How the House Landscape Changed: A mild decline in competitive seats, and a spike in safe Republican ones

A Commentary by Kyle Kondik

The new House landscape

At long last, the 2022 U.S. House map is complete (we think -- more on this below). So it’s a good time to take stock. The following analysis is based on numbers from Daily Kos Elections (for the old maps in place during the 2020 election) and Dave’s Redistricting App (for the new maps set to be in place for 2022).

Overall, Joe Biden won 226 of the new districts, while Donald Trump won 209. That is slightly up from the old map, which was 224-211 Biden. However, the overall map still has a Republican tint.

A couple of weeks ago, we identified a few districts that were likely to be the “median” House seat by 2020 presidential performance. This is the district right in the middle if we list the 435 new districts in order from where Biden’s margin was the best to where Trump’s was the best. Particularly in an era where presidential voting is strongly correlated with House results, how the median district compares to the nation as a whole can tell us something about the overall partisan skew of the map. The median district is VA-2, a Hampton Roads-based district held by Rep. Elaine Luria (D) that has long been competitive under differing lines. Biden won the district by about 2 points, or about 2.5 points worse than he did nationally (Biden won the national popular vote by about 4.5 points). This mild GOP bias is pretty similar to the median district under the old maps and based on the 2020 results -- that district, held by Rep. Lauren Underwood (D, IL-14), voted for Biden by about 2.5 points (on the new map, Underwood got help from a Democratic gerrymander and saw her district’s Biden margin swell to nearly a dozen points).

There are 215 districts where Biden did as well as or better than his 4.5-point national margin, and 220 where Donald Trump did better. The district most reflective of the nation is the one held by Rep. Sharice Davids (D, KS-3), where the presidential margin was almost exactly the same as Biden’s national showing. Davids held a more Democratic-leaning district on the old map; Republican mapmakers made her district more competitive, and the Kansas Supreme Court allowed it to stand in one of the final notable court rulings concerning the 2022 map.

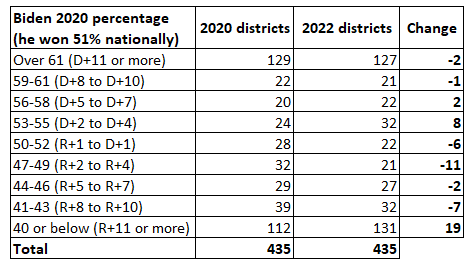

Table 1 shows both the old and the new map sorted by how well (or how poorly) Biden performed in the districts. This is a modified and updated version of a table we included in the Crystal Ball several weeks ago. If you want more detail about how we compiled it, see the explanation in that story. Basically, this uses Biden’s national performance as a baseline and sorts the districts by how much better or how much worse Biden did. The R+1 to D+1 districts are those where Biden got 50%-52% of the vote (rounded to the nearest whole percentage point), the D+2 to D+4 are where he got 53%-55% of the vote, the R+2 to R+4 are where he got 47%-49% of the vote, and so on and so forth. The R+4 to D+4 range is basically what we would consider competitive, although there are exceptions. For instance, if this does end up becoming a Republican wave year, the Republicans could win some seats at the D+5 level or higher; the Democrats could also cut into the R+5 or higher group in a wave year of their own.

Table 1: 2020 Biden performance, old versus new districts

Source: Compiled by author from Daily Kos Elections and Dave’s Redistricting App.

A few things stand out from the table:

-- The total number of competitive districts (as defined by the R+4 to D+4 range) declined from 84 to 75. That’s just 17% of all the House seats, although there are enough competitive seats for there to be big swings from cycle to cycle. Still, one wouldn’t expect all of these seats to be competitive every year: The political environment and the candidates help determine that from year to year. One other thing to remember is that even if every state had a redistricting system designed to incentivize the creation of competitive districts, there still would be scores of uncompetitive races. It’s very hard to draw anything but landslide Democratic seats in many big city areas, for instance, and the same is true for drawing anything other than landslide Republican districts in vast swathes of rural and small-town America.

-- The number of super-safe Republican districts -- those where Biden won 40% or less -- spiked from 112 to 131. One of the drivers of this increase was the Republican gerrymander of Texas, where mapmakers focused on shoring up current Republican seats: The number of seats where Biden received 40% or less increased from 11 to 20 in the Lone Star State (the comparison is slightly skewed because Texas also added 2 extra seats through reapportionment, but the difference is still stark).

-- The number of super-safe Democratic seats, 127, is similar to the Republican total and down slightly from the current maps. Democratic gerrymandering contributed to this slight decline: For instance, Democrats in Nevada reduced the Biden share in Rep. Dina Titus’s (D, NV-1) district from 61.5% to 53.2% in order to shore up 2 other Nevada Democrats. The 3 seats the Democrats hold in the Silver State are now all vulnerable in a Republican wave, although Democrats also should have a better chance to reclaim any lost seat(s) in future elections. Overall, the D+2 to D+4 grouping expanded in size from 24 to 32.

