successes during the "lame duck" session of Congress late last fall and continued with his well-received public address following the tragedy in Tucson last month. At this point, the Democratic Party appears united behind Obama's leadership even after severe midterm election losses last November that the president himself termed a "shellacking."

But there are plenty of hot issues on Obama's plate and a feisty Republican House ready to fight him on the issues of the day. In the 22 months ahead, it is anyone's guess whether Obama will join the ranks of embattled presidents or be able to maintain the qualities of a confidently self-possessed leader that he has shown of late.

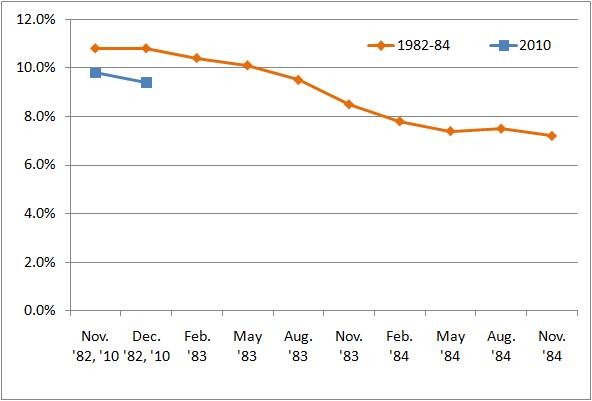

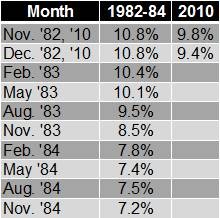

Chart 1. Can Obama Reprise "Morning in America?"

When it comes to dealing with a sluggish economy, the first two years of Barack Obama's presidency have paralleled that of Ronald Reagan's in the early 1980s. In the latter case, the economy began to improve dramatically after the 1982 midterm election, allowing Reagan to successfully campaign for reelection in 1984 on the optimistic slogan: "Morning in America." Will Obama be so fortunate? |

Note: The nationwide unemployment rates here are seasonally adjusted.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Reagan Model

White House strategists would be happy if they could follow the Reagan route to reelection. Like Obama, Republican Reagan inherited an economic crisis when he took office in 1981 that only got worse during the midterm election year that followed. Even with Reagan urging voters to "Stay the Course," the GOP suffered significant losses in 1982 as the unemployment rate approached 11% on Election Day.

After that, though, the economy began to improve. The unemployment rate dropped to 8.3% by the end of 1983, and declined further to 7.2% by November 1984. The brightening financial climate enabled Reagan to successfully run for reelection on the upbeat slogan, "Morning in America."

A byproduct of the favorable political backdrop in 1984 was that Reagan had a clear path to renomination, while Democrats struggled to find a candidate with vote-getting appeal to challenge him.

The Democratic field in 1984 was large but not especially dynamic. The race came down to a choice between former Vice President Walter Mondale, a favorite of the party establishment, and Sen. Gary Hart, who embraced his role as a "new ideas" reformer. With strong institutional support, Mondale won the nomination. But he sparked little enthusiasm at the grass roots and lost decisively to Reagan in the fall.

This time, a large presidential field is forming on the Republican side, drawn—as Democratic contenders were in 1984—by the apparent vulnerability of the incumbent after a difficult midterm election. But unlike many past GOP nominating contests, there is no obvious heir apparent. The closest to the title would be former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, who ran a respectable second to John McCain in the active part of the 2008 Republican primary race.

But nowadays, no Republican really commands top dog status. The party's primary contest begins wide open, a combination of second-time candidates such as Romney and Mike Huckabee as well as an array of untested first-time presidential contenders. One or more may prove to be excellent campaigners. But for now, the GOP race is a rare muddle.

On the Democratic side, there is no sign yet of any primary opposition brewing to President Obama. But it would not need to be a big name opponent—such as Sen. Edward Kennedy was to President Carter in 1980—to make a point. A lesser known candidate could harness latent dissatisfaction with the president should Obama anger the liberal wing of his party in the months ahead. Even a modest-sized anti-Obama vote in the primaries would be an embarrassment to the White House. And it would also show a Democratic Party not as united for the fall campaign as the Obama forces would hope to be.

Yet all these political "what ifs"—a Democratic primary challenge to Obama, an effective Republican challenger, even a potent third party movement in 2012—will largely pivot off his handling of the economy.

To be sure, elements of a recovery are beyond the president's control. But it is the nature of politics that he would receive the lion's share of the credit or the blame regardless of what happens. So, the better the economy is approaching next fall's election, the smoother his path to reelection. In short, it is probably time for Obama to begin channeling his "inner Reagan."

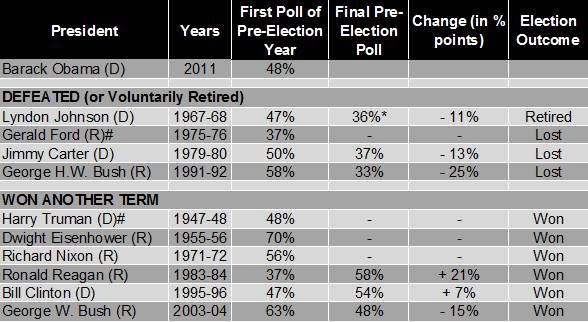

Chart 1. Presidents and Reelection: Approval Ratings Bear Watching

President Barack Obama began this pre-presidential election year with a job approval rating in the Gallup Poll approaching 50%. That is in line with many other post-World War II presidents at a similar point of their presidencies. A number of these presidents, like Obama, saw their party suffer significant losses in their first midterm election and entered the last two years of their initial term with their chances of reelection considered problematic. Ultimately, some went on to win another term; others were defeated – with the outcome often reflecting whether their approval ratings trended upwards or downwards in the nearly two years remaining before the election. |

Presidential Approval Ratings at Beginning and End of Reelection Cycle(Gallup Polls since World War II)

Note: An asterisk (*) indicates that President Johnson's 36% approval score was the last taken before he announced that he would not seek reelection in March 1968. A dash (-) indicates that in 1948, 1956, 1972, and 1976, no presidential approval surveys were taken by the Gallup Poll after August. A pound sign (#) indicates that Presidents Truman and Ford were vice presidents who assumed the presidency after the previous presidential election. In truth, they were not actually running for reelection but for a first full term. So was Lyndon Johnson in 1964, who is not included in this chart because he was not president during the entire election cycle.

Source: Gallup Poll.

Rhodes Cook is a senior columnist at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia

See Other Commentary by Rhodes Cook

See Other Political Commentary

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.