Notes on the State of the Senate

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik

GOP remains favored to hold the majority overall.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— Senate retirements are not having a dramatic effect on the partisan odds in any race so far.

— Democrats have missed on some Senate recruits, and that may (or may not) matter in the long run.

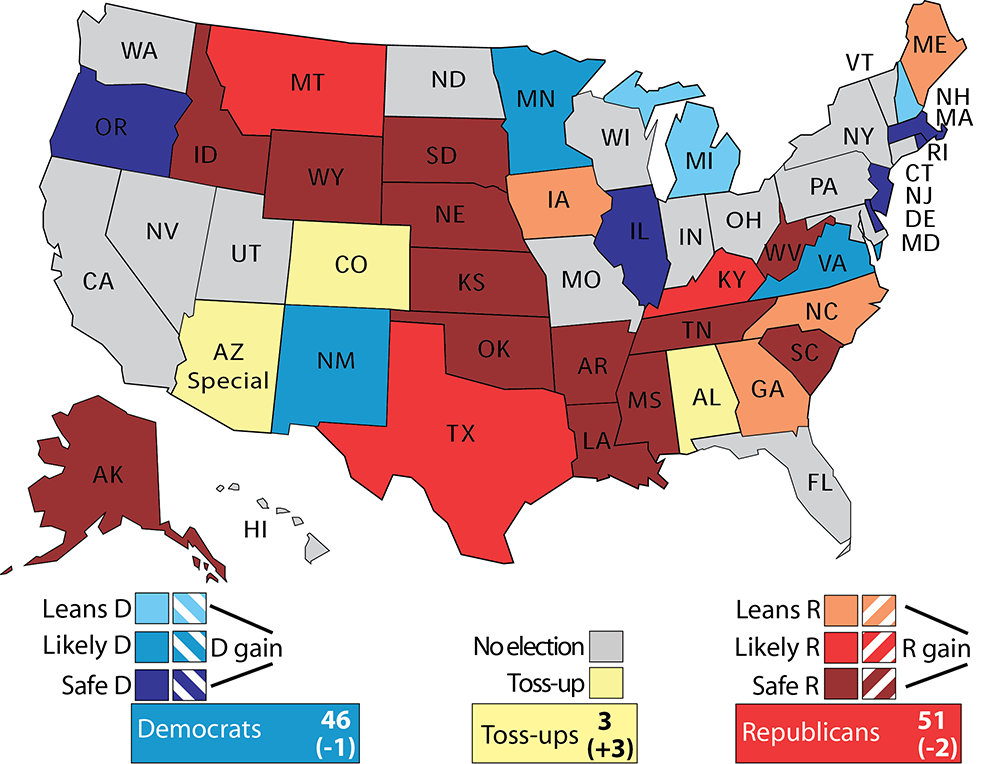

— Alabama and Colorado remain the likeliest states to flip, with the Democratic-held Yellowhammer State the likeliest of all.

— Arizona is the purest Toss-up.

— Republicans remain favored overall.

