Three’s Company

A Commentary By Larry J. Sabato and Kyle Kondik

Who will join the Democrat and Republican on 2016’s presidential ballot?

Republican presidential polling leader Donald Trump signed a pledge earlier this year agreeing to support the eventual GOP nominee, but that agreement is certainly not legally unenforceable. If Trump wants to run as a third-party or independent candidate, there’s nothing stopping him. Trump is aware of this: The weekend before Thanksgiving, he retreated to his pre-pledge position, saying that he needs to be “treated fairly” by the GOP in order to rule out an independent bid. Some senior Republicans naturally wonder if the only outcome Trump will regard as fair is his installation as the party nominee.

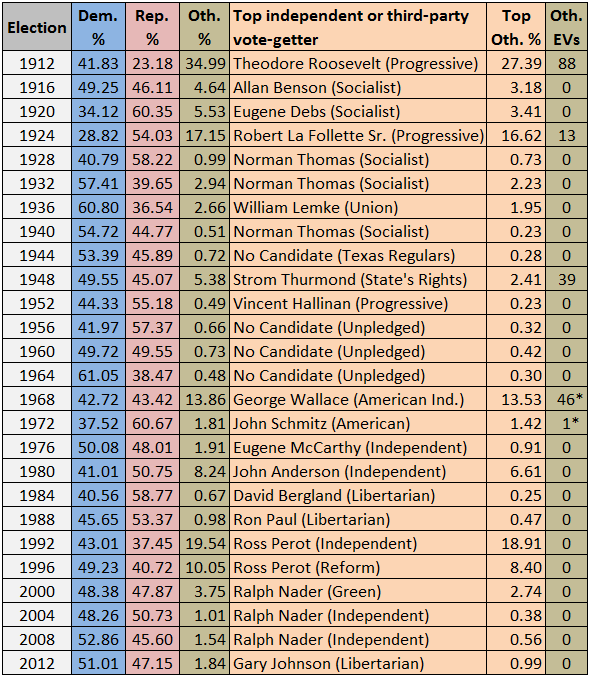

Any list of prominent third-party possibilities has to start with Trump, and not just because the flamboyant billionaire could hypothetically fund such a campaign (although he still hasn’t put that much of his own money into his current effort and has run the nation’s first, free Twitter-based campaign). While presidential campaigns always feature more than just the two major party nominees, some years the non-Republicans and non-Democrats only get a few votes, while in other years they win several percentage points or more. If he ran as an independent it’s possible that Trump could be in the latter category, in part because he is in some ways similar to the two most successful third-party candidates of the past half-century: George Wallace and Ross Perot.

Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama, ran on a platform of law and order and white grievance in 1968 and got 13.5% of the vote — after having soared as high as the mid-20s in some polls. Wallace was the last third partier to win a state: He captured five Southern states and came close to denying Richard Nixon an Electoral College majority. This circumstance likely would have made Hubert Humphrey president because the Democrats solidly held the House of Representatives, which picks the president if no one gets a majority (with each state delegation getting a single vote).

In 1992 Perot, a Texas businessman, was a populist who ran against free trade, national deficits, and political gridlock. Perot outdid Wallace in some surveys, actually reaching the 40% level in June. In November, he didn’t win any states, but 18.9% of the electorate chose him to go to the White House. (Four years later, in Perot’s second and final run, he fell to 8.4%.)

Neither Wallace nor Perot were true economic conservatives. Wallace was a Southern populist willing to use tax money for middle and working class needs, and while a deficit hawk, Perot was against tax cuts that added to the national debt. At the very least Wallace and Perot were to the left of the current Republican economic consensus, which is precisely where Trump’s economic policy lies. Trump pulls from the platforms of both Wallace and Perot, and there’s a sizable audience for this approach. In the 1970s, Oakland University sociologist Donald Warren called the audience “Middle American Radicals,” or MARS, voters who are suspicious of both big government and big business and who feel that government helps the rich and the poor but not the middle class. John B. Judis wrote a fascinating piece for National Journal recently about how Trump, like Wallace and Perot before him, has activated these voters, who generally have low-to-mid levels of income and education. Pat Buchanan, who sought the GOP nomination in 1992 and 1996 and won New Hampshire in the latter, was another MARS-aligned candidate.

While Perot most likely took from both Bill Clinton and President George H.W. Bush in 1992, Trump’s role as a third-party candidate in 2016 might be more akin to Wallace’s, except he could succeed where Wallace failed in denying the Republicans the White House.

But let’s turn this around: What happens if Trump is the Republican nominee? Could that create a deep GOP split and a third-party run by a “true” Republican?

Perhaps an establishment Republican running under the “Real Republican Party” flag or some other hastily-organized third-party banner could be an alternative for moderates and conservatives who cannot vote for Trump. While the other Republican presidential candidates signed the same symbolic loyalty pledge to the party nominee that Trump signed, we are already hearing that some prominent Republicans would oppose Trump if he were the party’s nominee. Perhaps one of them could run for president.

