Democrats Hope For A Nationalized Virginia Election This Fall

A Commentary By Kyle Kondik

Richmond chaos could threaten state legislative takeover but big-picture trends still favor team blue.

KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— The crisis in Richmond involving the state’s top elected Democrats continues, and the ultimate resolution remains unclear.

— Democrats will be trying to win the state House and Senate this November. The election will provide a good test of what really matters: local or national factors.

— Virginia is the only state where the party that did not win the state in the 2016 presidential election nonetheless controls both chambers of the state legislature.

— A Democratic state legislative takeover might produce the most liberal state government in the modern history of the South, while also setting Virginia apart from the rest of the region.

For Virginia Democrats, the agony of the moment mixes with the promise of the future

The still-unfolding political crisis in Virginia threatens to derail what could be a breakthrough moment in the South this November for modern Democrats, although it also provides a test of nationalization versus localization that could still break in the Democrats’ favor.

We released a special edition of the Crystal Ball last Tuesday afternoon (Feb. 5) dealing with the crisis in Virginia. Since then, there have been several new developments. Last Wednesday, state Attorney General Mark Herring (D) admitted to once appearing in blackface by imitating rapper Kurtis Blow when he was a University of Virginia undergraduate. The following day, reports emerged that state Senate Majority Leader Tommy Norment (R) edited a college yearbook filled with racist images; then, on Friday, a second woman accused Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax (D) of sexual assault. He has denied both allegations.

Also late last week and into this week, Gov. Ralph Northam (D) reiterated that he would not be resigning over the blackface scandal that led to a flood of requests for him to exit. He has reemerged in public with high-profile interviews with CBS News and the Washington Post, to mixed reviews at best. That Fairfax is so damaged bolsters Northam’s case for staying in office, although it is the position of many, including top Democrats, that both men need to leave. (This is unlikely to happen as long as the Fairfax situation remains unresolved. This is what saved Northam, far more than any other factor.) Herring, for now, seems safe; that the GOP-controlled state legislature would pick his replacement is part of the reason why: Democrats could figure out a way to keep the governorship and the lieutenant governor’s post in the event of vacancies, but not the attorney general’s office. That said, Herring’s offense objectively seems less serious than Northam’s yearbook photo and his botched explanations for it as well as the disturbing allegations against Fairfax. An attempt by state Delegate Patrick Hope (D) to begin a state legislative impeachment process for Fairfax fizzled Monday.

So here we are, with the top three officials in the state all damaged to at least some degree, but without any real indication as of this writing (Wednesday evening) that any will leave office voluntarily.

What is at stake in the state is more than the future of the three state-level, statewide elected Democrats. Before this cascade of revelations and party chaos, Virginia Democrats were looking at the very real possibility of total state government control and — given that many Southern states were ruled by conservative Democrats before Republican dominance in the region — perhaps the most liberal (or progressive, if you prefer) state government in the post-Reconstruction history of not just Virginia, but the South in general.

The post-Reconstruction political history of the South generally featured conservative white Democrats dominating state governments. But the party’s strength in the South began to weaken for a number of factors, most notably the national Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights following World War II. Change at the presidential level bled down the ballot over the decades, with conservative Republicans gradually building in strength and taking over state legislatures in the South. The completion of that Republican transition in the 11 states of the old Confederacy — the standard definition of the states included in “The South” — only happened from 2010-2012, when the last Democratic state legislative majorities in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and North Carolina all fell to Republicans.

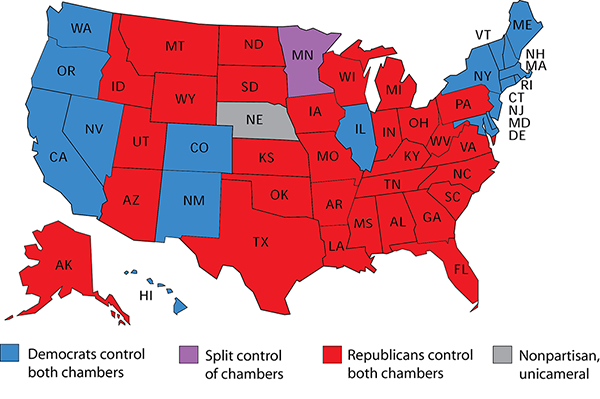

Map 1 shows the current party control of the state legislatures nationally. Note that the Democrats do not control a single state legislative chamber in the South; that’s true even if one defines the South in a broader way by including states like Kentucky and West Virginia, where Democrats have also lost state legislative chambers in recent years.

Map 1: Current party control of state legislative chambers

From a national standpoint, a couple of things stand out.

First of all, only one state has a state legislature where control of each chamber is split, Minnesota. Democrats control the state House and Republicans control the state Senate. The Gopher State did not have state Senate elections last year, which probably was good for Republicans given that Democrats flipped control of the state House. Republicans did pick up a previously Democratic state Senate seat in a special election last week, giving them a narrow 35-32 majority.