-- The number of Republican seats in the R+2 to R+4 grouping declined, from 32 to 21. Again, Texas is a contributor here. This could help limit Republican damage in a future bad election cycle.

-- There are 211 seats where Biden received 49% of the vote or less, while there are 202 where he won 53% or more. This is another indicator of a Republican edge on the overall map. There are 22 in the middle of the range, the ones where Biden got between 50%-52% of the vote.

The road ahead

A federal court recently ruled that Louisiana’s Republican-drawn map violates the Voting Rights Act, and that the state’s 6-1 Republican map needs to be amended, likely resulting in a 5-2 Republican edge. However, a similar ruling throwing out Alabama’s map was stayed by the U.S. Supreme Court, leaving Alabama’s map in place for at least 2022. Something similar seems likelier than not to happen with this Louisiana ruling, although this is one piece of outstanding business that hypothetically could impact the 2022 map.

As we look beyond 2022, remember that maps can change throughout the decade. There is no federal prohibition on mid-decade congressional redistricting, although some states do prohibit it.

The most famous recent example of a mid-decade remap that was not prompted by court action was in Texas following the 2002 election. Prior to that election, Republicans controlled the Texas governorship and state Senate, but Democrats held onto the state House. A court-ordered congressional map helped effectively preserve a previously-drawn Democratic gerrymander from the 1990s, which aided Democrats in retaining a small edge in the state’s House delegation despite Texas’s clear movement to the right in that era. Republicans took the state House in 2002, and the newly unified Republican state government drew a new gerrymander that favored them. Texas Republicans have continued to gerrymander the state even as the state has become more competitive in recent years (although the state still clearly leans to the right overall). Republicans attempted a gerrymander in Colorado following 2002 as well, but state courts decided that state law only allowed for one remap per decade. We bring this up only to say that maps may change later this decade, both because of state legislative action or state or federal court action.

For instance, North Carolina appears very likely to have a new map next cycle, as a court-imposed map is only set to be in place for this cycle. It is quite possible that North Carolina Republicans will once again have the power to gerrymander aggressively: They could flip control of the state Supreme Court -- it is 4-3 Democratic now and has stymied GOP gerrymandering the past couple of cycles -- and replace the current map, which has 7 Trump-won and 7 Biden-won districts, into something considerably more lopsided (perhaps 10-4 or even 11-3 Republican).

Ohio’s map could be thrown out as a Republican gerrymander sometime this calendar year, which could perhaps help Democrats in 2024, but much is uncertain, and the state’s Supreme Court composition could change in a way helpful to Republicans this November. Ohio’s new -- and, it must be said, failed -- redistricting system was designed to foster bipartisan cooperation in creating maps that would endure throughout the decade. It did not work, and the state could very well have multiple congressional maps this decade; at some point, Republicans may get a durable 13-2 map, although they also could win a 13-2 edge on the map in place for this year.

There are a lot of moving pieces here, but it is possible that the present Republican edge on the overall U.S. House map could grow over the course of the decade because of fresh GOP gerrymanders, most likely in North Carolina. However, there could also be developments that end up helping Democrats, and changes in voting patterns will alter how some of these districts perform in the coming years.

Looming over all of this is the possibility that conservatives on the U.S. Supreme Court could embrace the so-called “independent state legislature” doctrine,” which could have important electoral consequences, including effectively preventing state courts from exercising oversight over congressional redistricting. If the court embraced this theory, it could hypothetically prevent state courts from acting as a check on state legislatures in the congressional redistricting process, which has become more common in recent years, helping Democrats in states like North Carolina and Pennsylvania and, this cycle, Republicans in Maryland and New York. Such a ruling could even force the dissolution of independent redistricting commissions, under the premise that redistricting power can only lie in the hands of state legislatures. This is all a hypothetical at this point, but we thought it merited mentioning as an important potential development in the near future (this theory could also effectively allow state legislatures to override the will of the voters in appointing presidential electors, as conservative former federal judge J. Michael Luttig warned a couple of months ago).

The bottom line for now is this: For all of the twists and turns of the redistricting cycle, the map that will be in place for 2022 is pretty similar to the one in effect in 2020: a bit better for Republicans than Democrats, but not dramatically so. Republicans continue to be strongly favored to win the House this year, and that has much more to with the political environment than the maps. The overall House map is balanced enough that the majority could flip to Republicans in 2022 but back to Democrats in a future cycle, although the playing field is almost certain to change following this election.