We have been reliably told that a fair number of Republican governors and U.S. senators would either sit on their hands entirely or simply issue a paper “endorsement” of Trump, should he be crowned in Cleveland next summer. Maybe that is just bold and premature talk, or perhaps it is real. After all, much the same thing happened in 1964, when Barry Goldwater captured the Republican presidential nomination to the dismay of the GOP establishment. Prominent Republican governors such as Nelson Rockefeller of New York, George Romney of Michigan (father of Mitt), and Bill Scranton of Pennsylvania had little time for Goldwater, as did dozens of GOP members of Congress hoping to hold on in November. While none mounted a third-party bid in 1964, it is not impossible that a senior officeholder will do so in 2016 — not so much with hopes of winning but rather to send a message about what the Republican Party’s future should be. The odds are against it, yet nothing can be preemptively ruled out in an election that is already one of the wildest in modern history.

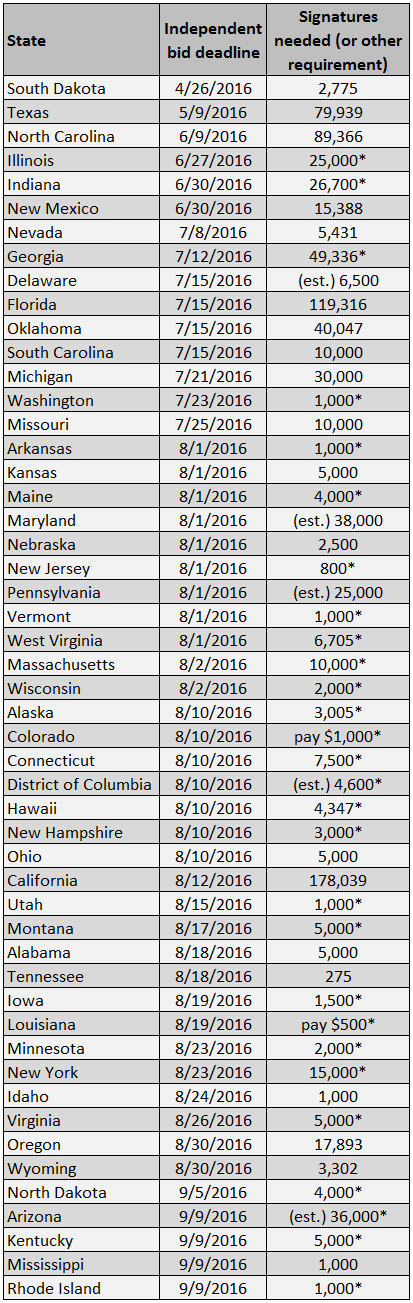

The calendar will help to determine whether there’s a truly prominent third-party candidate on the ballot. Filing deadlines for independent presidential candidates vary by state, but a majority fall in August. That is after the conventions — 38 states’ deadlines are after the RNC ends on July 21 — but not so far after them that a spurned candidate could easily turn around and get on many state ballots. A candidate who wants to get on every ballot will have to start much earlier than that: For instance, the deadline for an independent to get on the ballot in Texas, the second-biggest state, is May 9. So maybe it would be helpful to the Republicans if Trump hangs around in the primary — so long as he doesn’t win the nomination — just long enough for a national third-party bid to be out of reach.

Table 1: Independent filing deadlines by date and ballot access requirements

Notes: *Indicates that a state permits an independent candidate to use a partisan label on the ballot (other than “independent”). Some signatures requirements are estimates.

Source: Ballot Access News, November 2015 issue

What we do know is that there will be other options for voters besides the two major-party nominees, although at the moment the likeliest non-major-party candidates are quite minor.

Of the roughly 1,400 people who have filed with the Federal Election Commission as presidential candidates, fewer than half are Democrats or Republicans. Nearly all of these candidates will put no effort into their self-styled campaigns, but a few will. The Green Party’s Jill Stein, who ran in 2012, is running again. She won 0.36% of the vote last time. The most prominent 2012 third-partier, Libertarian Party nominee Gary Johnson, won about one percent nationally. Johnson, a former Republican governor of New Mexico who ran for president as a Republican during the 2012 cycle before launching his third-party bid, also says that he plans to run again in 2016 although he has not yet filed with the FEC.

While the last three presidential campaigns have featured only minor third-party campaigns, there have been several prominent ones over the last century. Perhaps the most famous and impactful was Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive “Bull Moose” splintering of the Republicans in 1912. Roosevelt finished ahead of GOP President William Howard Taft nationally, allowing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to easily capture the White House despite winning just 41.8% of the national popular vote. Roosevelt’s popular-vote performance — 27.4% — is the best of any non-Democratic or non-Republican nominee since 1856, the first year both parties had a presidential nominee.

Throughout the early part of the 20th century, the Socialist Party nominee (often Eugene Debs) would get a few percentage points worth of the vote, with 1912 marking the Socialists’ high-water mark (Debs got 6.0% in that fractured election). The next major third-party insurgency was in 1924, when Sen. Robert La Follette Sr. of Wisconsin, a Republican running under the Progressive Party banner, got 16.6% nationally and won his home state. La Follette also finished second in several western and Midwestern states, ahead of the weak Democratic nominee, John W. Davis; overall, Republican Calvin Coolidge easily won the election.