Notes on the battle for the Senate

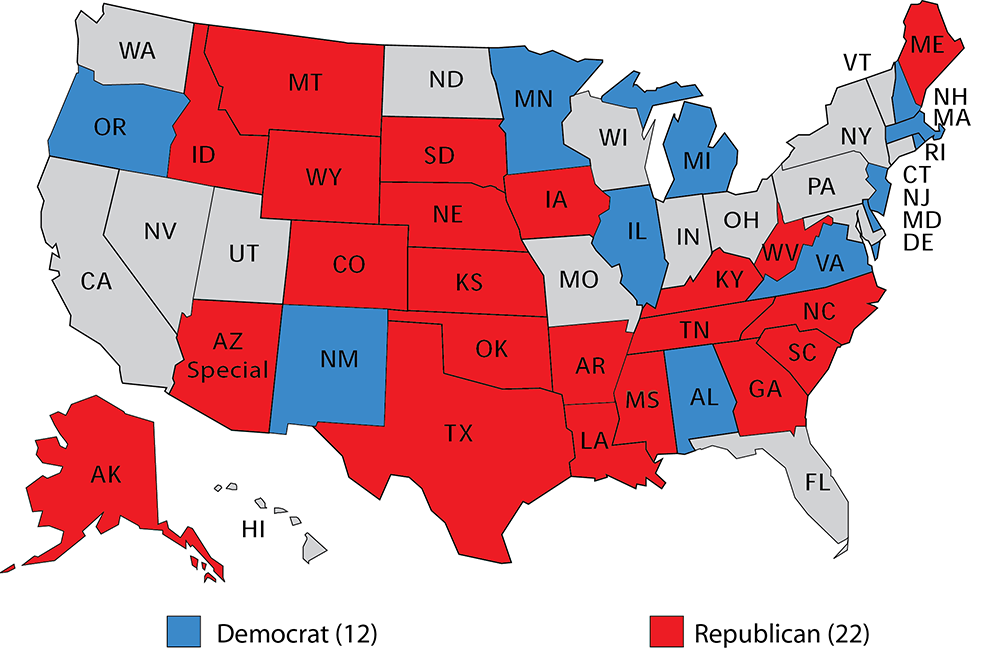

Republicans have to defend 22 Senate seats this cycle to the Democrats’ 12, yet the GOP remains favored to hold the chamber in large part because so many of the seats they are defending are in states that seem certain to vote Republican for president, and strongly so.

Map 1: 2020 Senate races, shaded by incumbent party

Map 2: 2020 Crystal Ball Senate race ratings

Of the 22 seats that the Republicans are defending, 15 are in states that Donald Trump won by 14 points or more in 2016. The overall Senate balance of power is 53-47, meaning Democrats would need to net, at minimum, three seats to take the majority (the vice president elected in 2020 would break a 50-50 tie).

What follows is a status report on the race for the Senate, divided into five storylines we’re following so far:

1. Retirements are not having a dramatic effect on the partisan odds in any race so far. Retirements often play a crucial role in the Senate calculus because even though the power of incumbency is waning, one still would expect a normal incumbent to perform better than a non-incumbent. As an example, while Democrats lost four states held by incumbents last year, they almost assuredly would have lost dark red Montana and West Virginia, too, had Sens. Jon Tester and Joe Manchin not run for reelection in their respective states.

Retirements also can be important mile markers on the road to the general election: For instance, the Crystal Ball deemed the surprising retirement of Sen. Olympia Snowe (R-ME) in late February 2012 as a “Snowepocalypse” for the GOP that greatly harmed their chances of flipping the chamber. Independent Angus King ended up winning the seat under the assumption that he would caucus with Democrats (he did, and has ever since), and Republicans’ initial bullishness about winning the Senate waned (Democrats netted two seats that year, somewhat surprisingly). The following cycle, Sens. Tom Harkin (D-IA), Carl Levin (D-MI), Max Baucus (D-MT), Tim Johnson (D-SD), and Jay Rockefeller (D-WV) all announced their retirements by the end of April 2013, an early signal that the Democratic majority was in deep trouble (Republicans would end up winning all but Michigan as part of a net nine-seat gain that gave them a 54-46 majority).

At least four of the 34 Senate races this year will feature open-seat races next year. But unlike the retirements in 2012 and 2014, this group of retirees doesn’t tell us much about what to expect next year.

The retirees are Sens. Tom Udall (D-NM), Pat Roberts (R-KS), Lamar Alexander (R-TN), and Mike Enzi (R-WY). The three Republicans are all from very Republican states, so we kept all three races as Safe Republican. We saw last year, in another open-seat Tennessee race, that the Democratic cause there seems hopeless, given that a strong Democratic candidate in a good Democratic election year, former Gov. Phil Bredesen, couldn’t even get within single digits of now-Sen. Marsha Blackburn in the race to replace now-former Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN). Wyoming hasn’t elected a Democratic senator since 1970 and is arguably the most Republican state in the nation. Kansas hasn’t elected a Democratic senator since 1932; Senate Republicans apparently are ready to campaign against Kris Kobach (R), the party’s weak 2018 gubernatorial nominee, if he jumps in the race. If Kobach does enter the race we may need to change Kansas’ rating, but at this point we do not see it as a realistic Democratic target given its long and enduring GOP leanings.

New Mexico, while the most competitive of these four states, is still trending Democratic. We moved that race from Safe Democratic to Likely Democratic, but only out of an abundance of caution.

In other words, at this point it appears that the most vulnerable incumbents on both sides are still running, at least for now. Just as in 2012, when Snowe’s retirement gave the Democrats a seat they otherwise would’ve had little chance to win, Maine features the most important candidate decision, as Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) is a significantly stronger candidate than any replacement Republican would be. Collins said earlier this year that she intends to run for reelection, though.