A bit about New Hampshire, and our overall House ratings

As noted above, the final state to approve congressional maps was New Hampshire.

The reason it took so long was because of an intraparty dispute. State legislative Republicans wanted to change the map to make it easier for Republicans to win the state’s eastern district while making it easier for Democrats to hold the state’s western district. Democratic Reps. Annie Kuster (NH-2) and Chris Pappas (NH-1) currently hold, respectively, the state’s western and eastern districts. Any move to make NH-1 more Republican would make NH-2 more Democratic, given that there are only 2 districts. Gov. Chris Sununu (R-NH) didn’t want to change the districts, arguing that they were both competitive as drawn and that Republicans could win them both this year. With the governor and the state legislature unable to come to an agreement, the state Supreme Court adopted a new map that barely changed anything -- meaning that Sununu got his way.

Biden won Pappas’s NH-1 by about 6 points and Kuster’s NH-2 by 9. We’re going to start NH-1 as a Toss-up and NH-2 as Leans Democratic. We essentially agree with Sununu: Republicans could end up winning both districts this cycle, although we’ll give Kuster a bit of the benefit of the doubt to start. She hasn’t had a truly difficult reelection bid since beating now-former Rep. Charlie Bass (R, NH-2) in 2012, which was a rematch from 2010, although her margins have ranged from about 4.5 points to the low double-digits. Sununu has backed moderate Keene Mayor George Hansel (R), although there is a more conservative candidate running as well, former Hillsborough County Treasurer Robert Burns (R). We can imagine this being a Toss-up later in the cycle, particularly if Hansel proves to be a good candidate and wins the September primary (we would say the same about the state’s U.S. Senate race, where Democrat Maggie Hassan is seeking a second term against unheralded opposition -- the Granite State can swing a lot in waves). Pappas, meanwhile, could face a rematch with 2020 Republican nominee Matt Mowers, who was just endorsed by the top 2 House Republicans, Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R, CA-23) and Minority Whip Steve Scalise (R, LA-1). Mowers faces others in his primary, though, and suffered through an embarrassing headline when it was revealed that he voted in 2 different states during the 2016 presidential primary.

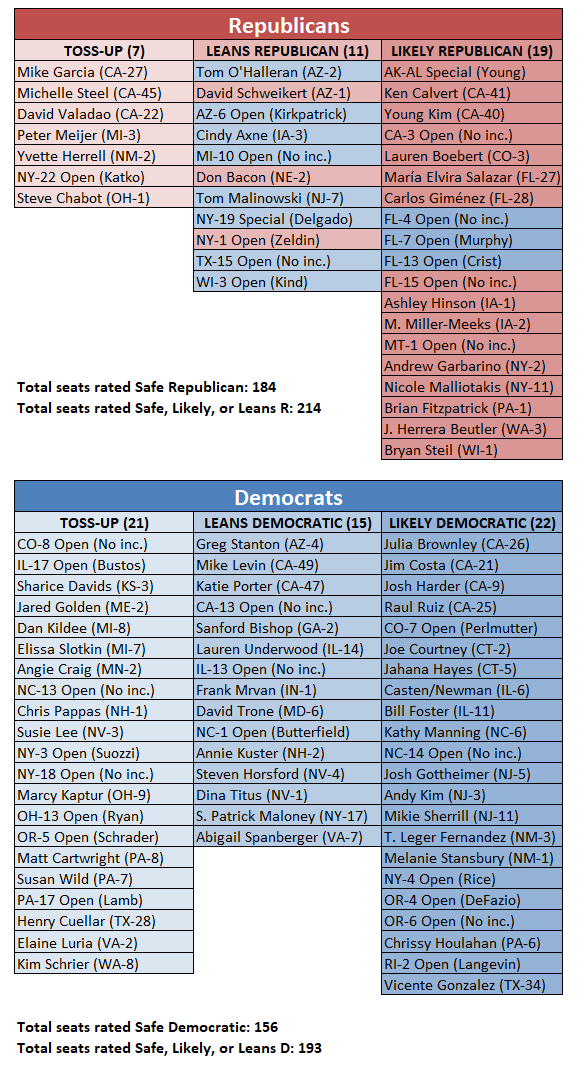

With the House map now apparently complete, we are reverting back to our traditional House rating table for the rest of the cycle, which is shown below as Table 2. The rating table is also available on the House page on our Crystal Ball website. This table only lists races rated as Likely Democratic or Republican, Leans Democratic or Republican, and Toss-up. We’ve added a little more information to the tables, including the number of districts rated Safe for each side. Our ratings currently show 214 races at least leaning to the Republicans, 193 at least leaning to the Democrats, and 28 Toss-ups -- a clear edge for Republicans.

Table 2: Crystal Ball House ratings

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.