The second observation is that control of state legislatures aligns almost perfectly with the 2016 presidential results. Donald Trump won 30 states, and Republicans control every state legislative chamber located in those states. That includes the unicameral Nebraska legislature; while it is technically nonpartisan, Republicans hold a clear majority there, according to Ballotpedia’s count. Meanwhile, Democrats control every chamber in 18 of the 20 states that voted for Hillary Clinton. There are two exceptions: the aforementioned Minnesota Senate and both chambers in Virginia.

In other words, Virginia is an outlier among the states when it comes to state legislative control — it’s the only state where the majority party in both chambers of the state legislature is clearly at odds with its federal partisanship.

Democrats made huge gains in the Virginia state House of Delegates in 2017, netting 15 seats and winning 49 total in the 100-member chamber. They could have forced a 50-50 tie, but Delegate David Yancey (R) prevailed in a drawing to determine the winner of his reelection bid, where the vote ended in an exact tie. As of now, Republicans hold a 51-48 majority in the House of Delegates with a special election coming next Tuesday to fill a vacancy in a heavily Democratic seat (more on that at the end of this piece).

Democrats made their heavy gains in 2017 on a Republican-drawn map that could not stand up to the strain Donald Trump’s presidency put on it. Democrats ended up making their gains almost exclusively in districts that Clinton carried in 2016. These were districts that Republicans either believed would perform better for them in non-presidential years and/or ones whose Democratic trend only emerged later in the decade. The map may very well be unwound in time for the 2019 elections, as a federal court found that the GOP-drawn map was an illegal racial gerrymander, although it’s still possible that the old map could remain. Under the current map, three Republicans would sit in districts Clinton won in 2016; under the new one, seven Republicans would be in Clinton seats, according to Daily Kos Elections. One of them would be Kirk Cox (R), the state House speaker; Yancey, the GOP delegate who won the crucial tied race in 2017, would see his district go from one that Clinton carried with 53% of the two-party presidential vote to one that she would have carried with 59% of the two-party vote, according to calculations by the Princeton Gerrymandering Project. All told, the Virginia Public Access Project analyzed the new districts and found that just one Democratic district would be harder for Democrats to defend under the new map while six would become harder for Republicans to defend. (Thanks to our friend Chaz Nuttycombe and the other sources cited here for helping us sort through the proposed new map.)

The state Senate map, which was a Democratic-drawn map that nonetheless failed to protect the party’s state Senate majority when drawn in advance of the 2011 election, will remain in place regardless of what happens to the House map. Republicans currently hold a 21-19 majority, but they are defending four Clinton-won districts while Democrats don’t hold any Trump-won districts. So the most vulnerable seats appear to be Republican-held ones, most notably an open Northern Virginia district Clinton won with 54% of the two-party vote.

So Democrats need to pick up two seats in each chamber to win outright control of the state legislature. It is reasonable to wonder whether this extraordinary scandal reduces the Democrats’ ability to do so, particularly if the tantalizing (for Democrats) new House of Delegates map falls through. That the three elected statewide state officials, all Democrats, are now compromised complicates the state legislative picture. Democratic candidates would have featured these officeholders at events; now, they probably won’t. Potential Democratic candidates who thought about running may not, or incumbents may decide to retire; Republicans who might not have otherwise run could get off the sidelines (for instance, Randy Minchew, one of the GOP incumbents unseated in 2017, announced a bid to reclaim his old seat last week and cited the “national embarrassment” as a reason why). Northam, Fairfax, and Herring would have raised a significant amount of money for their party’s General Assembly candidates, but surely their ability to perform that essential task has been reduced considerably.

To us, the major Democratic concern isn’t necessarily that a significant slice of Northam voters will defect; instead, it’s that Democrats will be on the wrong end of what even before this scandal broke was an inevitable turnout drop from the most recent election. In the two most recent gubernatorial elections, 2013 and 2017, turnout of registered voters was 43% and 48%, respectively; in the two most recent off-year state legislative elections, 2011 and 2015, it was about 29% each time. Democrats will want that turnout figure to be higher, because it probably would mean that their generally less reliable voter base is coming out in stronger force than it did during the Barack Obama era. The GOP hope, ideally, is to bring some traditional Republican voters in Virginia’s growing suburbs back to the fold after they revolted in favor of Clinton in 2016 and Northam in 2017 or at the very least hope that they won’t show up in the same force as two years ago; that said, the true object of those voters’ ire nine months from now may not be damaged Democrats in Richmond, but rather the president across the Potomac who drove them to defect in the first place.