2. Chuck Schumer has struck out on some of his recruiting targets. An early story of the race for the Senate involves those Democrats who have decided not to run for the Senate. Former Gov. John Hickenlooper of Colorado, Gov. Steve Bullock of Montana, and former Rep. Beto O’Rourke of Texas all opted for the presidential race instead of Senate contests in their respective states. Stacey Abrams of Georgia, who lost a close gubernatorial race in 2018, also took a pass and may still be mulling a presidential bid. Former Gov. Tom Vilsack and first-term Rep. Cindy Axne, both of Iowa, also decided against Senate bids.

It does seem fair to say that if it was just up to Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY), many or all of these candidates would be running. Obviously, it’s ultimately not up to him, and the number of major Democrats who have said no to running for the Senate has led to questions about the ability of Democrats to win the chamber.

It’s natural for the leadership of both parties to gravitate toward candidates who have higher levels of name ID and more proven ability to raise money and run a credible race. That said, we agree with Nathan Gonzales of Inside Elections, who recently wrote that it’s far too early to judge the eventual Democratic Senate slate. Republicans faced some questions about their candidates this time a half-dozen years ago, and they ended up doing quite well. It’s also unclear as to whether the aforementioned names actually are the best candidates in their respective states. Maybe a candidate such as Teresa Tomlinson (D), the former mayor of Columbus, GA who is seeking the Georgia Democratic nomination, would actually be a better fit than Abrams, who never seemed very interested in a Senate bid anyway.

Republicans also don’t have a perfect record of candidate recruitment as they try to put some Democratic seats in play. Gov. Chris Sununu (R-NH) recently announced that he’s going to run for a third, two-year term as opposed to challenging Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), meaning that Republicans will have to find a different and almost certainly less proven challenger. Additionally, there is an odd recruitment story unfolding in Michigan, which along with Alabama is the only Trump-won state Democrats are defending in this cycle’s Senate elections. With Sen. Gary Peters (D-MI) seeking a second term, many Senate Republicans hope that Iraq veteran John James (R) runs again after his credible albeit unsuccessful challenge to Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-MI) last cycle. But the Trump reelection campaign may be actively dissuading James from running, based on the thinking that “a statewide campaign by James could force Democrats to spend more money in the state, driving turnout on the other side and potentially hurting the president,” as Politico‘s Alex Isenstadt reported. Perhaps the Trump camp hopes that Democrats will take Michigan for granted, as Hillary Clinton’s campaign seemed to do for much of the 2016 cycle. But one would think the Democratic presidential campaign is going to expend maximum effort in Michigan regardless of the Senate race, as the state seems necessary (at least to us) for a Democratic presidential victory. From that standpoint, it might make sense for Republicans to field the strongest possible slate of candidates in Michigan, which very well might include James. That’s what the National Republican Senate Committee believes, as evidenced by a recent NRSC memo arguing for James to run for Senate obtained by the Washington Post.

3. Alabama and Colorado remain the likeliest states to flip. Speaking of candidate recruitment, the eventual challengers to Sens. Doug Jones (D-AL) and Cory Gardner (R-CO) remain unknown, and we characterize both of their races as Toss-ups. After all, there’s always the possibility that the challenging party will nominate a dud opponent against either, as Republicans did in the 2017 special election won by Jones, who beat the disastrously flawed Roy Moore (R).

However, assuming decent challengers, both Jones and Gardner are quite vulnerable (Jones in particular given how red Alabama is in a presidential year). Gardner could run ahead of Donald Trump in Colorado, something he probably will have to do to win unless Trump does significantly better in Colorado than he did in 2016 (he lost the state by about five points). In that respect, Gardner may be at the whim of forces he does not control, although Colorado isn’t nearly as far gone at the presidential level for Republicans as Alabama is for Democrats.

In an age where ticket-splitting has become much less common, the individual attributes of the incumbents — and the challengers — may not mean as much as they commonly have in the past. For that reason, it’s far from guaranteed that Jones could win even if Moore ran and got the nomination again; despite Moore’s horrible baggage and campaign, he only lost to Jones by less than two points.

4. Arizona is the purest Toss-up. Arizona seems an odd fit as a swing state: It is in some ways an outpost of the conservative Deep South, at least in terms of some of its early migration and party identification patterns (Arizona after statehood was dominated by conservative Democrats, just like the old Solid South). If Ronald Reagan is the father of modern conservative Republicanism, then Arizonan Barry Goldwater is its grandfather. And yet, Arizona came within 3.5 points of backing Hillary Clinton in 2016 and, two years later, it elected a Democratic senator for the first time in three decades.