President Harry Truman’s historic come-from-behind victory in 1948 featured two notable third-party candidates: State’s Rights segregationist Strom Thurmond, who squeezed Truman from the right and won four Deep South states, and Progressive ex-Vice President Henry Wallace, who pressed Truman from the left though he failed to win any states. Thurmond and Wallace split about 5% of the national popular vote.

George Wallace and Ross Perot’s third-party efforts are discussed earlier. Two others worth mentioning are John Anderson’s independent run as a moderate Republican in 1980 and Ralph Nader’s Green Party effort in 2000. Anderson won 6.6% in 1980, though he took votes about evenly from winner Ronald Reagan and losing incumbent Jimmy Carter. Anderson’s showing was “an underrated marker on the country’s road towards its current political geography,” the New York Times’ Nate Cohn recently argued. Anderson did much better in the North and West than the South, and some of the places where he did well, like New England, are more Democratic now than they were back then (see Cohn’s map of Anderson’s performance). In 2000, it is almost certain that Nader, who won 2.7% nationally, prevented Al Gore from winning Florida and probably New Hampshire as well, either of which, if flipped, would have given Gore the White House. Gore lost Florida by just 537 votes while Nader got 97,488 statewide, and Nader’s 22,198 Granite State votes were about three times George W. Bush’s 7,211-vote plurality there. The point here isn’t to re-litigate the contentious 2000 race; it is merely to point out that Nader’s third-party bid had a decisive impact on its outcome.

Table 2: Independent and third-party performance, 1912 to 2012

Note:*In 1968, one faithless elector in North Carolina cast his vote for George Wallace rather than Richard Nixon. In 1972, one faithless elector in Virginia cast his vote for Libertarian John Hospers rather than Nixon.

Source: Dave Leip’s Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections

There are other possibilities for independent or third-party candidacies, ones that might hurt Hillary Clinton in November. Former Sen. Jim Webb (D-VA) withdrew from the current Democratic contest and suggested he might well end up on the ballot as an independent. In a close election, a la Nader, Webb could draw critical votes from Clinton. Webb straddles party lines on some issues (such as gun control and defense) but it is difficult to imagine many Republicans migrating to his banner — unless the GOP nominates Trump or perhaps Ben Carson or Ted Cruz. Webb would try to occupy “middle ground,” though in this era of strong partisan polarization, the middle of the road is merely a six-inch wide yellow line where you get hit from both sides.

Or how about former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg? His positions on social issues are equally, if not more, liberal than Clinton’s, and Bloomberg is a billionaire with a willingness to do what the more miserly Trump has not — spend freely to win an election. Bloomberg certainly wouldn’t do Clinton any good and could cost her the election under the right set of circumstances. However, he has shown no sustained interest in such a candidacy as yet. Maybe a Clinton-Trump or Clinton-Cruz matchup would draw him into the race.

Finally, while we are speculating with abandon, we might as well throw in California Gov. Jerry Brown (D-CA), the Democrat who is in his fourth and last term as chief executive of our nation-state. Brown has thrice run for president (1976, 1980, and 1992), and no one that ambitious could possibly get the urge to run completely out of his system. If Brown saw an opening — say, a weakened, wounded Hillary Clinton and an extremely controversial GOP candidate headed for summer nomination — might he not give the White House one more try? In addition, Brown ran against Bill Clinton in 1992 in a testy primary season; while there is no ongoing feud with the Clintons, it is fair to say there isn’t an excess of mutual admiration between them either. It’s true that Brown would be 78 years old by Inauguration Day 2017, but is age a compelling issue anymore? Ronald Reagan left office at 77, and both Bob Dole in 1996 and John McCain in 2008 were in their 70s when they were GOP presidential nominees. Hillary Clinton will be 69, Sanders will be 75, and Joe Biden will be 74 at swearing-in time. Nowadays, a respected, relatively youthful vice presidential candidate would suffice as an acceptable insurance policy for most Americans.

Whew! That got fanciful, didn’t it? We’re just about out of extremely improbable scenarios. Nonetheless, at this early point, given the explosive environment developing around the 2016 election, no one should be surprised at anything. We didn’t even mention the possibility of a wealthy celebrity deciding to take the plunge. Will Smith has been making noises about a candidacy for an unspecified office. Clint Eastwood and Arnold Schwarzenegger are free and available, having already served terms in California posts (though Schwarzenegger, who is not a natural-born citizen, would need a constitutional change to run for president). And Kanye West, who has all but announced for the White House in 2020, could move up his plans by four years.

Are these things any stranger than the TV host of The Apprentice becoming the Republican presidential frontrunner? Not really, not in 2016.

Larry J. Sabato is the director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia.

See Other Political Commentary by Larry Sabato

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik

See Other Political Commentary

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.