This is where the nationalization of American politics could bail out the Democrats. Virginia’s voters sometimes seem to take the White House into account when casting their ballots: 10 of the last 11 gubernatorial elections have been won by the party not in the White House. More recently, state legislative districts that seemed Democratic on paper, or at least at the presidential level, backed Republicans while Obama was president. Perceptions of Trump helped unlock these districts for Democrats in 2017. We see this nationalization in other places. For instance, according to polling by Morning Consult, the two least-popular governors in the United States in the leadup to the 2018 election were Oklahoma Republican Mary Fallin and Connecticut Democrat Dan Malloy. Neither were on the ballot that year, but their records arguably were, and the other party tried to make the elections a referendum on the departing incumbents. In neither case did the opposition party succeed: Connecticut followed its federal partisanship and voted Democratic, Oklahoma did the same and voted Republican.

While Virginia is a more competitive state than either Connecticut or Oklahoma, it has been trending Democratic, and feelings about the president could nationalize what otherwise are state-level elections. It’s also worth noting that President Trump’s assertion that Virginia would trend back to the GOP in 2020 because of the Democratic state-level scandals is almost certainly wishful thinking. That’s not to say Trump couldn’t carry Virginia: The state still votes close enough to the national average that if Trump won the national popular vote by several points he could carry Virginia as part of a uniform swing toward him; failing that, though, the state’s trajectory suggests it will vote more Democratic than the nation as a whole in 2020, like it did in both 2012 (by just a hundredth of a percentage point) and 2016 (by more than three points as Sen. Tim Kaine occupied the Democratic vice presidential slot). Virginia voted to the right of the nation in presidential elections for more than a half century prior to 2012. In other words, we think it’s likelier that other states are better candidates to provide the truly decisive votes to whomever wins the presidency in 2020. Trump benefited from his modified GOP coalition, which is very reliant on white voters who do not have a four-year college degree, in a lot of places, particularly in the electorally vital Midwest. But the tradeoff hurt him elsewhere, such as in Virginia, which is more diverse than the Midwest and has higher-than-average levels of four-year college attainment.

No doubt, the Richmond scandal is an immense headache for Democrats, and a black eye for the commonwealth. If Democrats fail in the fall, the scandal probably will be part of the reason why. But it may be that Democrats suffer through agony all year and then win the state legislature in the fall anyway. If that happened, it would be another triumph for the long-term, nationalized trends that have more often animated politics across the country in recent years than the local ones that seem so politically important in the moment they are happening.

P.S. The special election watch continues

Throughout the 2017-2018 cycle, political watchers monitored special elections at the state and federal level for clues about the midterm. Those results were on balance favorable to Democrats, and in some ways did in fact provide a preview of the midterms. Democrats ran on average about 10 points ahead of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 margin in these contests (although of course individual results varied widely). This trend continued in Virginia in December, when Democrats lost a state House of Delegates special election (HD-24) by 19 points in a district Clinton lost by 34.

Prior to the Democratic blowup in Virginia, Democrats won a January state Senate special election in Northern Virginia — SD-33, where the vacancy was caused by Democrat Jennifer Wexton’s election to the U.S. House in November — by about 40 points, eight points better than Clinton’s 32-point victory there in 2016.

The victor in that race, now-state Sen. Jennifer Boysko (D), left behind her very Democratic state House of Delegates seat (HD-86, Clinton +35), which will be filled in a special election next week. The Democratic nominee in that race, Ibraheem Samirah, just apologized for anti-Semitic Facebook posts from his past. While we wouldn’t necessarily draw any broad conclusions from the margin, whatever it is, it’ll be interesting to see if the combination of state government scandal and a controversial candidate causes any significant slippage from the Democratic trend in this district, which a moderate Republican, Tom Rust, held until his retirement just a few years ago in advance of the 2015 election.

Kyle Kondik is a Political Analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia and the Managing Editor of Sabato's Crystal Ball.

See Other Political Commentary by Kyle Kondik.

See Other Political Commentary.

Views expressed in this column are those of the author, not those of Rasmussen Reports. Comments about this content should be directed to the author or syndicate.

Rasmussen Reports is a media company specializing in the collection, publication and distribution of public opinion information.

We conduct public opinion polls on a variety of topics to inform our audience on events in the news and other topics of interest. To ensure editorial control and independence, we pay for the polls ourselves and generate revenue through the sale of subscriptions, sponsorships, and advertising. Nightly polling on politics, business and lifestyle topics provides the content to update the Rasmussen Reports web site many times each day. If it's in the news, it's in our polls. Additionally, the data drives a daily update newsletter and various media outlets across the country.

Some information, including the Rasmussen Reports daily Presidential Tracking Poll and commentaries are available for free to the general public. Subscriptions are available for $4.95 a month or 34.95 a year that provide subscribers with exclusive access to more than 20 stories per week on upcoming elections, consumer confidence, and issues that affect us all. For those who are really into the numbers, Platinum Members can review demographic crosstabs and a full history of our data.

To learn more about our methodology, click here.