The Democrats’ hopes of winning a Senate majority in 2020 hinge, to a large extent, on Arizona electing a second Democratic senator. Arizona hasn’t had two Democratic senators at the same time since Senate Majority Leader Ernest McFarland (D-AZ) lost to Goldwater in 1952 (which opened the position of Senate Democratic leader to Lyndon Johnson, whose party would retake the majority two years later). 1952 also was the first year that Arizona clearly started voting to the right of the nation in presidential elections. It still does, albeit not as sharply if 2016 is any indication. We rate the race for both Arizona’s 11 electoral votes, and its 2020 Senate race, as Toss-ups. History suggests we’re being overly kind to Democrats, but time will tell and there are some hopeful trends for Democrats there.

A common refrain from our Republican Senate contacts throughout the 2018 cycle was that outside Republican groups held their fire for too long against now-Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ), allowing her to build up a positive image during her unopposed primary while the Republicans slogged through their own. Sinema ultimately was able to withstand negative attack ads about her past — in which she expressed opinions that were considerably to the left of where she positioned herself as a Senate candidate — and she beat Martha McSally (R) by a couple of points. Now McSally is back on the ballot, this time running as an appointed senator for the remaining two years of the late John McCain’s term. Democrats have rallied around Mark Kelly, a former astronaut who is married to former Arizona Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D). Kelly has gotten off to an astounding fundraising start and is a newcomer to formal elective politics. His candidacy represents a recruiting success for Senate Democrats, as does the decision by Rep. Ruben Gallego (D, AZ-7) to pass on a bid, clearing Kelly’s path to nomination. Kelly looks great on paper, but we’ll have to see how he performs. Republicans, hoping to muddy Kelly’s reputation early in the race, have started attacking him over some of his past paid speeches. Whether the attacks stick or not, Republicans don’t want Kelly to get the early, positive head start that some of them believe Sinema got last cycle.

If McSally is nominated again and wins, she’ll presumably run for a full, six-year term in 2022, meaning that she might end up being her party’s Senate nominee in three straight election cycles: 2018, 2020, and 2022. That would be a rare feat, although it’s not without recent precedent. Former Sen. Scott Brown was a Republican nominee in three straight Senate cycles, winning in an early 2010 Massachusetts special election, losing to challenger Elizabeth Warren (D) for a full Massachusetts term in November 2012, and then losing as the GOP challenger to Shaheen in New Hampshire in 2014. That said, McSally would be running in the same state, and in the November election each time, if she is in fact the GOP Senate nominee in 2020 and 2022, so the comparison to Brown isn’t a perfect one.

5. Republicans remain favored overall. Arizona looms so large because it’s hard to really piece together a plausible path to a Democratic majority without it flipping. If one assumes that Democrats lose Alabama but win Colorado — the former is a better assumption than the latter — that evens out to no net change. So even if Democrats win Arizona and Colorado but lose Alabama, they would need at least two more victories in GOP-held seats. Which ones? The list actually isn’t that long, or that appealing, for Democrats.

Beyond Colorado, Republicans are defending only one other seat in a state that Hillary Clinton won in 2016: Maine, where Collins is on track to run for a fifth term. Collins does not appear to have a top-tier Democratic challenger as of yet — here’s another place where Democrats have recruiting work to do. We also haven’t seen much compelling data that indicates Collins is truly vulnerable despite her important role in Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation last fall, although of course she might be.

Other Democratic possibilities are Georgia, Iowa, and North Carolina; the Tar Heel State may be the best target of that trio, given its history of close Senate races and because it was the closest of the three states in the 2016 presidential race. Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) also now faces a primary challenger. If Trump tanks in 2020, Democrats could end up carrying all three states for president as part of a larger national sweep that wins them unified control of the presidency and Congress. If Trump wins, or even if he loses narrowly, he likely will carry all three of these states, providing a buffer for their GOP Senate incumbents.

Barring some other big upset (Texas?), Democrats probably won’t win the Senate without at least one of Georgia, Iowa, or North Carolina.

Winning one or more of those is possible for Democrats, but none of them looks like a true Toss-up right now. That, plus the reality that even more plausible targets like Arizona and Colorado are far from sure things, helps illustrate why Republicans remain favorites to retain the upper chamber.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary.

This article is reprinted from Sabato's Crystal Ball.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.